Did the ancient Egyptians really marry their siblings and children?

Ramesses II married his daughter and Cleopatra VII married her brother, but how common was marriage within royal and commoner families?

It's often said that ancient Egyptian royalty married within the family, with pharaohs marrying siblings and sometimes even children. But is there any truth to the claim?

The answer is yes: People in ancient Egypt — both royal and nonroyal — married their relatives, but the details vary according to the time period and class.

Among the general population, brother-sister marriages occurred frequently during the time the Romans controlled Egypt — from 30 B.C. to A.D. 395 — but they were rarer in earlier time periods, according to ancient records. Meanwhile, ancient Egyptian royals sometimes married their siblings — a practice that may have reflected religious beliefs — and pharaohs sometimes married their own daughters.

“The question of the practice of incest in Ancient Egypt has given rise to much discussion” among scholars Marcelo Campagno, a researcher with the University of Buenos Aires and the Argentinian National Council of Research (CONICET), told Live Science in an email.

Examples of Egyptian rulers who were married to their siblings include Senwosret I (reigned circa 1961 B.C. to 1917 B.C.), who was married to his sister Neferu; Amenhotep I (reigned circa 1525 B.C. to 1504 B.C.), who was married to his sister Ahmose-Meritamun; and Cleopatra VII (reigned circa 51 B.C. to 30 B.C.), who was married to her brother Ptolemy XIV before he was killed.

Related: What did the ancient Egyptian pyramids look like when they were built?

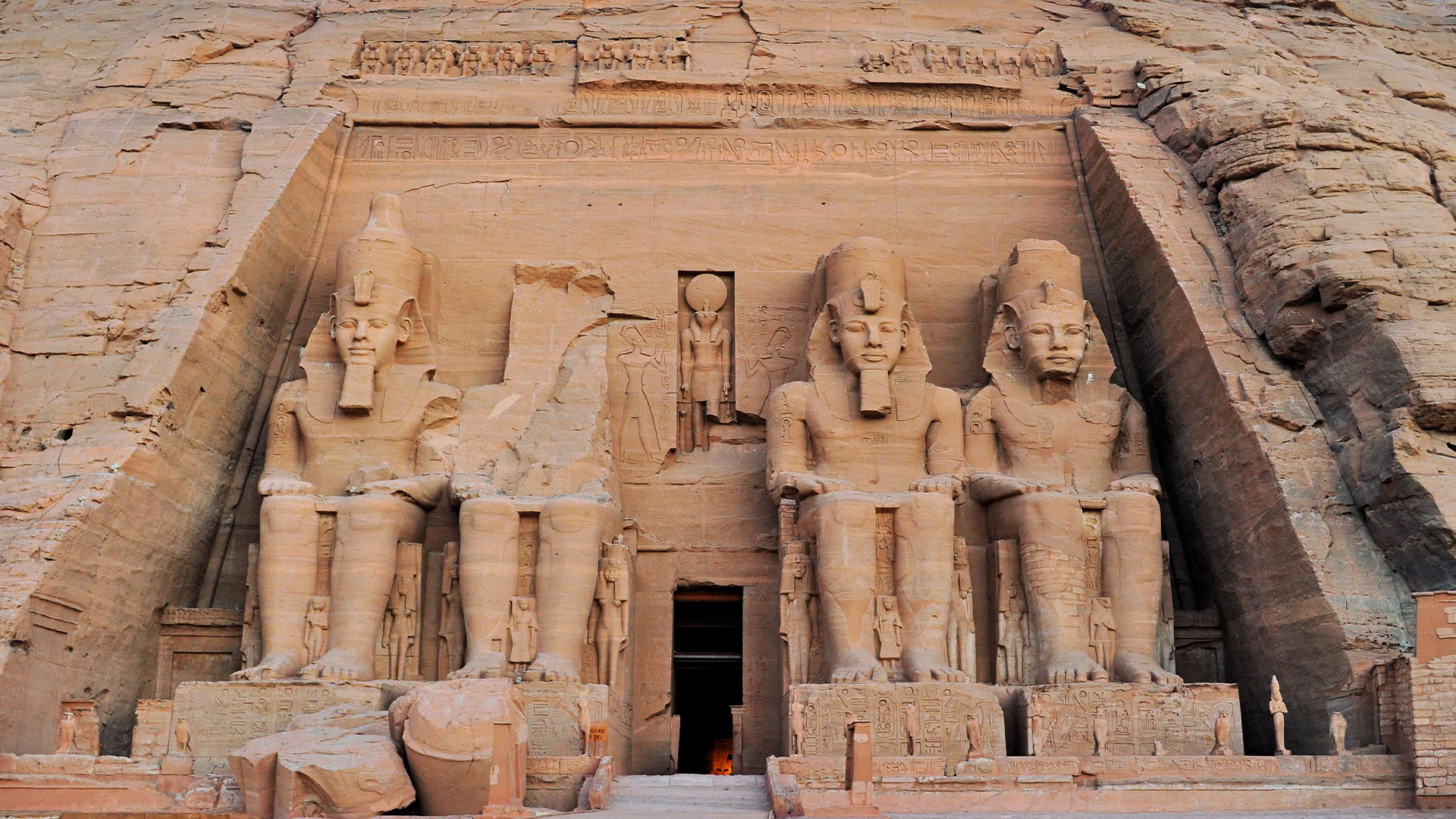

There were also instances of pharaohs marrying their daughters: Ramesses II (reigned circa 1279 B.C. to1213 B.C.) took Meritamen, one of his daughters, as a wife.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Pharaohs in Egypt often had multiple wives and concubines, and incestuous marriages sometimes produced children. Some scholars have suggested that inbreeding contributed to the medical problems of Tutankhamun, a team led by Zahi Hawass, a former Egyptian antiquities minister, and colleagues wrote in a 2010 article published in the journal JAMA.

Brother-sister marriage

Many royal Egyptians entered into brother-sister royal marriages to emulate the practice of Osiris and Isis, two Egyptian deities who were siblings married to each other.

"Osiris was one of the most important gods in Egyptian religion. His consort, Isis, was also his sister according to some ancient Egyptian cosmogonies," Leire Olabarria, a lecturer in Egyptology at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., told Live Science in an email. "Thus, royals engaged in close-kin marriage in order to emulate Osiris and Isis, and perpetuate their images as gods on earth."

Campagno agreed that the Osiris-Isis marriage helps explain why brother-sister marriage was practiced by Egyptian royalty.

Among nonroyals, brother-sister marriage does not appear to have become widespread until the time of Roman rule, when records indicate there were a sizable number of sibling marriages, experts told Live Science.

Olabarria cautioned that it may be difficult to detect brother-sister marriage after the start of the New Kingdom (circa 1550 B.C. to 1070 B.C.) because of changes in how Egyptian words were used. For example, "The term 'snt' is usually translated as 'sister' but in the New Kingdom it started to be used for wife or lover as well," Olabarria said.

Roman rule

Why the number of brother-sister marriages surged during Roman rule is a source of debate. In her book "The Family in Roman Egypt: A Comparative Approach to Intergenerational Solidarity and Conflict" (Cambridge University Press, 2013), Sabine Huebner, a professor of ancient civilizations at the University of Basel in Switzerland, wrote that many of these brother-sister marriages may actually be with a man who was adopted into their wife's family shortly before the marriage. Parents without a son may have wanted this arrangement, as it would have meant that the husband moved into their home rather than their daughter leaving. This would have been important for the financial stability of the parents as they got older, Huebner wrote. This practice of formally adopting a son-in-law occurred in other ancient societies, including Greece.

The adoption of the son-in-law is the best explanation for why brother-sister marriage is attested so frequently in Roman Egypt, Huebner said. "This seems to me the more obvious case than declaring the society of Roman Egypt the only case in human history where full-sibling marriages were celebrated among the common people at large and on a regular basis," she wrote.

Some scholars are not certain that adoption can explain why brother-sister marriage was frequent in Roman Egypt. "The wording of the Egyptian marriage contracts — 'son and daughter of the same mother and the same father' — pretty well rule out adoption in all of those cases," Brent Shaw, a professor emeritus of classics at Princeton University, told Live Science in an email.

There are other possible explanations for why brother-sister marriages frequently occurred in Roman Egypt. One possibility, Olabarria said, is that parents encouraged it so that property and wealth would not be split up as much when they died. Campagno noted that the practice seems to have occurred largely in parts of the population of Greek descent, and Olabarria said brother-sister marriage may have been used as an identity marker of sorts for Egyptians of Greek descent.

Editor's note: Updated at 11:55 a.m. EDT on Aug. 28 to update Marcelo Campagno's title.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.