Did we kill the Neanderthals? New research may finally answer an age-old question.

A complex picture of how Neanderthals died out, and the role that modern humans played in their disappearance, is emerging.

About 37,000 years ago, Neanderthals clustered in small groups in what is now southern Spain. Their lives may have been transformed by the eruption of the Phlegraean Fields in Italy a few thousand years earlier, when the caldera's massive explosion disrupted food chains across the Mediterranean region.

They may have gone about their daily life: Crafting stone tools, eating birds and mushrooms, engraving symbols on rocks, and creating jewelry out of feathers and shells.

They likely never realized they were among the last of their kind.

But the story of their extinction actually begins tens of thousands of years earlier, when the Neanderthals became isolated and dispersed, eventually ending nearly half a million years of successful existence in some of the most forbidding regions of Eurasia.

By 34,000 years ago, our closest relatives had effectively gone extinct. But because modern humans and Neanderthals overlapped in time and space for thousands of years, archaeologists have long wondered whether our species wiped out our closest relatives. This may have occurred directly, such as through violence and warfare, or indirectly, through disease or competition for resources.

Now, researchers are solving the mystery of how the Neanderthals died out — and what role our species played in their demise.

"I think the fact is, we do know what happened to Neanderthals, and it is complex," Shara Bailey, a biological anthropologist at New York University, told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Decades of research has revealed a complex picture: A perfect storm of factors — including competition among Neanderthal groups, inbreeding and, yes, modern humans — helped erase our closest relatives from the planet.

The rise and demise of our closest human relatives

The modern story of Neanderthals began in 1856, when quarry workers found a strange-looking, not-quite-human skull in Germany's Neander Valley.

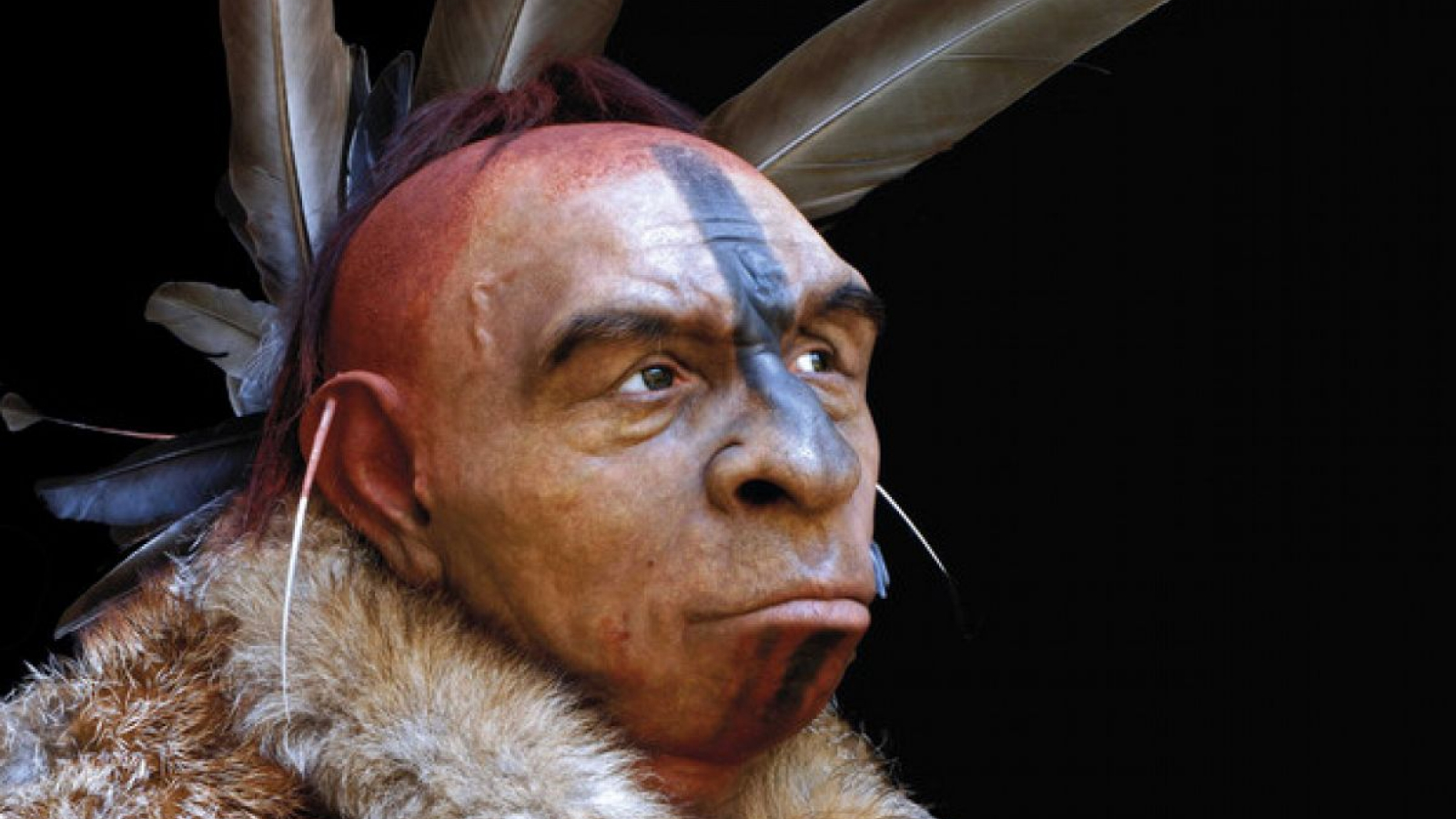

Archaeologists gave the skull a new species name: Homo neanderthalensis. And in the early decades after the discovery, researchers assumed the creatures were knuckle-dragging brutes. This depiction was based on a flawed reconstruction of a skeleton of an old Neanderthal man, whose spine was deformed by arthritis, found at La Chapelle-aux-Saints in France.

Now, more than 150 years of archaeological and genetic evidence makes it clear that these early human relatives were much more advanced than we originally thought. Neanderthals crafted sophisticated tools, may have made art, decorated their bodies, buried their dead, and had advanced communication abilities, albeit a more primitive kind of language than modern humans used. What's more, they survived for hundreds of thousands of years in the hostile climates of Northern Europe and Siberia.

Until they find a frozen Neanderthal and a modern human in a locked embrace, it's always going to be open to interpretation.

Shara Bailey, New York University

Based on archaeological evidence from sites from Russia to the Iberian Peninsula, Neanderthals and modern humans likely overlapped for at least 2,600 years — and perhaps as long as 7,000 years — in Europe. That overlap occurred during a bleak period in Neanderthal history that ended with their downfall — raising the question of whether modern humans were responsible for killing them off.

But the story of Neanderthal life — and extinction — is one of regional variation, said Tom Higham, an archaeological scientist at the University of Vienna.

"In some areas, for example, we see that humans arrive to empty spaces in Europe where there aren't any Neanderthals anymore, seemingly," Higham told Live Science. "And in other places, we see that there's probably an overlap that happens … we know that people are interbreeding."

The first empirical proof of that interbreeding was found in 2010, when a Neanderthal genome was sequenced. Since then, genetic analysis has shown that Neanderthals and modern humans shared much more than a geographic area — we regularly exchanged DNA back and forth, meaning there is a bit of Neanderthal in every modern human population studied to date.

Related: 'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors

Already on the brink

When modern humans and Neanderthals met tens of thousands of years ago, the latter were probably already in trouble. Genetic studies suggest that Neanderthals had lower genetic diversity and smaller group sizes than modern humans, hinting at a potential reason for Neanderthals' demise.

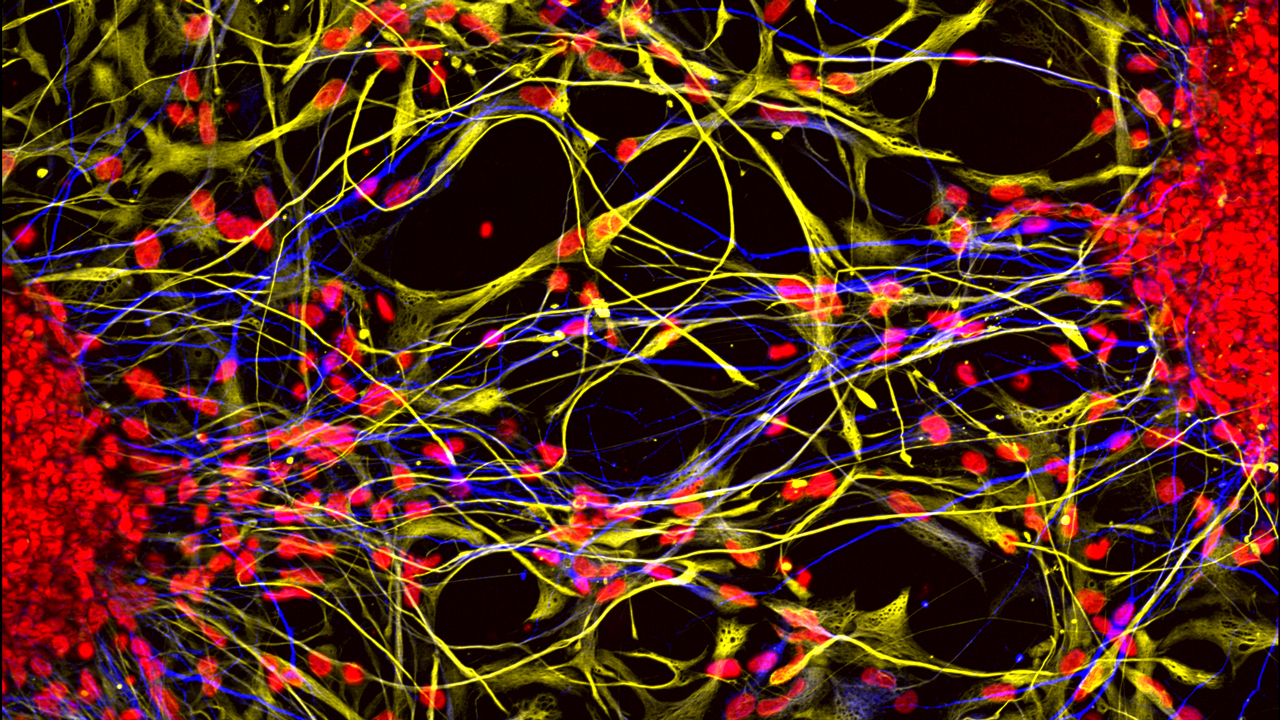

"Genetically, one big clue that we get is this idea of heterozygosity," Omer Gokcumen, an evolutionary genomicist at the University at Buffalo, told Live Science. An individual receives two copies, or alleles, of a gene from each parent. Individuals are "heterozygous" for a given gene if they inherit a different allele from each parent. In Neanderthals' small communities, which contained fewer than 20 adults in each group, more inbreeding occurred. That meant fewer of them inherited different versions of a gene from each parent and, therefore, had low heterozygosity.

"Neanderthals may have suffered for that — what they call a mutational burden," Gokcumen said. Genetic research suggests Neanderthals had many problematic mutations that likely affected their survival. "Because of their small population size, they couldn't actually breed these bad alleles out, and their kids may actually be sickly at the end," Gokcumen said.

Any population of animals survives into the future through successful reproduction and rearing of offspring. Researchers estimating the mortality rates of Neanderthal infants have found that a decrease of even 1.5% in the survivorship of these children could result in population extinction within 2,000 years, April Nowell, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, told Live Science.

"There doesn't have to be very much going on to really have a dramatic impact on the viability of your population," Nowell said.

So while Neanderthal populations began decreasing until they became small, isolated groups without the social support necessary to care for their increasingly sickly babies, modern human groups quickly expanded through Europe.

Humans and Neanderthals: A bad mix?

During two periods across Eurasia 135,000 and 100,000 years ago, Neanderthal populations nearly died out. But they bounced back, powering through these cold snaps and the resulting changes to their landscapes.

"Neanderthals survived all of these hardships," Bailey said. "It wasn't until they had the additional pressure of Homo sapiens that they eventually went extinct."

Given the overlap in time and space, researchers used to think modern humans played a direct role in Neanderthals' demise via warfare or novel diseases.

There is some evidence of violence on Neanderthal skeletons. A young adult male from St. Césaire, France, dating to 36,000 years ago suffered a fracture to the top of his head made with a sharp implement, and an older male found in Shanidar Cave, Iraq, dating to around 50,000 years ago had a partially healed stab wound on his left rib. But there's no way to say whether modern humans or other Neanderthals inflicted this violence. Unless archaeologists find a site where Neanderthals are clearly the victims of a massacre inflicted by modern humans, it will be impossible to conclude that modern-human violence was a major cause of Neanderthals' extinction.

Nor is there genetic evidence that modern humans' diseases killed off the Neanderthals, though we do share many immune-related genes. For instance, we inherited Neanderthal genes that make us susceptible to autoimmune disorders such as lupus and Crohn's disease as well as to severe COVID-19. Future genetic analyses may reveal the potential role of disease in Neanderthals' demise, Gokcumen said.

Winners and losers in the fight for resources

But warfare and pestilence aren't the only possible ways modern humans may have led to Neanderthals' vanishing. When two groups come together, competition can lead to tragic outcomes.

Neanderthal artifacts, such as pendants and etchings, show that Neanderthals were intelligent. But new research suggests there are significant differences between H. sapiens and Neanderthal brains: Modern humans have more neurons in brain regions key to higher-level thinking, and their neurons are more connected — meaning modern humans were likely more capable of thinking quickly. Combined with Neanderthals' greater difficulty in processing language, this could mean modern humans had an advantage in key tasks, Nowell said, such as hunting and foraging for food.

And while Neanderthals' extremely isolated groups may have had a biological disadvantage, they probably had a cultural one, too.

"Ideas can spread more easily when you have bigger populations and other people can build on them," Bailey said. But given Neanderthals' disparate populations, "their artistic or cultural kinds of innovations might not have progressed the way we see in much larger populations that have a lot of interactions with people," she said.

Although Neanderthals created tools that were very sophisticated for the time, we haven't found any unambiguous long-range weapons made by Neanderthals. Modern humans' ability to devise projectile weapons, by contrast, may have given us a survival advantage.

Related: Could Neanderthals talk?

But the full implications of these differences on Neanderthals' survival aren't yet known.

"We could also think about intergroup competition or competition between groups of Neanderthals," Nowell suggested, as a potential result of their dwindling numbers and modern humans' encroachment.

When looking at contemporary and historical hunter-gatherer groups, Nowell and co-author Melanie Chang, a paleoanthropologist at Portland State University, noticed that these groups often tightly regulate who has been able to use the land and its resources, and that being part of the "in group" can be a matter of survival. As Neanderthals began to disappear from most of Eurasia and retreat to southern Iberia, competition among Neanderthal groups would have risen.

"Maybe it's competition with other Neanderthals that prompts them to start differentiating themselves more," Nowell said.

That seems particularly persuasive, given that around 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, there was a cultural explosion among both modern human and Neanderthal groups. These cultural elements included a surge in personal adornment, such as painted shells, probably worn as pendants, that could have served as "group" symbols, Nowell said.

No cohesive, shared fate

Given the mounting evidence that Neanderthals and modern humans interacted regularly for thousands of years, many researchers are looking to an unusual place for the answer to what happened to Neanderthals: a theory first put forward by paleoanthropologist Fred Smith and colleagues 35 years ago.

"He came up with this suggestion that there was gene flow and a slow assimilation of Neanderthals into human populations," Higham said.

In essence, the two groups simply got used to hanging out with one another, and as more and more humans moved into Eurasia, eventually their larger population swamped the Neanderthals, whose lineage petered out. This idea is supported by a study that found H. sapiens simply absorbed the Neanderthals into our population. In that way, we may have made Neanderthals vanish as a distinct group — by making some of the remaining ones part of our family.

But this theory currently lacks "smoking gun" evidence of humans and Neanderthals living together for extended periods at the same site. They were sharing genes, but the archaeological evidence does not show Neanderthals and modern humans sharing either a home or the close social ties necessary to say we assimilated Neanderthals into our own population.

"Until they find a frozen Neanderthal and a modern human in a locked embrace, it's always going to be open to interpretation," Bailey said.

Even if we do find such a site, it is unlikely to change the nuanced, complicated picture of Neanderthals during their last moments.

"Some Neanderthal populations died out, some got massacred, some interacted and some only exchanged ideas," Sang-Hee Lee, a biological anthropologist at the University of California, Riverside, told Live Science. "The really exciting questions like 'Why did Neanderthals disappear?' 'Why did they go extinct?' no longer can have one overarching theory" she said. "Neanderthals as a whole did not have a cohesive, shared fate."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.