Elite Bronze Age tombs laden with gold and precious stones are 'among the richest ever found in the Mediterranean'

The obvious wealth of the tombs was based on the local production of copper, which was in great demand at the time to make bronze.

Hundreds of ancient artifacts, including headbands of pure gold, have been unearthed from elite Bronze Age tombs on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

The finds show the great wealth of the people buried there, which was based on the island's trade in copper — a crucial metal at that time that was used to make bronze.

The artifacts include many imported into Cyprus from other major cultures in the region, including the Minoans on Crete, the Mycenaeans in Greece and the ancient Egyptians.

Archaeologist Peter Fischer, professor emeritus at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, said the imported objects confirmed the extent of Mediterranean trade during the Late Bronze Age, between about 1640 B.C. and 1050 B.C.

"The numerous finds of gold, most likely imported from Egypt but showing mainly Minoan motifs, demonstrate that the Egyptians received copper in exchange," he told Live Science.

Related: Gold 'lotus flower' pendant from Queen Nefertiti's time discovered in Cyprus

The archaeologists also found everyday items, such as fishbones from freshwater Nile perch. "They came either with Egyptian ships or with returning Cypriot crews, demonstrating the intense trade between these cultures," Fischer said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rich in copper

Fischer and his colleagues have been excavating a Bronze Age trading emporium at Hala Sultan Tekke on the southern coast of Cyprus since 2010; and they discovered the elite tombs earlier this year.

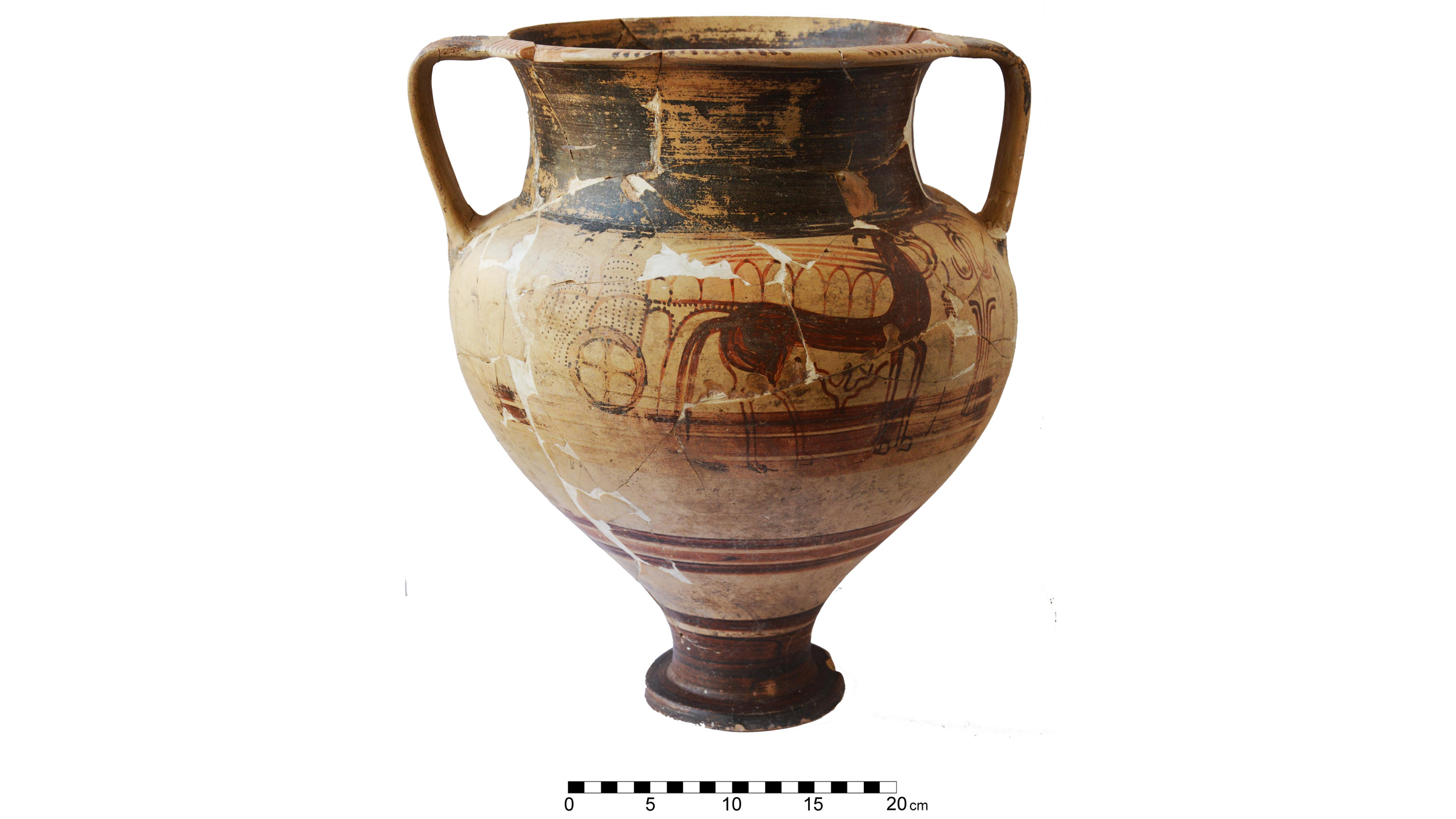

The two tombs were filled with more than 500 artifacts, including pottery from Crete, Greece and Sardinia; ornaments made of amber from the Baltic; precious stones like blue lapis lazuli from Afghanistan and red carnelian from India; bronze mirrors; and daggers, knives and spearheads.

Several items were made from ivory and a distinctive glazed ceramic called faience, which had been brought there from ancient Egypt, according to a statement from the University of Gothenburg.

Among the most remarkable artifacts are gold diadems, which are embossed with images of bulls, gazelles, lions and flowers.

While they seem to be Minoan in style, the diadems were probably crafted in Egypt during the 18th dynasty, between about 1550 B.C. and 1295 B.C. — and perhaps at the time of the Pharaoh Akhenaten and Nefertiti, according to the statement.

Fischer said the wealth of the island's elites was based on their control of copper ore mines in the Troodos Mountains, in the west of Cyprus. Copper was alloyed with tin to make bronze, so it was in great demand.

The tombs "rank among the richest ever found in the Mediterranean region," Fischer said in an email. "The precious tomb artefacts indicate that their occupants ruled the city, which was a centre for the copper trade in the period between 1500 and 1300 BCE." At that time, "Cyprus was a 'crucible' of cultures, most likely dominating the trade in the eastern Mediterranean," he said.

Family tombs

The researchers discovered the elite tombs just outside the vast ancient city at Hala Sultan Tekke using magnetometers, which measure the geomagnetic field to reveal where earth underground has been disturbed in the past.

Each tomb had several chambers connected to the surface by a narrow passage; and they contained the remains of several people, including those of a woman buried beside a 1-year-old child.

It's possible that the tombs were royal, but little is known of the form of government on Cyprus at that time, Fischer said. "The tombs are obviously family tombs… keeping the family together in the afterlife."

Fischer said the researchers will use DNA analysis in an effort to determine how the people buried in the tombs were related, while analysis of the ratios of different isotopes (nuclear forms) of strontium in the bones might shed light on their geographical origins.

"We have preliminary results which confirm the multiculturality of the inhabitants of Hala Sultan Tekke," he said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.