Even Stone Age people burned their porridge, 5,000-year-old food-scorched clay pot reveals

Thousands of years ago, a Neolithic person tried cooking porridge but ended up burning it.

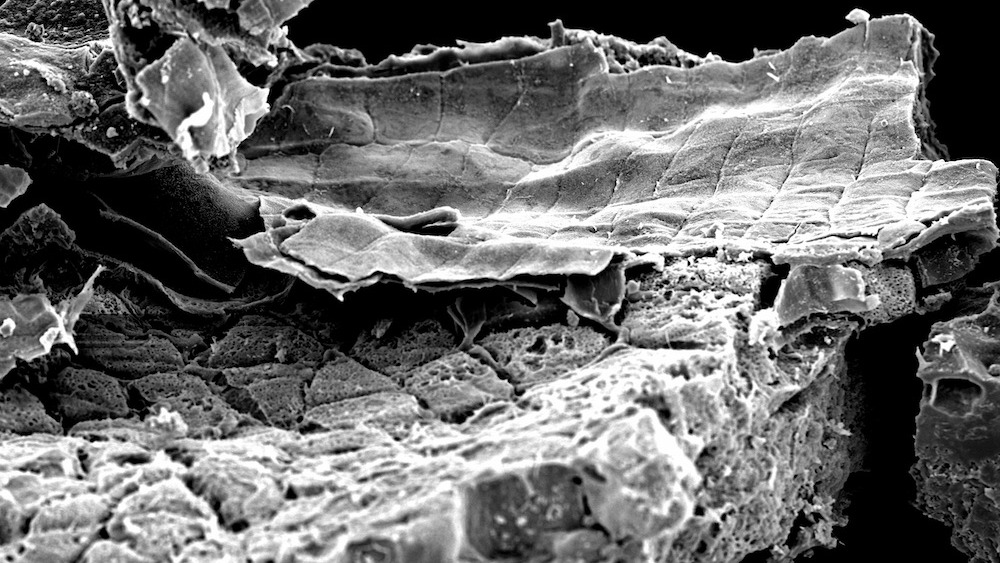

People have been burning their porridge for at least 5,000 years, remains of a charred cooking pot unearthed in Germany confirms. And just like today, cleaning the pot was more hassle than it was worth.

Archaeologists discovered the meal mishap after examining a trash heap of mixed pottery shards at Oldenburg LA 7, a Neolithic settlement that researchers consider one of the oldest villages in Germany, according to a study published Jan. 19 in the journal PLOS One.

"As soon as we looked inside the person's cooking pot it was obvious that something went wrong," study lead author and archaeobotanist Lucy Kubiak-Martens, a cooperation partner with BIAX Consult, a company that specializes in archaeobotany and paleobotany in the Netherlands, told Live Science.

Chemical analyses of the residues still caked onto the ceramic shards revealed "food crusts" containing traces of different ancient cereal grains, including emmer wheat and barley. Researchers also found remnants of white goosefoot, a wild plant known for its starchy seeds, according to a statement from Kiel University in Germany.

Related: Largest-ever genetic family tree reconstructed for Neolithic people in France using ancient DNA

"One pottery shard that once was part of a plain, thick-walled pot contained the remains of white goosefoot seeds, which are related to quinoa and rich in protein," Kubiak-Martens said. "There was also emmer, which when sprouted, has a sweet flavor. It looked like someone had mixed cereal grains with the protein-rich seeds and cooked it with water. It wasn't incidental, it was a choice."

While there is evidence that people ground wild oats, likely for flour, 32,000 years ago in Italy, the newly described broken pot may represent the world's first recorded (and failed) attempt at cooking porridge. It is impossible to say if the person broke the pot rather than be bothered with cleaning it, or if the pot broke naturally long after the cooking mishap.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A separate pottery shard contained animal fat residue — most likely milk — that had seeped into the clay. However, it didn't appear that the cook in question had mixed any grains into the liquid, so the milk was unlikely part of the porridge.

"The sprouted grains also tell us when they harvested them, which would have been when they sprouted sometime in the late summer," Kubiak-Martens said. "Back then they couldn't put grains on a shelf and store them for later use like we do today. They had to use what they harvested immediately."

While previous analyses of soil samples have shown evidence of cooking with similar ancient grains and seeds during this time period, this study marks the first time that researchers have found burnt food residue on a ceramic vessel in Neolithic Germany and offers a glimpse of this person’s diet, according to the statement.

"[This cooking incident] not only shows us the last step in someone's daily routine of preparing meals but also the last cooking event using this pot," she said. "This is much more than just a charred grain. We are seeing how people prepared their daily meals thousands of years ago."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.