Extremely rare Denisovan jawbone confirms human cousins spread across Asia

Researchers have determined that a mysterious jawbone discovered on the seafloor off the coast of Taiwan was Denisovan, proving that the archaic humans were distributed widely over Asia.

A mysterious human jaw discovered off the coast of Taiwan doesn't belong to our species or Neanderthals, but to another extinct relative, Denisovans.

In a new study, researchers used a cutting-edge technique that analyzes proteins to determine which species the jawbone belonged to, which had been a mystery since its discovery in the early 2000s off the west coast of Taiwan. Their approach showed that the individual was Denisovan, a "cousin" of Neanderthals and humans that roamed throughout Asia during the Pleistocene epoch, and it opens the door to identification of unknown human fossils.

"The same technique can and is being used to study other hominin fossils to determine whether they too are Denisovans, Neanderthals or other hominin populations," study co-author Frido Welker, a molecular anthropologist at the University of Copenhagen, told Live Science.

Welker and an international team of experts wanted to better understand the Penghu 1 jawbone, a specimen that was netted by a fisherman from the floor of the Penghu Channel, roughly 15.5 miles (25 kilometers) off the west coast of Taiwan. In the decade since Penghu 1 was documented, paleoanthropologists have disagreed on whether the robust jaw with large teeth came from a Homo erectus, an archaic Homo sapiens, or a Denisovan.

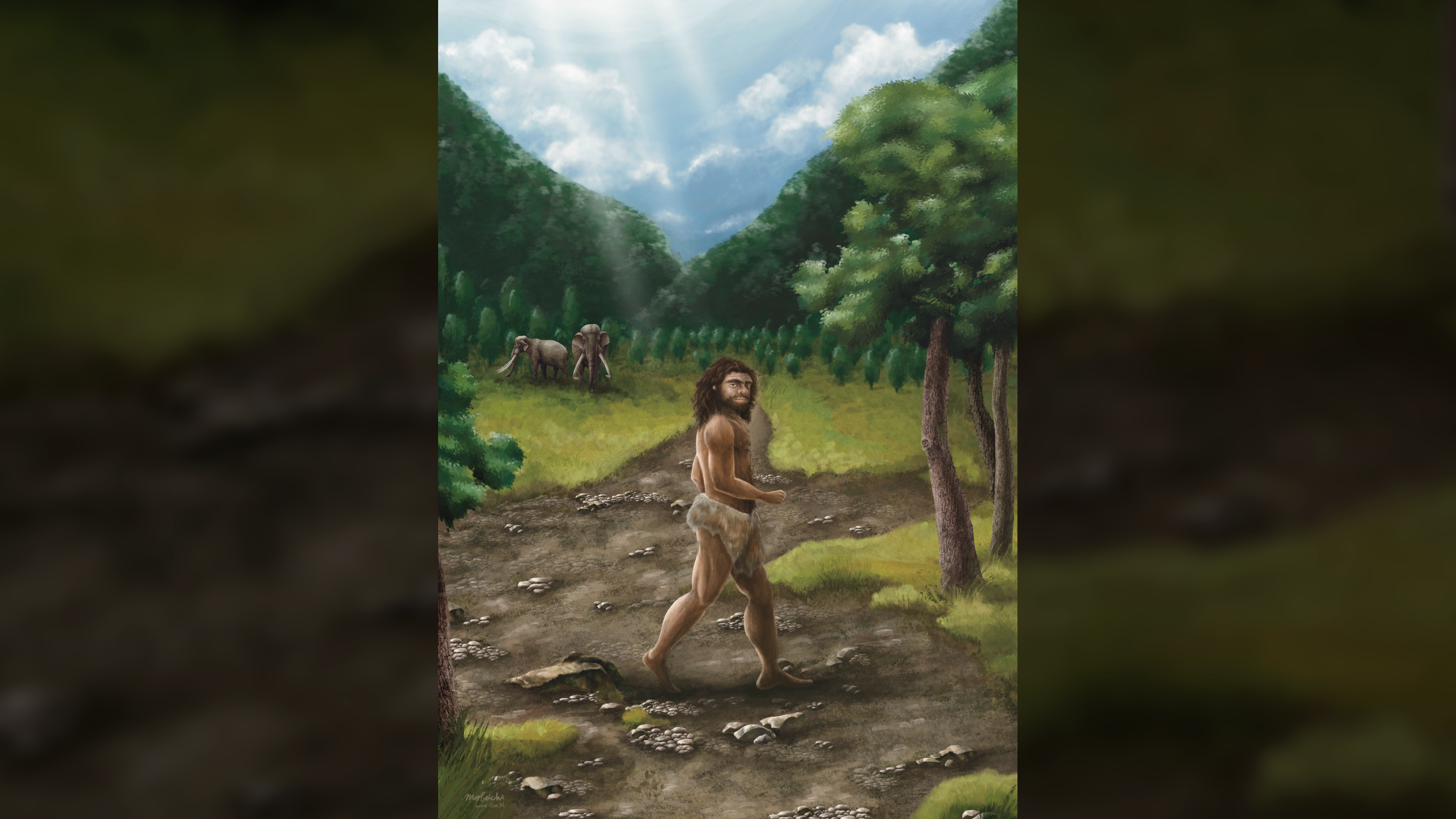

Denisovans are extinct human relatives who lived at the same time as Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. But unlike Neanderthals, whose bones have been found throughout Europe and western Asia for more than a century, Denisovans are mostly known from DNA, since only a handful of fossils have ever been found, most of which come from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Without a large collection of fossils, it is difficult for experts to identify new Denisovan skeletons and to figure out where they lived and how they’re related to humans.

Using the relatively new technique of paleoproteomics, or the analysis of ancient proteins, the research team showed that Penghu 1 was male and that his particular suite of amino acids and proteins was most similar to Denisovans. They published their findings April 10 in the journal Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It wasn't possible to make real meaning of this specimen even 8 or 9 years ago," Sheela Athreya, a biological anthropologist at Texas A&M University who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. "This study confirms what we always inferred — that there has been hominin presence in the farthest extent of eastern Eurasia throughout the Pleistocene."

Dating conundrum

One limitation to the new study, however, is that Penghu 1 can’t be dated confidently using traditional methods such as carbon-14 or uranium dating because the specimen was waterlogged for so long, and DNA extraction attempts also failed.

Animal bones found with the jawbone suggest two age ranges, Welker said — either 10,000 to 70,000 years ago or 130,000 to 190,000 years ago. "If the specimen falls into the younger age range, it could potentially be the youngest Denisovan found to date," he added. Currently, the youngest Denisovan fossil is 40,000 years old and was found on the Tibetan Plateau.

But even with the uncertainty in exact dates, the identification of Penghu 1 as a Denisovan shows that these groups were widely distributed throughout Asia, from frigid regions like Siberia to warm and humid areas like Taiwan.

"It is now clear that two contrasting hominin groups – small-toothed Neanderthals with tall but gracile mandibles and large-toothed Denisovans with low but robust mandibles," the researchers wrote in the study, "coexisted during the late Middle to early Late Pleistocene of Eurasia."

This conclusion shines a light on the diversity and evolution of Homo, and the researchers’ next steps will be to use paleoproteomics to identify more archaic bones from the genus.

"The meaningful result of this work is that we can do so much more with previously unprovenienced fossils found in channels and riverbeds in Asia," Athreya said. "That's exciting!"

Neanderthal quiz: How much do you know about our closest relatives?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.