Famous Neanderthal 'flower burial' debunked because pollen was left by burrowing bees

A new study debunks the idea that Neanderthals buried a man on a bed of flowers about 75,000 years ago.

Scientists are blaming an unsuspecting creature for disturbing a 75,000-year-old Neanderthal burial: burrowing bees. These insects may have hidden pollen underneath a Neanderthal's remains, tricking researchers into thinking the Neanderthal had been buried on top of a bed of flowers, a new study finds.

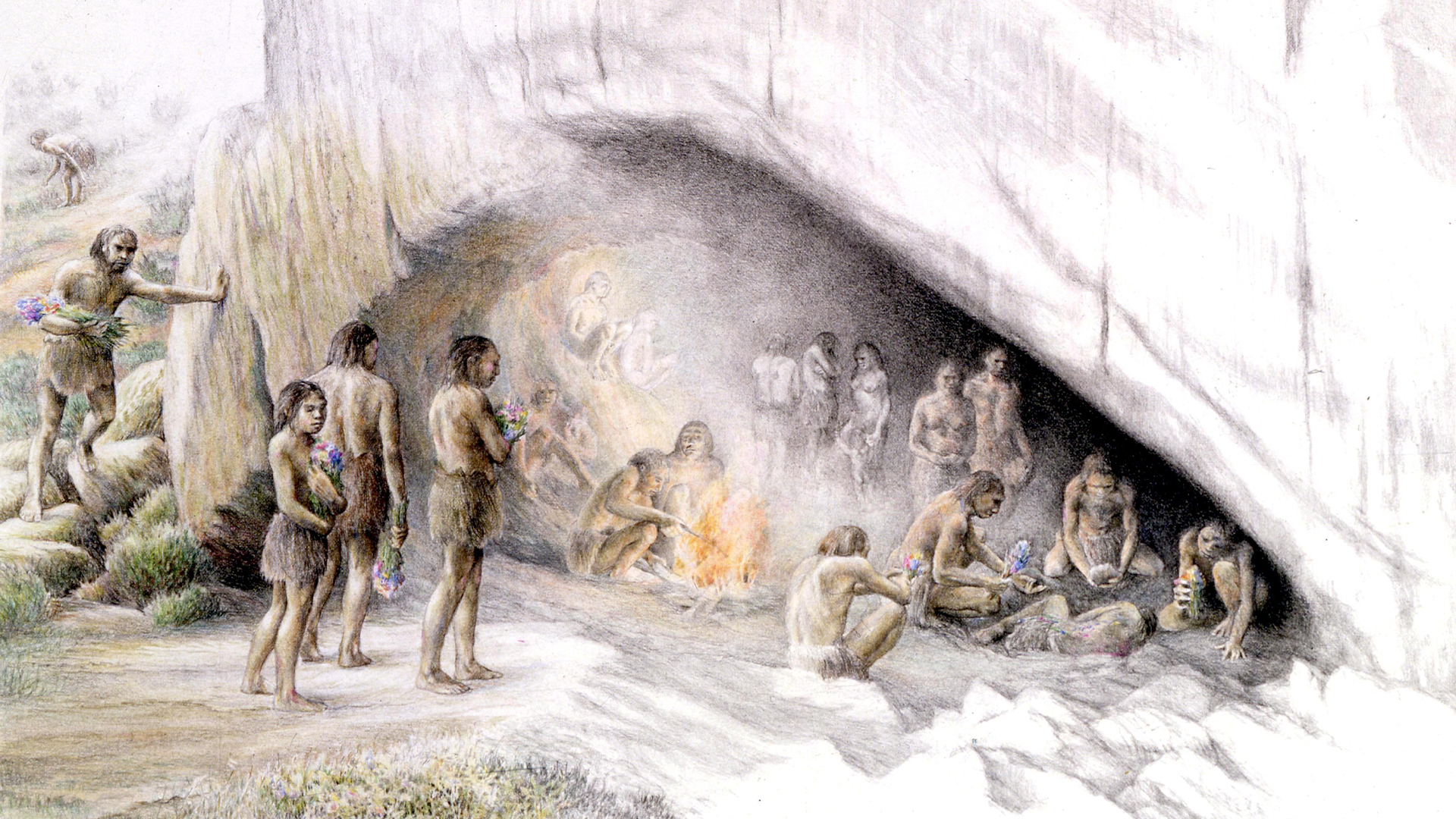

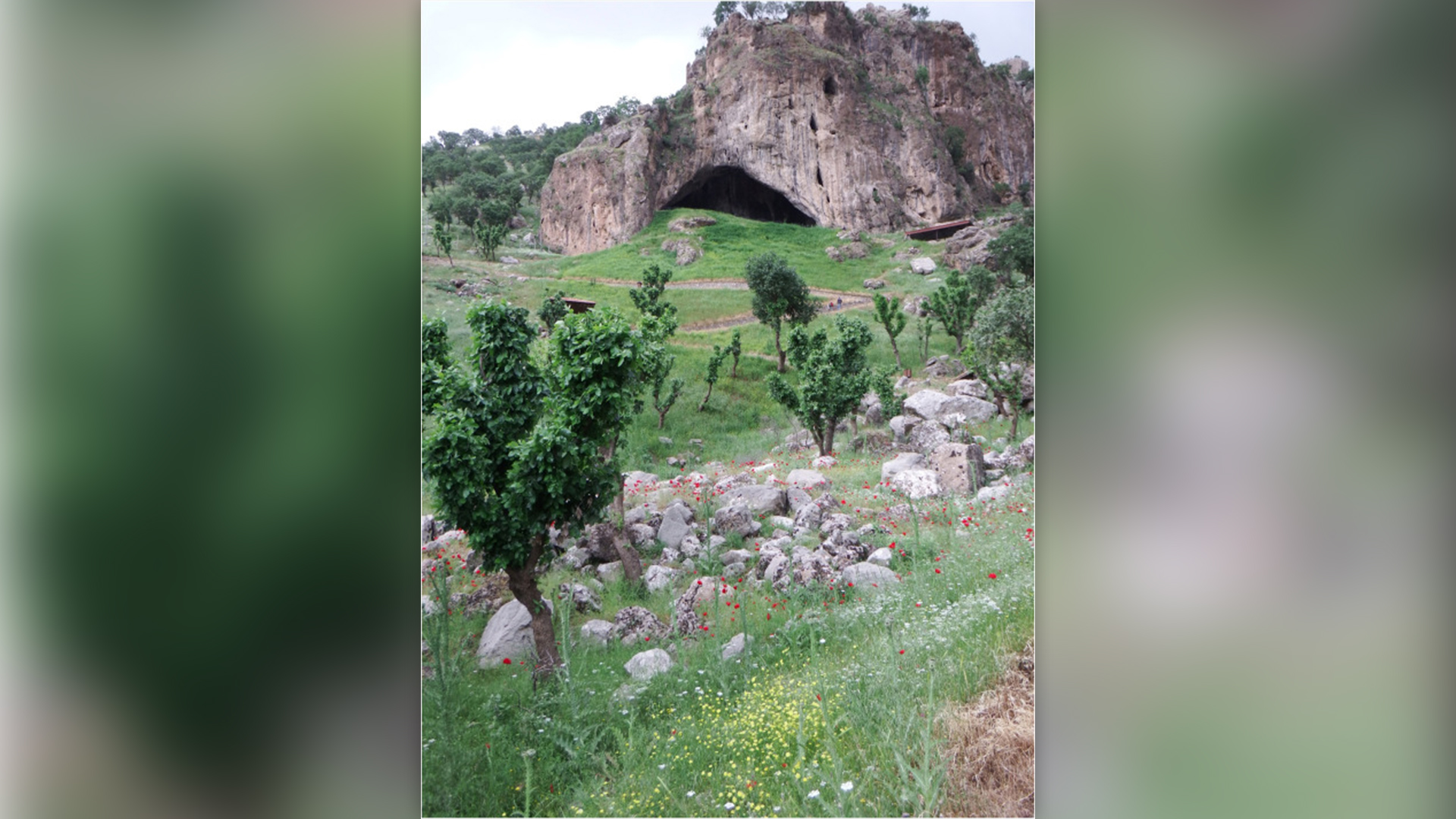

The flower burial interpretation blossomed over half a century ago, when researchers found the site of Shanidar, a rocky cave in the Zagros Mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan that held several Neanderthal burials. One of these, which scientists called Shanidar 4, became known as the "flower burial" when researchers discovered clumps of pollen from flowering plants in the soil underneath an adult male Neanderthal.

The burials at Shanidar, initially excavated in the 1950s and 1960s, were the first evidence that Neanderthals, cousins on our evolutionary tree, engaged in ritual depositing of dead bodies.

Although evidence of Neanderthal burial is no longer controversial in the field of archaeology, the interpretation of pollen as evidence of a flower-adorned burial ritual is still debated.

In the new study, published Aug. 28 in the Journal of Archaeological Science, a team of researchers led by Chris Hunt, a paleoecologist at Liverpool John Moores University in the U.K., reexamined the pollen evidence from Shanidar 4 and found that burrowing bees were a better explanation for the pollen than a Neanderthal funeral ritual.

Related: How smart were Neanderthals?

Soil samples from on top of and underneath the burial were originally studied in 1975 by two palynologists — pollen experts — who determined they came from five known and two unidentified taxa, or biological groups. They suggested that all of these plants were available to be picked at the same time, likely between late May and early June.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While Hunt and his team largely agree with the earlier identification of the plant species, they discovered that the plants actually grow at slightly different times of the year, calling into question the previous interpretation that Neanderthals gathered flowers to bestow on the dead.

During excavations by Hunt and his team in 2016, they noticed a potential alternative explanation for the pollen: ancient mud-lined bee burrows close to Shanidar 4. These ground-nesting bees could have drilled into the dirt and deposited collected pollen as they moved through the burrows.

The mixed clumps of pollen aren't indicative of entire flowers being laid down, the researchers wrote in their article. Instead, they suggest that it is far more likely that "pollen was collected and deposited in clumps by bees."

Hunt and his team think the pollen is likely ancient, perhaps even closely contemporaneous with the Neanderthal burial. But neither the pollen nor the bees can be directly dated.

"There have been successful experiments directly dating pollen grains," Hunt told Live Science in an email. But bee exoskeletons are not easy to radiocarbon-date, and "the level of Shanidar 4 is older than radiocarbon will extend, at about 75,000 years." (Radiocarbon dating can reliably date organic items up to 50,000 years old.)

Angie Perrotti, a palynologist who runs the Palynology and Environmental Archaeology Research Lab (PEARL) who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that Hunt and colleagues made a "compelling argument" for pollen introduction through burrowing bees. "This case underscores the crucial role of precise sampling and systematic archiving of sediment and pollen samples to allow for the reproducibility of prior research," she said.

While Hunt and colleagues' work has not substantiated the flower part of the "flower burial," they affirm that the tight cluster of burials at Shanidar remains incredibly significant to our understanding of Neanderthals and noted that "woody tissue" samples collected from the site may hold the key to learning more about their burial rituals.

"I favour the idea that the Neanderthals put branches and other vegetation over the bodies," Hunt said. Placing the spiky species Centaurea solstitialis (yellow star-thistle) on top of, rather than under, the deceased Neanderthals could have defended the bodies from scavengers. "But the evidence is pretty equivocal, and I'm still working on the contexts," Hunt said. "So watch this space..."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.