'Hairy books' bound by medieval monks are covered in sealskin, study finds

A scientific analysis of dozens of 12th- and 13th-century books found in European monasteries reveals they were bound in sealskins procured by Norse traders from as far away as Greenland.

In medieval Europe, some handcrafted books were bound with skin from an unexpected source: seals.

A new analysis of ancient DNA found in medieval books from European abbeys reveals that these seals came from the northwestern Atlantic Ocean, where they were hunted in the 12th and 13th centuries for their skins. The sealskins were then traded by the Norse descendants of the Vikings before ending up as book covers.

In the study, published Wednesday (April 9) in the journal Royal Society Open Science, a team of researchers subjected 32 medieval books to biocodicological analyses — a series of methods aimed at revealing biological information preserved in codex-style books.

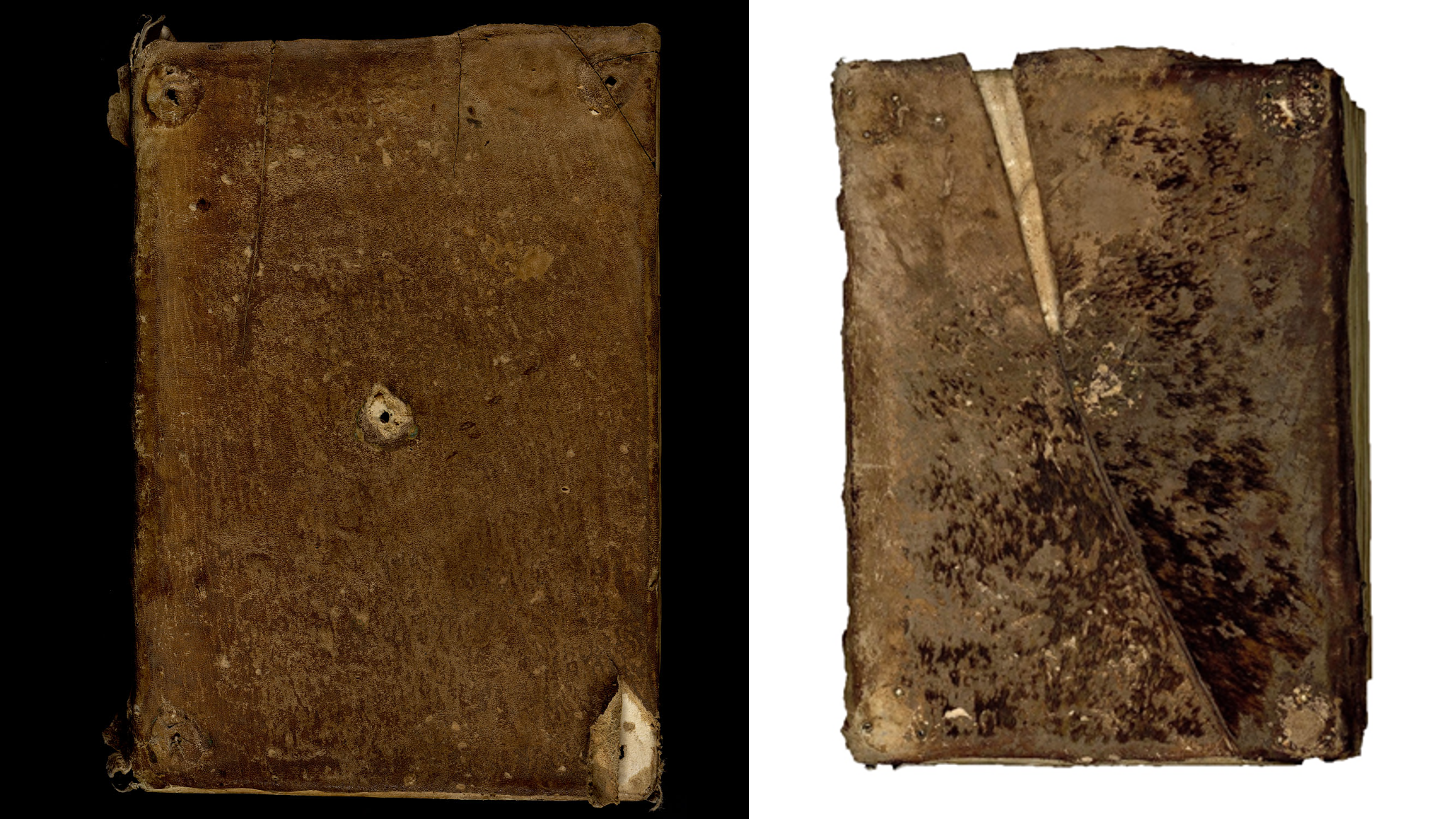

Medieval codices were written on pieces of parchment made of animal skin, that were bound together with wood, leather, cord or thread. Some also had a second protective cover, called a chemise, which was often made from boar or deer skin.

But the new study revealed that some chemises were actually made from seals instead.

The researchers began their investigation at the Library of Clairvaux Abbey in Champagne, France, which holds 1,450 medieval books produced by scribes at this Cistercian abbey, part of a Catholic religious order. Focusing on 19 books created between 1140 and 1275, the experts used mass spectrometry, a technique that can reveal the chemical makeup of an object, and ancient DNA analysis to reveal that they were all bound with skin from pinnipeds, a group that includes seals.

Related: People in Scandinavia may have used boats made of animal skins to hunt and trade 5,000 years ago

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers identified an additional 13 "hairy books" from "daughter abbeys" in France, England and Belgium dated to between 1150 and 1250 that were also bound in sealskin.

The ancient DNA analysis helped the researchers narrow down which pinniped species eight of the skins came from, pinpointing harbor, harp and bearded seals. Additionally, they were able to tell that the seals came from a surprisingly diverse geographic area, including Scandinavia, Denmark, Scotland and either Greenland or Iceland.

"The skins were either obtained through trade or as part of the church tithe," study lead author Élodie Lévêque, an expert in book conservation at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University, told Live Science in an email. "It is doubtful," she said, that these bindings "would have existed without the availability of sealskins from Norse sources."

All of the sealskin books were made in abbeys located along known 13th-century European trading routes, the researchers noted in their study; these were also Norse trading routes. In particular, the Norse traded walrus ivory and furs from Greenland to mainland Europe, and historical records suggest they used sealskins to pay tithes to the Catholic church in the 13th century.

"The Cistercians had a particular preference for white and discreet forms of luxury, which aligns well with the aesthetic qualities of sealskin," Lévêque said. Another well-known sect, the Benedictines, favored darker hues.

However, the monks may not have known that their prized book-binding skins were actually from seals, she said, since there was no term for the animal in the French language at the time.

The widespread use of sealskins in medieval libraries has challenged previous assumptions about which species were used to bind books, the researchers wrote in their study. It has also revealed that the trade network between the Norse in Greenland and abbeys in France was extensive and robust.

But there is no obvious correlation between the actual contents of the books and the use of sealskin covers, and no written explanation for the use of sealskins in book-binding survives, the researchers noted in their study.

"The distinctive white, furry bindings may therefore have been appreciated solely for their visual and environmental qualities – they're waterproof – rather than for any knowledge of their zoological and geographical origin," Lévêque said.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.