Head lice invaded the Americas alongside the 1st humans

A genetic analysis of head lice that have evolved in tandem with humans has revealed two distinct groups of lice that merged in the Americas as a result of Asian and European migrations.

Blood-sucking head lice have evolved alongside their human hosts so closely that their genes mirror waves of human migration into the Americas, a new study has found.

A genetic analysis of human lice (Pediculus humanus) from across the globe revealed a clear split between lice originating from Asia and those from Europe. In the Americas however, hybrids of Asian and European lice populate North and South America, while lice that first evolved in Asia dominate in Central America.

This genetic mishmash raised questions about the influence of human migrations on the evolution of our oldest and most loyal parasites.

"Head lice have been with humans for the last two million years," study co-author Ariel Ceferino Toloza, an entomologist and head lice ecologist at the Pest and Insecticide Research Center in Argentina, told Live Science. "When humans move, they also carry this ectoparasite."

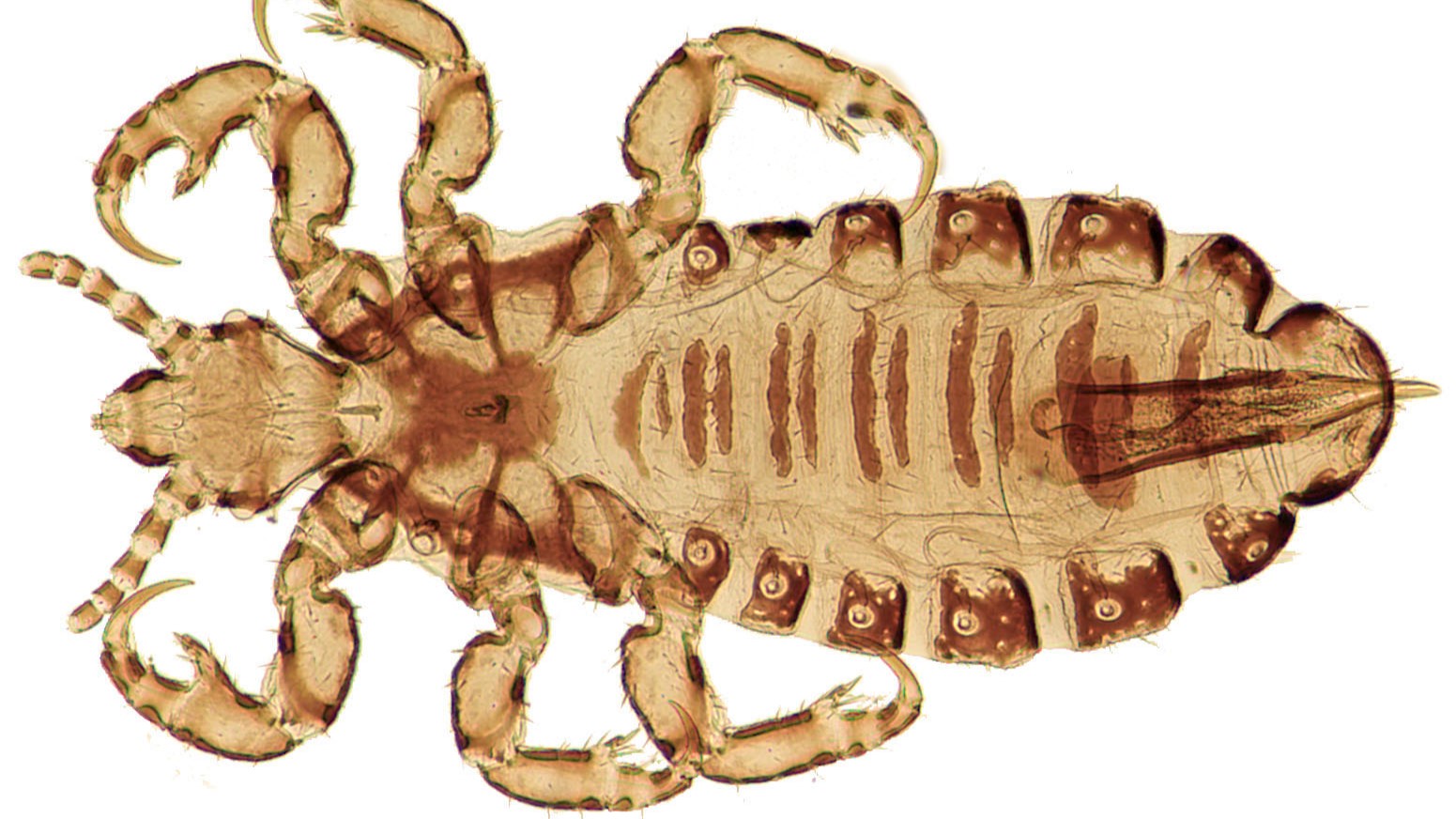

Head lice (P. humanus capitis) are a subspecies of human lice that lay their eggs in our hair and suck blood from our scalp. They are obligate parasites, meaning they cannot survive away from a human host for more than one or two days, Toloza said. To preserve this intimate and exclusive relationship, these insects have evolved in tandem with humans and our hominid relatives over millennia.

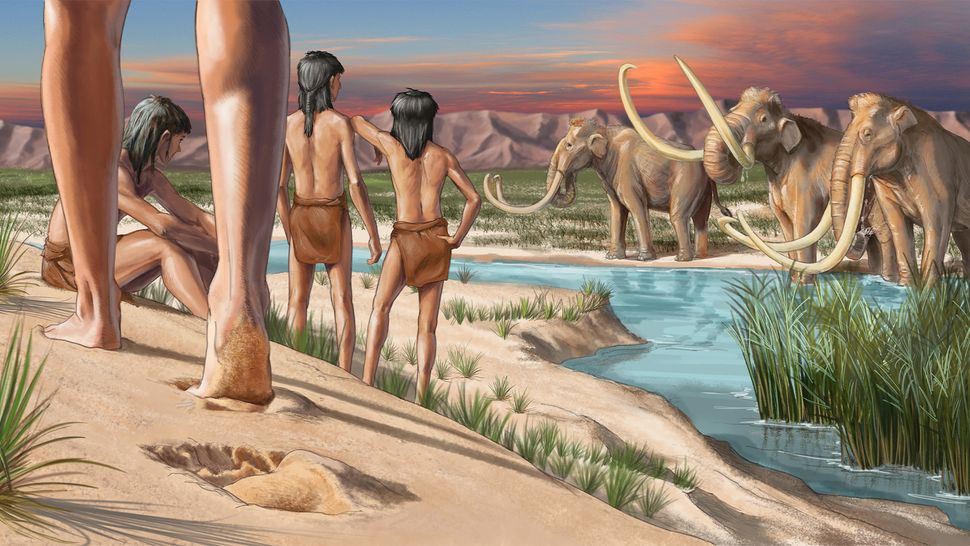

Related: Debate settled? Oldest human footprints in North America really are 23,000 years old, study finds

These tight evolutionary ties mean louse genomes contain clues about human movement across continents, Toloza said. In a previous study, researchers analyzed DNA from 75 human lice and detected differences between North American, European and Asian lice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In a new study published Wednesday (Nov. 8) in the journal PLOS One, researchers broadened the sample size and sequenced genes from 274 living head lice from 25 locations around the world. They confirmed that two genetically distinct groups of lice exist in Asia and Europe — but when it came to the Americas, the results were less clear-cut.

"North American lice have a strong pattern of hybridization," study lead author Marina Ascunce, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Florida and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Center for Medical, Agricultural and Veterinary Entomology, told Live Science.

While North American lice genes were a jumble of European and Asian ancestry, Central American lice were closely related to Asian lice and likely arrived there with the first humans to populate the Americas. "Lice from Honduras are closer to lice from Mongolia," Ascunce said. "This, we thought, was interesting."

Research suggests the first people to arrive in the Americas descend from an ancestral group of Ancient North Siberians and East Asians who may have also dispersed to Mongolia, which could explain genetic similarities between Mongolians and Native Americans.

To determine when Asian and European lice came into contact with each other in the Americas, the researchers plugged the genetic data into a model that took into account archaeological evidence of lice salvaged from mummies and ancient combs. They found that North American hybrids evolved after several waves of human migration from Europe in the last 100 years, including during the two world wars, but they couldn't draw conclusions about the influence of earlier European colonization, such as when Columbus set foot on American soil.

"We could detect the ancient colonization of the Americas by Asian people and also European colonization," Toloza said. "In South America, you find very marked information of European colonization, but mostly at the time of World War II," when there was a wave of emigration to Argentina.

Europeans mostly migrated to North and South America, so lice in Central America have retained a distinct Asian footprint, he added.

While the new analysis included more lice than previous work, these lice were not distributed evenly across continents, and the sample may still be too small to capture the entire picture, Alejandra Perotti, an associate professor of invertebrate biology at the University of Reading in the U.K. who was not involved in the research, told Live Science.

Nevertheless, "the paper confirms that early colonization came from East Asia" and that hybrid lice evolved as a result of "recent arrivals in the Americas, from the First and Second World Wars onwards," Perotti said.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.