Hidden colors and intricate patterns discovered on the 2,500-year-old Parthenon Marbles from ancient Greece

The ancient Greek statues were assumed to be spotlessly white, but a new study reveals that the Parthenon Sculptures once burst with color.

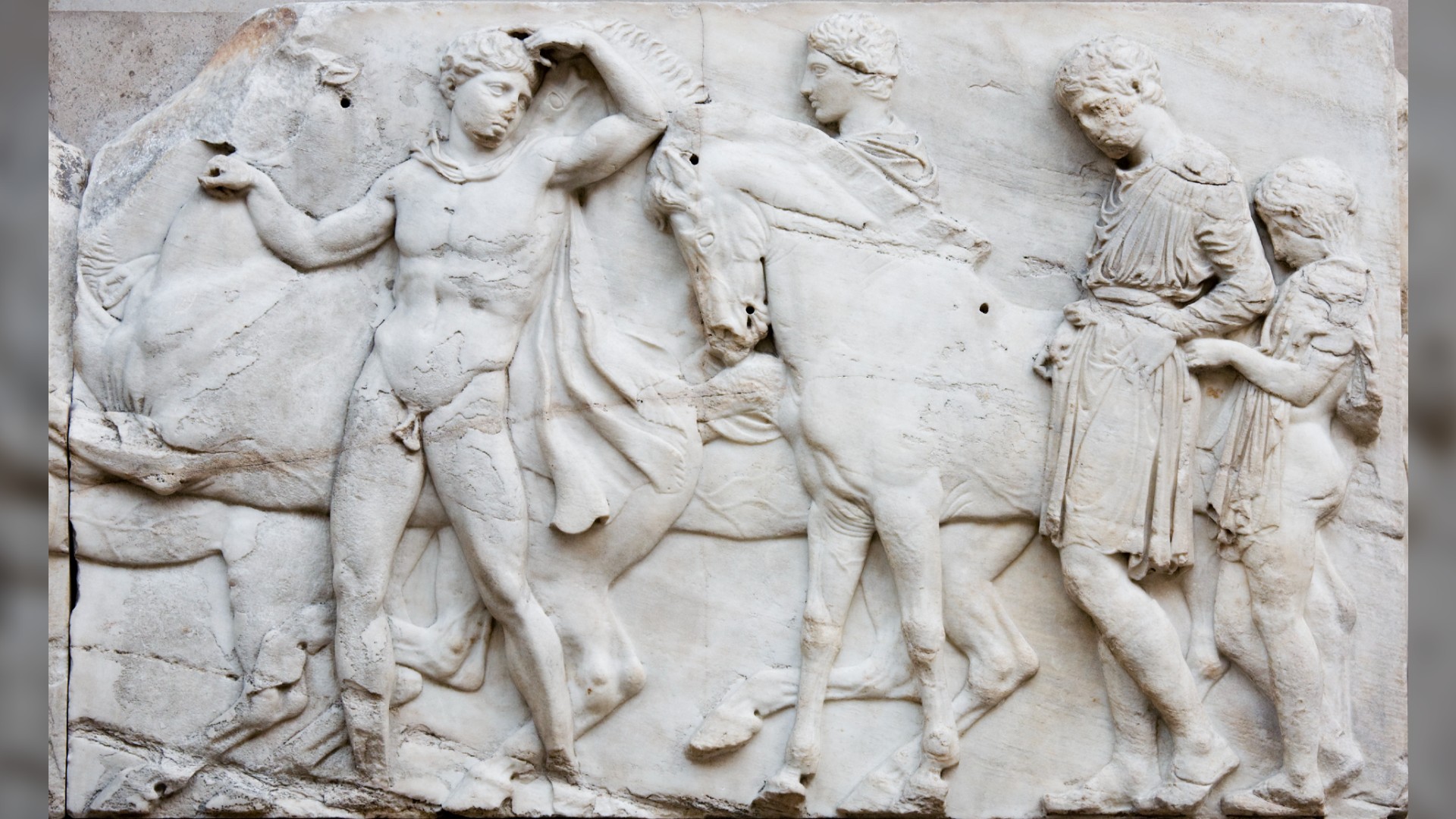

The Parthenon Sculptures, also called the Elgin Marbles, were crafted by ancient Greeks 2,500 years ago to decorate the outside of the Parthenon temple in Athens. Now housed at the British Museum in London, they, like many old sculptures, are a muted mix of white, gray and beige.

But a new study reveals that the famous sculptures' hues weren't always so drab — in fact, they were once painted with vibrantly colored and intricate patterns.

Bright Egyptian blues, whites and purples once covered the statues depicting deities and mythical creatures guarding the fifth-century-B.C. temple. The colors were used to represent the water that some figures rose from, the snakeskin of a mysterious sea serpent, the empty space and air in the background behind the statues, and figurative patterns on the robes of the gods, the researchers wrote in the study, which was published Wednesday (Oct. 11) in the journal Antiquity.

Related: 31 ancient temples from around the world, from Göbekli Tepe to the Parthenon

"The Parthenon sculptures at the British Museum are considered one of the pinnacles of ancient art and have been studied for centuries now by a variety of scholars," study lead author Giovanni Verri, a conservation scientist at the Art Institute of Chicago, said in a statement. "Despite this, no traces of colour have ever been found and little is known about how they were carved."

As paint often doesn't last long on marble and the sculptures' surfaces weren't prepared to enable adhesion from substances like paint, archaeologists long assumed that ancient Greek artists intentionally left the statues white. This even led historical restorations to remove past traces of paint found on the sculptures, the researchers said.

To investigate the statues' past, archaeologists used luminescent imaging, a technique that causes trace chemical elements from hidden paint on the sculptures' surfaces to glow. The team quickly discovered hidden patterns emerging on the statues' surfaces, revealing floral designs and smudged figurative depictions.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Four pigments were primarily found: a blue that was first created by the Egyptians and was the main color used by ancient Greeks and Romans, a purple tint made according to an unknown recipe (most purple was made with shellfish from the ancient Mediterranean, but this one wasn't), and two whites likely derived from the mineral gypsum and bone white, a pigment made from bone ash.

It's likely that these colors were "as visually important as the carving," the researchers wrote in the study, as "it was what the viewer saw."

"The elegant and elaborate garments were possibly intended to represent the power and might of the Olympian gods, as well as the wealth and reach of Athens and the Athenians, who commissioned the temple," Verri said. The researchers found traces of paint on the backs of the sculptures, meaning they were "certainly contemporary to the building" and likely were painted first and then placed on the temple.

The 17 sculptures, once part of a 525-foot-long (160 meters) marble frieze depicting classical Greek myths, were brought to the U.K. in the 19th century after being ripped from the walls of the Parthenon by Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin and Britain's ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. His involvement initially gave the sculptures their "Elgin Marbles" nickname.

Bruce sold the statues, which constituted roughly half of the surviving sculptures, to the British government in 1816. Now kept in the British Museum, the sculptures have been the subject of a formal repatriation controversy between the U.K. and Greece since 1983.

As the marbles are primarily fragments, the story they tell isn't completely clear. But they include sculptures of gods reacting to the birth of Athena, who is said to have burst from Zeus' swollen head after a mighty blow from the axe of Hephaestus, the Greek god of blacksmiths.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.