Hidden symbols and 'anomalies' discovered in 800-year-old 'Stone of Destiny' to be used in Charles III's coronation

A new look at the 13th-century Stone of Destiny reveals mysterious markings and other 'anomalies' that previously went unnoticed.

When King Charles III is crowned in London on May 6, the coronation ceremony will involve the Stone of Destiny, a Scottish carved seat that's at least 800 years old. Despite its long history, scientists only recently noticed never-before-documented symbols and other anomalies on the stone, they announced in a statement.

These anomalies — a copper alloy stain and the remains of gypsum plaster — suggest that the historical block, also known as the Stone of Scone, has unknown aspects of its history that aren't recorded in documents.

The stone was used in the coronation of Scotland's monarchs in the 13th century, and today, it is used in the coronation of the United Kingdom's monarch. As part of the modern-day ceremony, the stone is placed within the coronation chair that the monarch sits on. The stone was captured and moved from Scotland to England in 1296 and was not returned until the 20th century. Its history before the 13th century is unclear.

Now, scientists with Historic Environment Scotland, a public body that takes care of the stone, have performed a laser scan of the artifact and conducted scientific tests, revealing new information on it.

Related: Graves of dozens of kings from the time of King Arthur uncovered in Britain

Roman numerals?

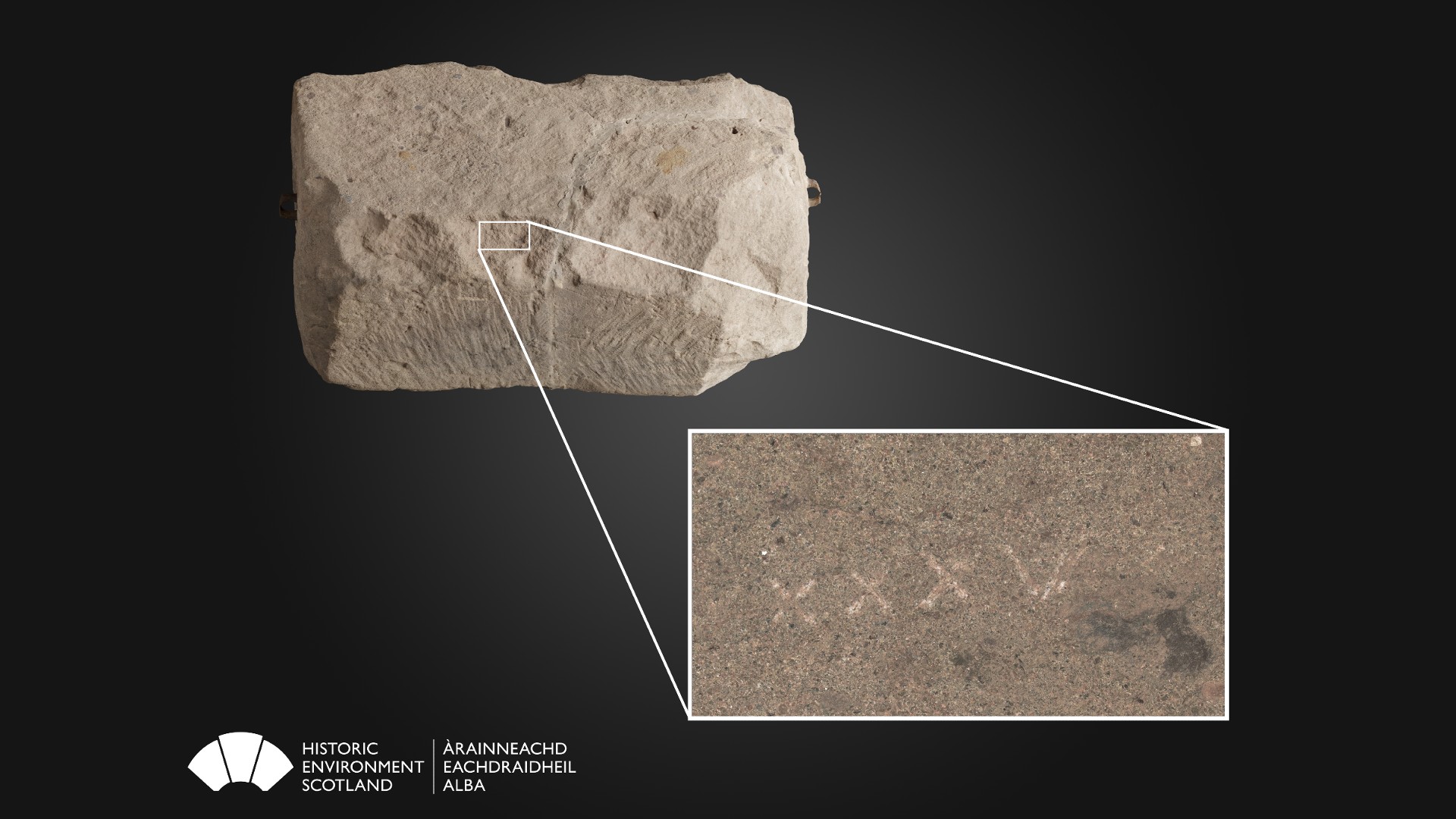

Among the finds were markings that look like Roman numerals. They include three X-shaped marks, followed by a marking that looks like a "v."

"The Roman numerals haven't been recorded before," Ewan Hyslop, head of research & climate change at Historic Environment Scotland, told Live Science in an email. "We do not know why they were carved or what they signify, but we hope that this will be an area for further research."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The carvings might not even be Roman numerals, but rather other symbols, said Ewan Campbell, a senior lecturer of archaeology at the University of Glasgow in the U.K., who was not involved in the new research.

"I think these are dubious as numerals — more likely crude crosses," Campbell told Live Science in an email. Based on the wearing of the stone and position of the markings, Campbell suspects they weren't etched into the stone until sometime after it was moved from Scotland to England in 1296.

Hints of a relic and plaster

The research team also identified a copper alloy stain on the stone by using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, a relatively non-destructive technique that works by measuring the chemical composition of materials such as rocks, minerals and sediments. The finding suggests that a copper or brass object was placed on the stone for a period of time at some point in its history.

"By far, the more important result is the presence of copper staining on the surface," Campbell said. "This suggest[s] some object, possibly a relic such as a saint's bell, was positioned on the stone for a long period."

Relics were popular in the Middle Ages and sometimes consisted of physical remains, such as the bones of a saint or holy person placed in a metal container, such as copper. Relics could also be artifacts associated with such a person. For example, pieces of wood that were reportedly from the cross that Jesus was crucified on were popular relics.

The analysis also revealed the presence of gypsum plaster on the Stone of Destiny. This suggests that at some point a plaster cast of the artifact may have been made.

The existence of a cast is unexpected, as no records mention a cast being made of the stone, Sally Foster, a professor of heritage and conservation at the University of Stirling, told Live Science in an email. "I have not encountered any stories of, or evidence for, the stone being replicated in this way," Foster said.

While it's not clear how the gypsum plaster got on the stone, the recent scans and tests will make it easier for scholars to study the stone. "The Stone of Destiny is rarely moved and it's not easy for scholars and the public to look at it in its entirety, close-up or for any extended period,"

The laser scan led to the creation of a virtual 3D image of the stone that is now available online to scholars and the public alike.

"The availability of the [online model] now allows us all to see and review some of that evidence for ourselves — we can all become detectives if we look for the ways in which the stone has been modified through time by activities that left their marks on its fabric," Foster said.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.