Humans faced a 'close call with extinction' nearly a million years ago

The human population may have lingered at about 1,300 for more than 100,000 years, and that population bottleneck could have fueled the divergence between modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Humans might have almost gone extinct nearly 1 million years ago, with the world population hovering at only about 1,300 for more than 100,000 years, a new study finds.

This close call with extinction may have played a major role in the evolution of modern humans and their closest known extinct relatives, the thick-browed Neanderthals and the mysterious Denisovans, researchers added.

Previous research suggested that modern humans originated about 300,000 years ago in Africa. With so few fossils from around that time, much remains uncertain about how the human lineage evolved before modern humans emerged.

To learn more about the period near the evolution of modern humans, scientists investigated the genomes of more than 3,150 present-day modern humans from 10 African populations and 40 non-African ones. They developed a new analytical tool to deduce the size of the group making up the ancestors of modern humans by looking at the diversity of the genetic sequences seen in their descendants.

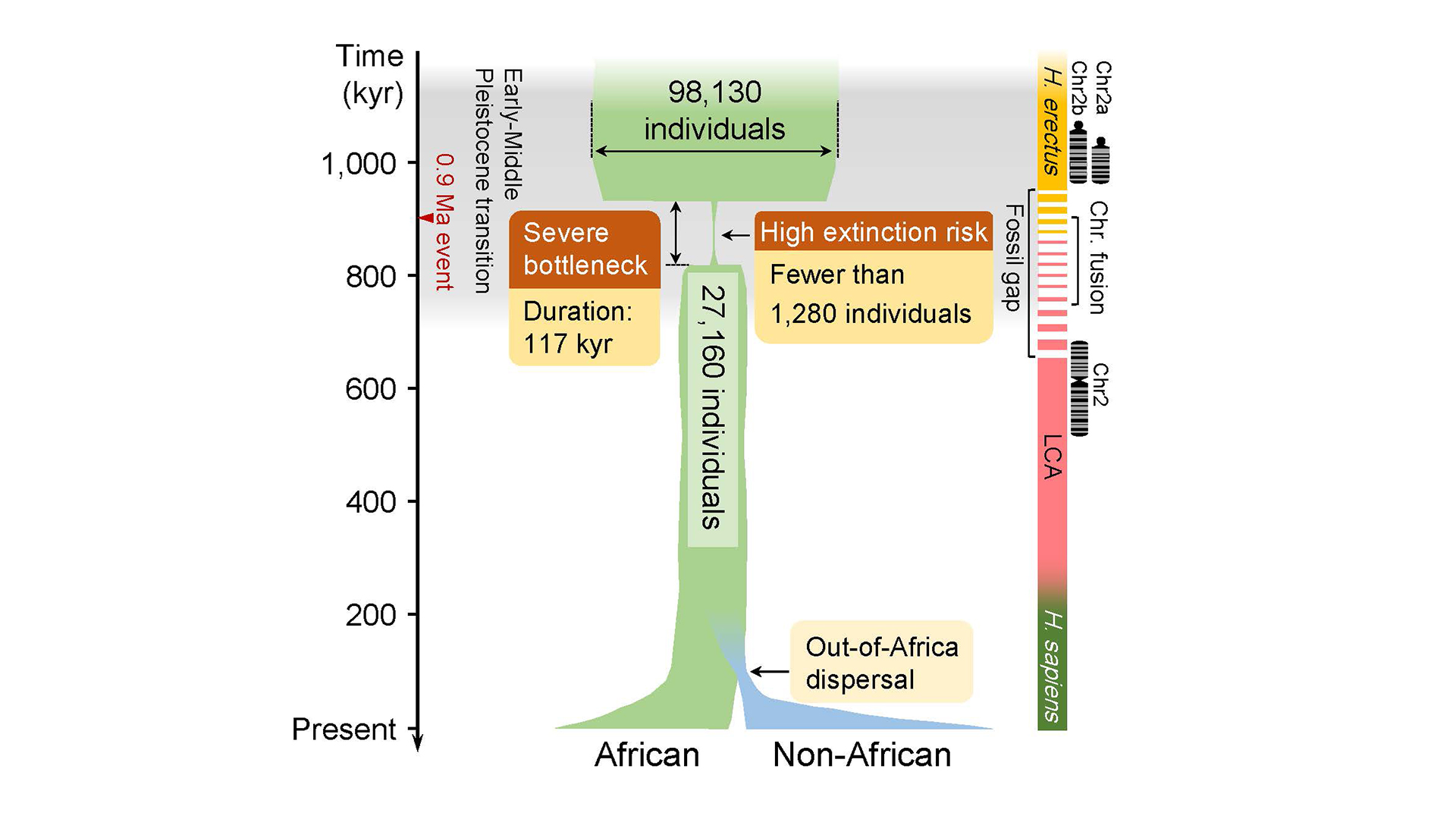

The genetic data suggest that between 813,000 and 930,00 years ago, the ancestors of modern humans experienced a severe "bottleneck," losing about 98.7% of its breeding population.

Related: Human and ape ancestors arose in Europe, not in Africa, controversial study claims

"Our ancestors experienced such a severe population bottleneck for a really long time that they faced a high risk of extinction," study co-lead author Wangjie Hu at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers estimated the modern human breeding population numbered about 1,280 for about 117,000 years.

"The estimated population size for our ancestral lineage is tiny, and certainly would have brought them near to extinction," Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London who was not involved in the new study, told Live Science.

The scientists noted this population crash coincided with severe cooling that resulted in the emergence of glaciers, a drop in ocean surface temperatures, and perhaps long droughts in Africa and Eurasia. Scientists still don't know how this climate change might have affected humans because human fossils and artifacts are relatively sparse during this time, perhaps because the population was so low.

Previous research suggested that the last common ancestor shared by modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans lived about 765,000 to 550,000 years ago, about the same time as the newfound bottleneck. This suggests the near-eradication was potentially in some way linked to the evolution of the last common ancestor of modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans.

If this last common ancestor lived during or soon after the bottleneck, the bottleneck may have played a role in splitting ancient human groups into modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans, Stringer explained. For instance, it might have split humans into tiny separate groups, and over time, differences between these groups would prove significant enough to divide these survivors into distinct populations — modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans, he said.

In addition, prior work suggested that about 900,000 to 740,000 years ago, two ancient chromosomes fused to form what is currently known as chromosome 2 in modern humans. Since this coincides with the bottleneck, these new findings suggest the near-eradication of humans may have some link with this major change in the human genome, the researchers noted.

"Since Neanderthals and Denisovans share this fusion with us, it must have occurred before our lineages split from each other," Stringer said.

Future research may apply this new analytical technique "to other genomic data, such as that of Neanderthals and Denisovans," Stringer said. This might reveal whether they similarly underwent major bottlenecks.

The study was published online Thursday (Aug. 31) in the Sept. 1 issue of the journal Science.