Humans reached Argentina by 20,000 years ago — and they may have survived by eating giant armadillos, study suggests

The discovery of butchered bones belonging to a glyptodont, a giant relative of the armadillo, suggests that humans were living in Argentina 20,000 years ago.

Ancient humans may have butchered and eaten a giant armadillo-like creature around 20,000 years ago in what is now Argentina, a new study finds.

The discovery of the butchered bones supports a growing body of evidence that people spread throughout the Americas much earlier than previously assumed.

During the Late Pleistocene epoch (129,000 to 11,700 years ago), ice sheets and glaciers covered much of the planet, particularly during the Last Glacial Maximum, a period around 26,000 to 20,000 years ago when the ice age was at its height. While archaeologists previously thought that the first Americans arrived by journeying along a land bridge connecting Siberia with Alaska 13,000 years ago, archaeological sites discovered in North and South America in the last decade point to humans arriving in the region much earlier.

In a new study published Wednesday (July 17) in the journal PLOS One, researchers revealed they found cut marks on the fossil remains of a glyptodont known as Neosclerocalyptus — a giant, extinct armadillo relative. These marked bones, found in the Pampean region of Argentina, may be among the earliest examples of humans interacting with megafauna in South America.

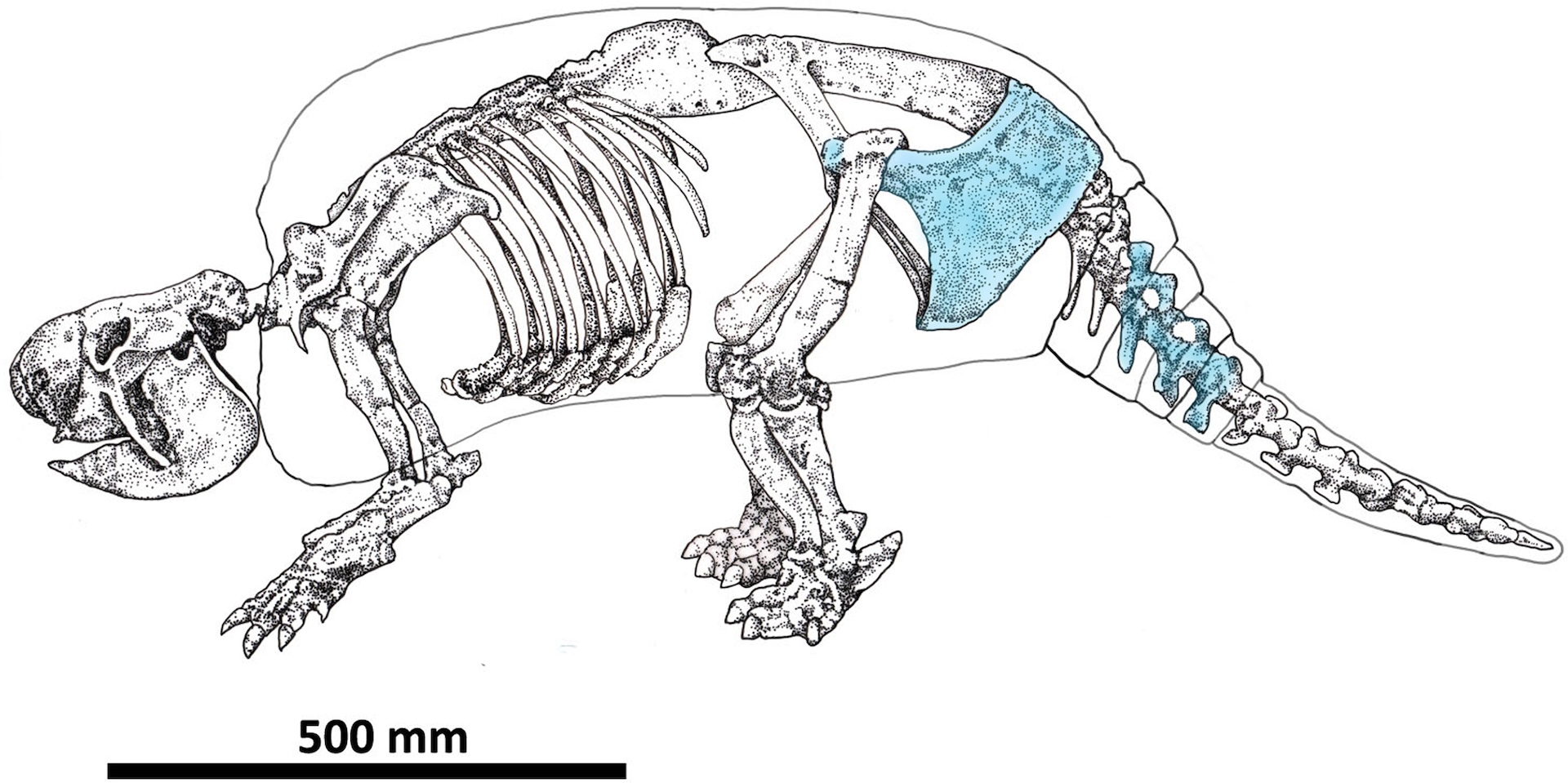

The incomplete animal skeleton, found along the banks of the Reconquista River on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, included parts of the pelvis and tail as well as a portion of the carapace — bony plates that covered the top of the animal's body. The researchers carbon-dated a fragment of pelvic bone to 21,090 to 20,811 years ago, which was consistent with the geological dates of the sediment in which the animal was found.

Related: How did humans first reach the Americas?

To determine whether the cut marks were human-made, the researchers photographed and created 3D scans of the animal bones. Some of the marks had a V-shaped cross-section, which the team believe is highly suggestive of stone tool butchering marks. In total, the researchers counted 32 cut marks across the animal's bones. Using a variety of statistical techniques to classify and compare the marks quantitatively, they concluded that the pattern could not have been random — the cuts were made by humans using tools.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team ruled out other potential causes of the marks, including carnivores — whose tooth marks are usually U-shaped — and natural weathering of the bone after the death of the animal, as there was significant evidence that the animal's body was buried quickly after death, preventing degradation from weather or scavengers.

The location of cut marks in different areas of the body reveals a butchering sequence, the researchers concluded, and implies that ancient humans acquired — and presumably ate — a large amount of meat from the muscles of the pelvis and tail of the giant armadillo.

"It is possible that people targeted glyptodonts because of their size (~300 kilos [660 pounds]) and the large muscle packs they possess," study co-author Miguel Delgado, a paleoanthropologist at the National University of La Plata in Argentina, told Live Science in an email.

In addition to revealing the interactions between humans and megafauna, the results of this study "push back the chronological frame of both human presence and human- megafauna interactions nearly 6,000 years earlier than recorded for other sites in southern South America," the authors wrote in their study.

Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that the authors' advanced approach to this research is commendable but requires more study, particularly as no human-made tools were found at the site.

"Establishing the degree to which human actions of butchery are similar to and different from the breadth of natural processes that modify bone is needed to support their claim for human presence at this site ~21,000 years ago," Davis said.

The researchers noted the "need to establish a stronger link between fossil bones with cut marks and the archaeological record," but they hope to do this soon.

"While we haven't found any tools yet, it's worth noting that we've only excavated a small portion of the site, and there may be more evidence, such as lithic tools," Delgado said.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.