Largest-ever genetic family tree reconstructed for Neolithic people in France using ancient DNA

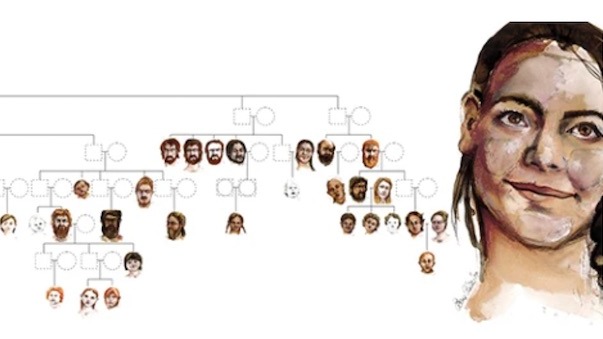

Researchers created two extensive Neolithic family trees using ancient DNA.

Using ancient DNA, archaeologists in France have pieced together two elaborate Neolithic family trees that span multiple generations, making them the largest ancestral human record ever reconstructed.

The family trees are based on a 6,700-year-old funerary site known as Gurgy, which is located in the Paris Basin region of northern France. Researchers excavated the site in the mid-2000s but, due to advancements in obtaining and analyzing ancient DNA data, recently began studying the genomes of 94 of the 128 individuals, which included children and adults, whose remains were recovered from the site, according to a study published July 26 in the journal Nature.

Neolithic communities first emerged roughly 12,000 years ago in the Near East, a region that encompasses West Asia, Southeastern Europe and North Africa. During this time period, many human groups transitioned from hunting and gathering to farming. This lifestyle change enabled people to put down roots and settle into communities that spread across generations, leading to the extensive burial plot.

"The size of a family tree that huge for that time period" was mind boggling, lead study author Maïté Rivollat, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Archaeology at Ghent University in Belgium, told Live Science. "We realized that we could explore social aspects of this community."

Related: Largest family tree ever created retraces the history of our species

The site was composed of a single graveyard with no monument or grave goods, and many of the bones were "not well preserved and corroded," Rivollat said.

Still, "the bones were good enough [to extract] DNA," she said, "and we were able to get DNA from 94 of the individuals."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers discovered that the family's descendants stemmed from a single "founding father." His skeleton was unique, since it was initially buried at an unknown site and was later moved near his kin at Gurgy, according to a statement. (The archaeologists also found the remains of a woman buried next to him but were unable to extract any DNA.)

By analyzing the mitochondrial DNA (maternal lineages) and Y-chromosome (paternal lineages) data, as well as each individual's age at death and genetic sex, the researchers constructed two family trees. The first tree connected 64 individuals across seven generations and is the largest to date, and the second contained 12 people from five generations, according to the study.

Soon, a "patrilineal pattern" emerged in which generations were linked through the male line of descendants. Researchers also noticed that while the men stayed within the community in which they were born, the women left, according to the statement.

"The women who were buried there weren't related and came from somewhere else," Rivollat said. "We also noticed that inbreeding wasn't occurring and think that this system of female movements avoided that from happening."

Another interesting aspect of the community was that it lacked half-siblings and that sons and daughters shared the same parents, suggesting that members of this family group weren’t polygamous but rather were monogamous, according to the statement.

"It became apparent that the descendants knew who was buried there," Rivollat said. "The closer they were buried together, the closer they were related."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.