Lasers reveal 1,000-year-old Indigenous road near Chaco Canyon that aligns with the winter solstice

Researchers think the Indigenous roads were more about cosmology than traffic.

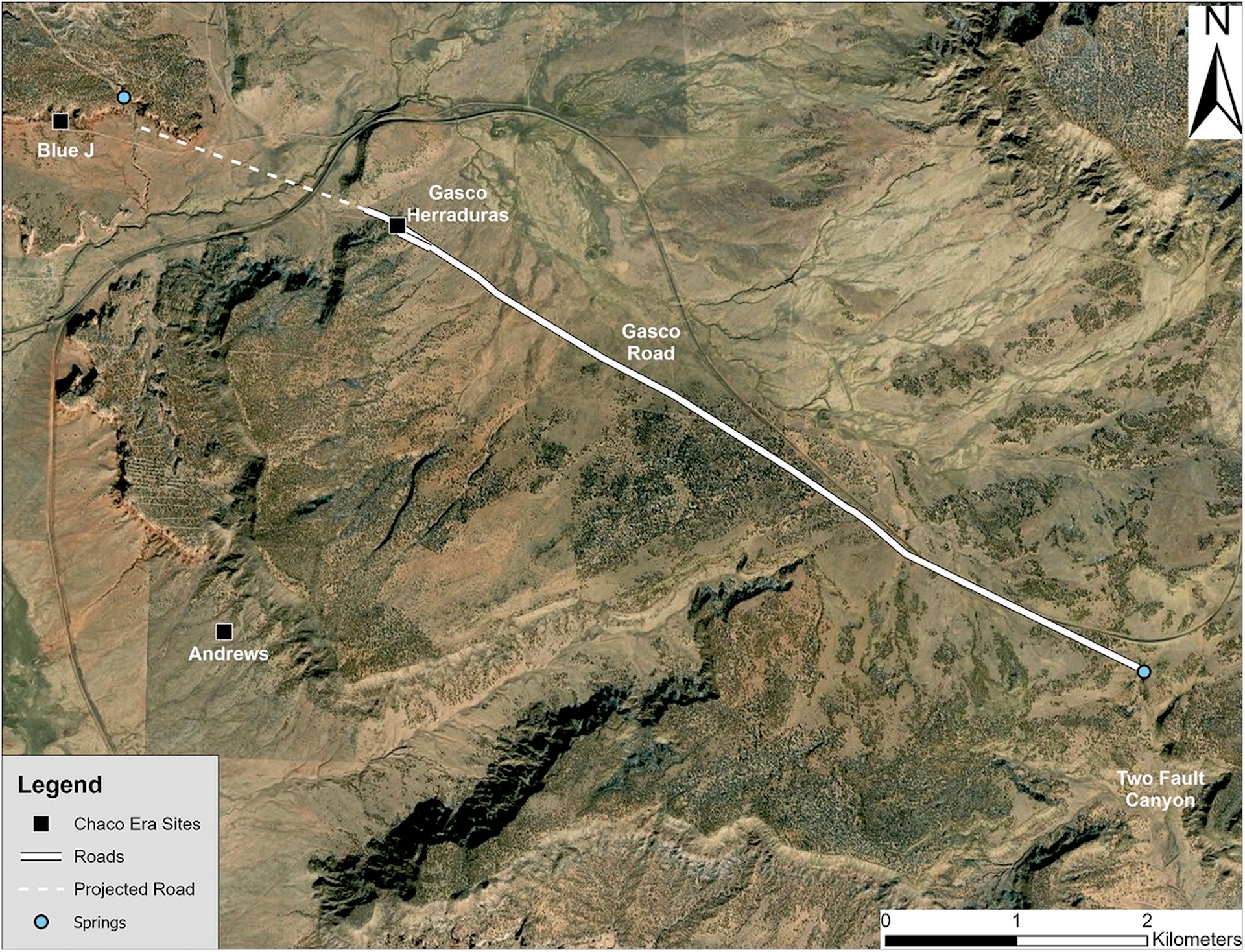

Lasers have revealed a 1,000-year-old sacred road near Chaco Canyon in New Mexico. Researchers say the road was part of an Indigenous ritual landscape, serving as a path between natural springs and aligning with the sunrise on the winter solstice, a new study finds.

Until now, researchers thought the road at the Gasco site may have linked Indigenous settlements in the area. But new research shows that not only is a sacred road there much longer than they thought, it also has a previously unknown road running almost parallel to it. In addition, the two roads align with the winter solstice sunrise over Mount Taylor, which remains a sacred mountain among Indigenous peoples today, the researchers wrote in the study.

The discoveries at Gasco, west of Albuquerque and about 50 miles (80 kilometers) south of Chaco Canyon, indicate that the roads made by this Indigenous culture were not just for regular traffic but were integral to their system of cosmological beliefs, the researchers wrote.

"One of the really exciting things about the work we've been doing with Chacoan roads is that they're forcing us to reconceptualize what a road might be, what a road might mean," study lead author Robert Weiner, an archaeologist at Dartmouth College, told Live Science.

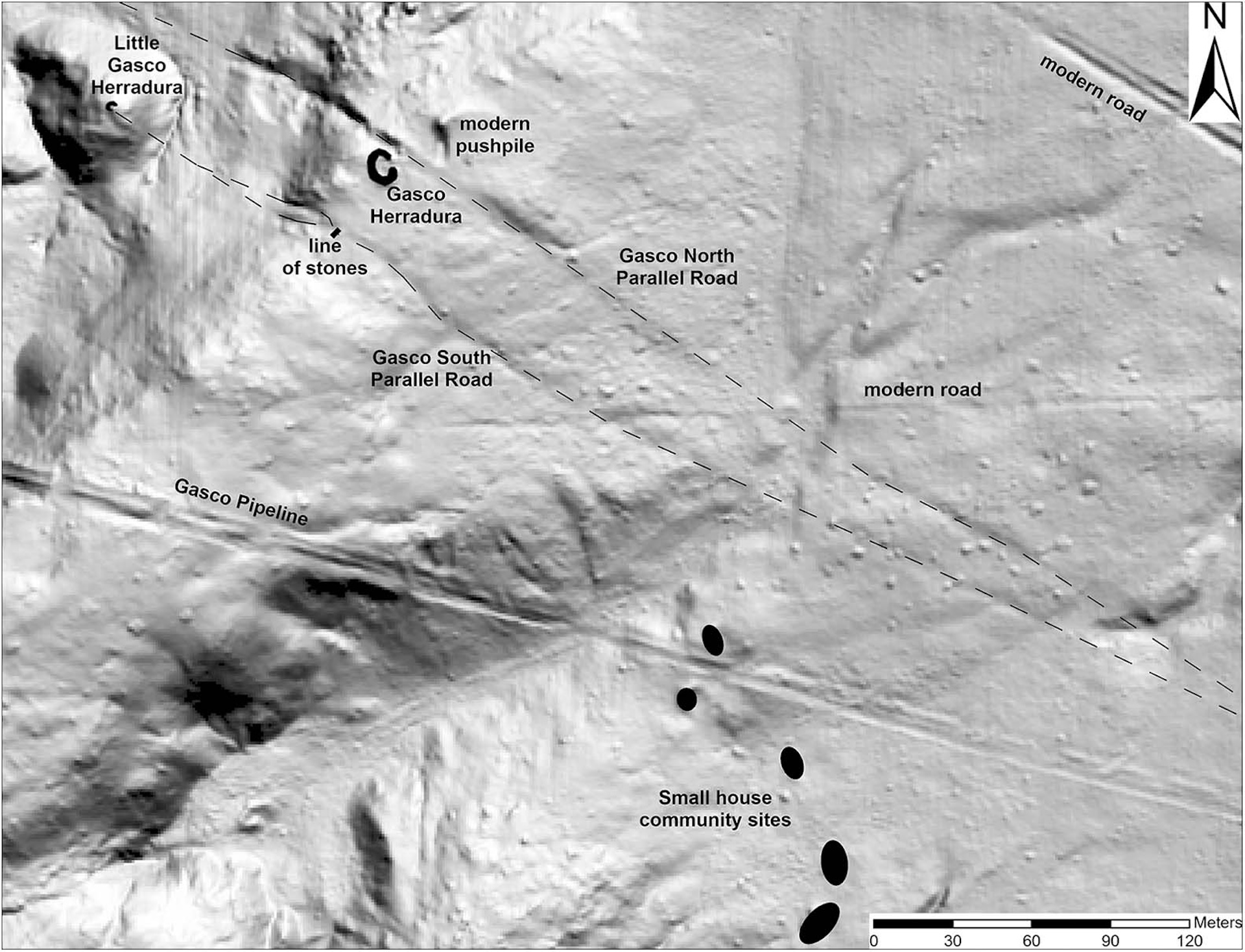

The researchers used public maps based on lidar — an analog of radar that uses laser pulses to reveal a landscape hidden beneath vegetation — to determine that the known road at the Gasco site was almost 4 miles (6 km) long, instead of the few hundred feet that had been found before. They then confirmed their new understandings of the site with fieldwork in 2021 and 2022, according to the study published Jan. 24 in the journal Antiquity.

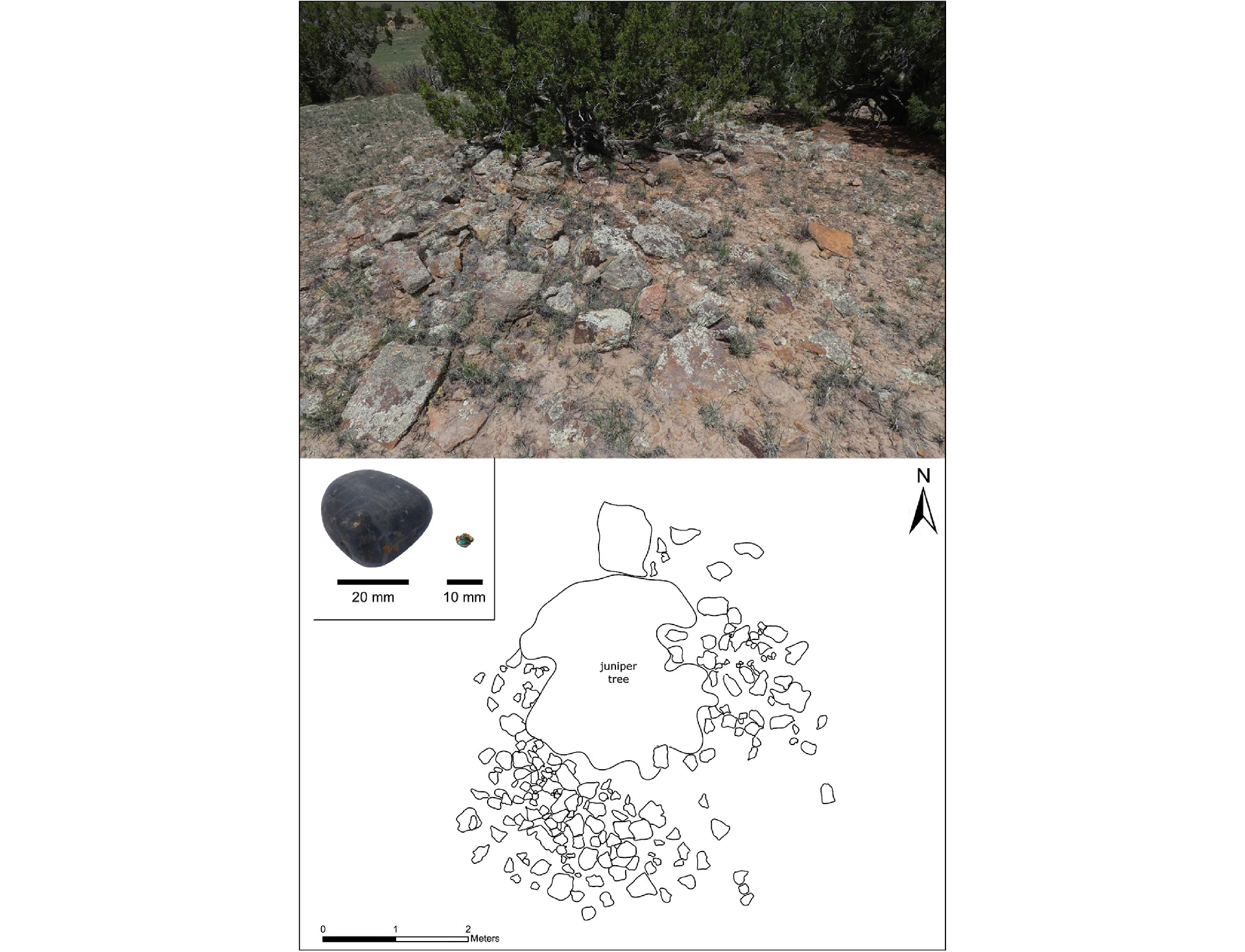

The research also discovered a second, almost parallel road that ran about 115 feet (35 m) to the south of the first road, as well as an additional "herradura" — the remains of a horseshoe-shaped wall of rocks, which may have been a roadside shrine.

Related: The 1st Americans were not who we thought they were

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mysterious culture

Chaco culture thrived in parts of the American Southwest roughly between A.D. 850 and 1250, centuries before the European arrival. Weiner said he thinks the culture may have started as a religious movement among the local people, but little is known about the details of their beliefs.

The Chacoans are famous for the long-abandoned pueblo buildings at Chaco Canyon and other sites, but it's now thought that prolonged droughts and other crises caused the culture's demise.

Several Indigenous groups, sometimes termed "Pueblo Indians," are descended from the Chacoans, including the Hopi and the Zuni peoples, while the Diné people, often known as the Navajo, also live in the region.

The researchers used public lidar maps of the region to determine the locations of two nearly-parallel roads and other landscape features at the Gasco site.

Both the northern and southern roads travel past "herraduras" — the remains of horseshoe-shaped walls built with rocks that probably served as roadside shrines.

The researchers extrapolated the Gasco site roads to determine they may have linked local freshwater springs.

Chacoan roads

The unusual formation of two almost-parallel roads has been seen at other Chacoan sites and may reflect a dualistic principle in their cosmology, Weiner said.

These sacred or "monumental" roads were cut into sandstone bedrock and were about 30 feet (9 meters) wide — much wider than needed by a society without wheeled vehicles or pack animals, the researchers wrote. They also had staircases and ramps in some areas, and parts were lined with mounds of sandstone and earth from the excavations of the roads.

Weiner said the two herraduras beside the roads — one that was already known beside the northern road, and the other that was revealed beside the southern road by the latest research — had probably served as focal points for ritual activity during sacred processions. The idea is supported by the presence of shards of ceramics and shaped stones that may have been offerings, and it may be that one road and the nearby herradura were used in winter and the other road and herradura were used in summer.

Although the roads may have been used at times for utilitarian purposes, such as transporting timber, it seems they mainly served a ceremonial role within Chacoan beliefs, he said.

University of Colorado Boulder anthropologist Stephen Lekson, an expert on the Chaco culture who was not involved in the new research, told Live Science that the prehistoric road network built by the Chacoans in several places formed an archaeological site roughly the size of Ohio.

"The geography of Chaco's domain is uniquely preserved by its roads, as well as much of Chaco cosmology," he said, and the authors highlight how archaeologically rich even a small portion of the road network could be.

But Lekson warned that many Chacoan sites are now threatened by energy projects on public lands — developments that could "destroy this key chapter of Pueblo and Navajo history," he said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.