Lasers reveal prehistoric Irish monuments that may have been 'pathways for the dead'

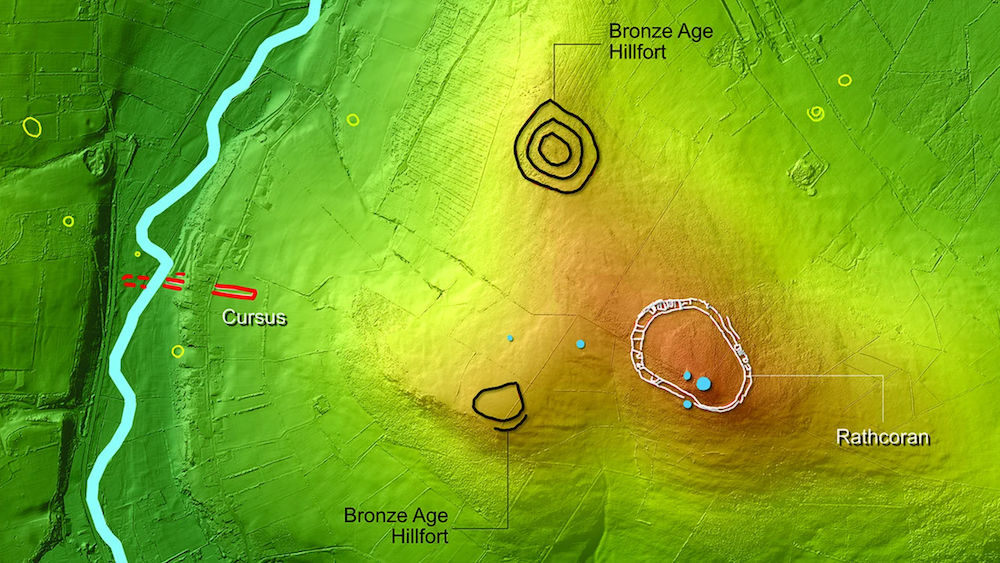

Archaeologists used lidar to detect a cluster of rare Neolithic monuments hidden in farmland in Ireland.

Lasers have revealed hundreds of previously undetected prehistoric monuments, including five rare ones, clustered in a swath of farmland in the Irish countryside.

Archaeologists discovered the monuments in Baltinglass, a town in County Wicklow in eastern Ireland, using lidar (light detection and ranging), a technique in which an aircraft flies overhead while a machine shoots laser pulses toward the ground. These pulses hit objects and then bounce back, helping researchers map the landscape's topography.

The area examined by the researchers was occupied during the Early Neolithic (beginning around 3700 B.C.) and the Middle to Late Bronze Age (1400 to 800 B.C.). However, evidence of occupation during a 2,000-year stretch between the two periods, known as the Middle Neolithic, has been scarce — until now, according to a study published Thursday (April 25) in the journal Antiquity.

Despite years of agricultural plowing that had damaged some of the monuments, lidar revealed three-dimensional models of the landscape peppered with structures, including several "rare" cursus monuments, which are long, narrow, large-scale earthwork enclosures that may have had a ritual purpose. The grouping is considered the largest cursus cluster in both Ireland and Britain, according to a statement.

"I began working on this area about 10 years ago as part of my PhD and originally the idea was that this was the place in Ireland with the biggest and largest Bronze Age hillfort monuments in the country," study author James O'Driscoll, an archaeologist at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, told Live Science. "After various surveys, we slowly started to realize that it wasn't just Bronze Age but there were also a lot of Neolithic monuments there. Around 2014, a local identified one of these cursus monuments, and that's all we knew prior to the lidar survey."

The new lidar survey revealed four more, "which is why it's such an important discovery and was something we didn't think would appear, because groups of cursus monuments just don't exist in Ireland," O'Driscoll said. "You have maybe a half dozen in Britain, but in Ireland there's only about 20 known cursus monuments and they occur in isolation."

Related: Remains of 4,000-year-old 'lost' tomb discovered in Ireland

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While most of the five range in size between 492 and 656 feet (150 and 200 meters) long, the largest stretches roughly 1,312 feet (400 m) long, according to the study.

And considering that people created these monuments at a time before the invention of bulldozers and excavators, it's impressive, to say the least.

"Since these [were built during the] Neolithic, there were no metal tools and they would have likely used wooden shovels," O'Driscoll said. "It shows just how much resources, time and effort went into building them, since this is a sizable settlement."

Archaeologists think that the monuments may have served several purposes, including an association with "major solar events," farming and "pathways for the dead," according to the statement.

For example, four of the cursus monuments are aligned toward the "rising sun of the summer solstice," which marks the peak of the growing season, according to the study.

These massive monuments were also likely devoted to the dead, O'Driscoll said. "While we don't know the actual rituals that took place there, the layouts suggest that they may have been used as either processional routes for mourning or a way to move the dead onto heaven."

The monuments "help us understand the lifeways of these Neolithic people, who were first-generation farmers," he added. "We now have a better understanding of the importance farming had on these communities, which quickly became central to their lives."

Researchers next plan to analyze soil samples from the site to get a better understanding of the animals and plants that were there during the Early Neolithic.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.