Lasers reveal secrets of lost Silk Road cities in the mountains of Uzbekistan

On the Silk Road, these lost twin cities may have sustained themselves in a foreboding landscape with metallurgy and commerce.

Hidden in the towering mountains of Central Asia, along what has been called the Silk Road, archaeologists are uncovering two medieval cities that may have bustled with inhabitants a thousand years ago.

A team first noticed one of the lost cities in 2011 while hiking the grassy mountains of eastern Uzbekistan in search of untold history. The archaeologists trekked along the riverbed and spotted burial sites along the way to the top of one of the mountains. Once there, a plateau dotted with strange mounds spread before them. To the untrained eye, these mounds wouldn't have looked like much. But "as archaeologists..., [we] recognize them as anthropogenic places, as places where people live," says Farhod Maksudov of the National Center of Archaeology of the Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences.

The ground, too, was littered with thousands of pottery shards. "We were kind of blown away," says Michael Frachetti, an archaeologist at Washington University in St. Louis. He and Maksudov had been in search of archaeological evidence of nomadic cultures that grazed their herds on the mountain pastures. The researchers never expected to find a 30-acre medieval city in a relatively inhospitable climate around 7,000 feet above sea level.

But this site, called Tashbulak, after the area's present-day name, was only the beginning. While excavating in 2015, Frachetti met with one of the region's only current inhabitants — a forestry inspector who lives with his family a few miles from Tashbulak. "He said, 'In my backyard, I've seen ceramics like that,'" Frachetti recalls. So the archaeologists drove to the forestry inspector's farmstead, where they found that his home rested on a familiar-looking mound.

"Sure enough, he's living on a medieval citadel," Frachetti says. From there, the researchers looked out at the landscape and saw even more mounds. "And we're like, 'Oh my gosh, this place is humongous,'" Frachetti adds.

This second site, named Tugunbulak, is described for the first time in a study published on October 23 in Nature. The researchers used remote-sensing technology to map what they describe as a sprawling, nearly 300-acre medieval city three miles from Tashbulak that was integrated into the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road.

"It's a pretty remarkable discovery," says Zachary Silvia, an archaeologist at Brown University, who researches this period of Central Asian history and culture. (Silvia was not involved in the new work, but he authored a commentary about it that was published in the same issue of Nature.) Though more excavations are needed to confirm Tugunbulak's scope and density, "even if it turns out to be half the size [estimated here], that's still a huge discovery," he says — and one that could force a rethink of just how sprawling the Silk Road networks were.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

On conventional maps of the Silk Road, trade routes spanning the Eurasian continent tend to avoid the mountains of Central Asia as much as possible. Low-lying cities such as Samarkand and Tashkent, which have the arable land and irrigation necessary to support their bustling populations, are seen as having been the real destinations for trade. On the other hand, the nearby Pamir mountains, where Tashbulak and Tugunbulak are located, are rugged and mostly nonarable because of their elevation. (Today less than 3 percent of the world's population lives more than 2,000 meters, or about 6,500 feet, above sea level.)

Yet despite the limited resources and frigid winters, people did live at Tashbulak and Tugunbulak from the eighth to 11th centuries C.E., during the Middle Ages. Eventually, whether slowly or all at once, the settlements were abandoned and left to the elements. In the mountains, the landscape changed quickly, and the remains of the cities were worn down by erosion and blanketed with sediment. A thousand years later, what's left are mounds, plateaus and ridges that are hard to map comprehensively with the naked eye.

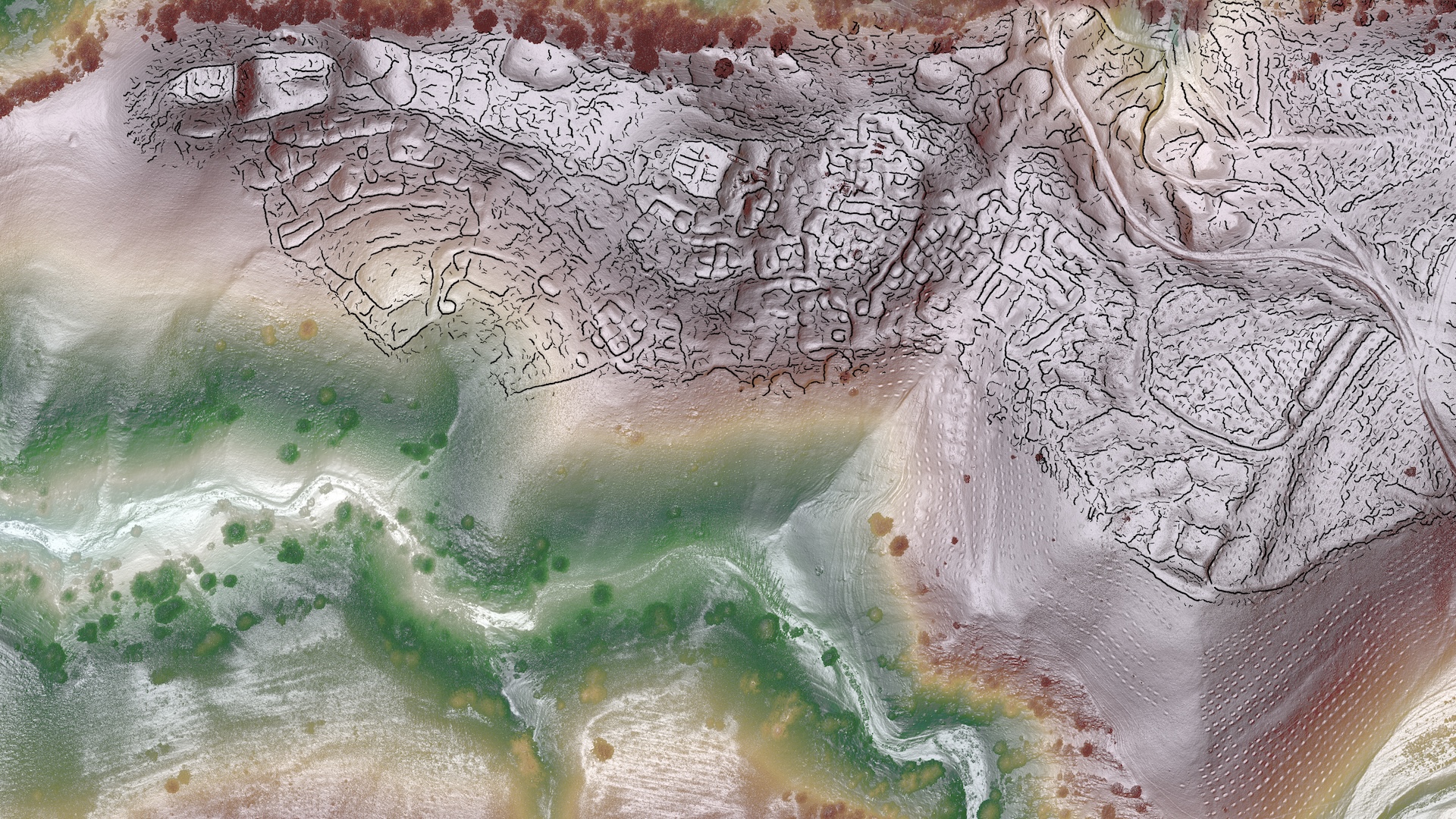

To get a detailed lay of the land, Frachetti and Maksudov equipped a drone with remote-sensing technology called lidar (light detection and ranging). Drones are tightly regulated in Uzbekistan, but the researchers managed to get the necessary permits to fly one at the site. A lidar scanner uses laser pulses to map the features of land below. The technology has been increasingly used in archaeology — in the past few years it has helped uncover a lost Maya city sprawling beneath the rainforest canopy in Guatemala.

At Tashbulak and Tugunbulak, the result was a relief map of the sites with inch-level detail. With the help of computer algorithms, manual tracings and excavations, the researchers mapped out subtle ridges that likely represented walls and other buried structures.

Related: 32 times lasers revealed hidden forts and settlements from centuries ago

This method has its limitations, Silvia says — namely, it often turns up false positives. It's also impossible to confirm which features come from which time period without more excavation. Such work has been ongoing at Tashbulak but has only just begun at Tugunbulak. (The scans and some excavation were completed in 2022, and Frachetti's team returned to Tugunbulak this past summer to continue excavation. The researchers have yet to publish their findings.) For now, the lidar map of Tugunbulak appears to show a massive medieval complex, complete with a citadel, buildings, courtyards, plazas and pathways, bounded by fortified walls. Along with pottery, the team has excavated kilns, as well as clues that workers in the city smelted iron ores, Frachetti says.

Metallurgy may be a key part of how the city could sustain itself at such a high altitude. The mountains are rich in iron ore and have dense juniper forests, which could be burned to fuel the smelting process. The researchers have also uncovered coins from across modern-day Uzbekistan, Maksudov says, suggesting the city may have been a hub for trade. It doesn't appear to have been strictly a mining settlement, either — at Tashbulak, a cemetery contains the remains of women, elderly people and infants.

"We have realized that this was a large urban center, which was integrated into the Silk Road network and dragged the Silk Road caravans toward mountains ... because they had their own products to offer," Maksudov says.

"There is a relationship between these cities" in the highlands and those in the lowlands, says Sanjyot Mehendale, an archaeologist and chair of the Tang Center for Silk Road Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. The trading networks of the Silk Road were "very, very fluid," and societies once considered peripheral and remote, such as those of Tashbulak and Tugunbulak, "were part of a network that stretched all across Eurasia," she says. "You can no longer look at these areas and perceive them as remote or less developed."

Mehendale became involved with the work at Tugunbulak after the lidar study was completed, and she went to the site to excavate this past summer. She's now most interested in reconstructing what the city was like across its life span. Who were the inhabitants? How did the population change over seasons or centuries?

The answers to all these questions are likely there, buried in the sediment. The research team, Silvia says, "has got a lifetime of work."

This article was first published at Scientific American. © ScientificAmerican.com. All rights reserved. Follow on TikTok and Instagram, X and Facebook.

Allison Parshall is an associate news editor at Scientific American who often covers biology, health, technology and physics. She edits the magazine's Contributors column and weekly online Science Quizzes. As a multimedia journalist, Parshall contributes to Scientific American's podcast Science Quickly. Her work includes a three-part miniseries on music-making artificial intelligence. Her work has also appeared in Quanta Magazine and Inverse. Parshall graduated from New York University's Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute with a master's degree in science, health and environmental reporting. She has a bachelor's degree in psychology from Georgetown University.