Lavish, 800-year-old tombs in China may hold remains of Great Jin dynasty elites

Three newfound brick tombs date to the Golden Khanate, a non-Chinese people who ruled in northern China centuries ago.

Three centuries-old brick tombs discovered in northeastern China may hold the remains of a non-Chinese people that ruled the region nearly a millennium ago.

The tombs, located in the city of Changzhi in Shanxi province, are from the Jurchen Jin — or "Great Jin" — dynasty, which ruled in northern China between 1115 and 1234.

But the Jurchen Jin rulers were not ethically Han, the dominant ethnicity in China today. Instead, they were a seminomadic people from the northeast of China, Julia Schneider, a professor of Chinese history at University College Cork in Ireland who was not involved in the discovery, told Live Science in an email.

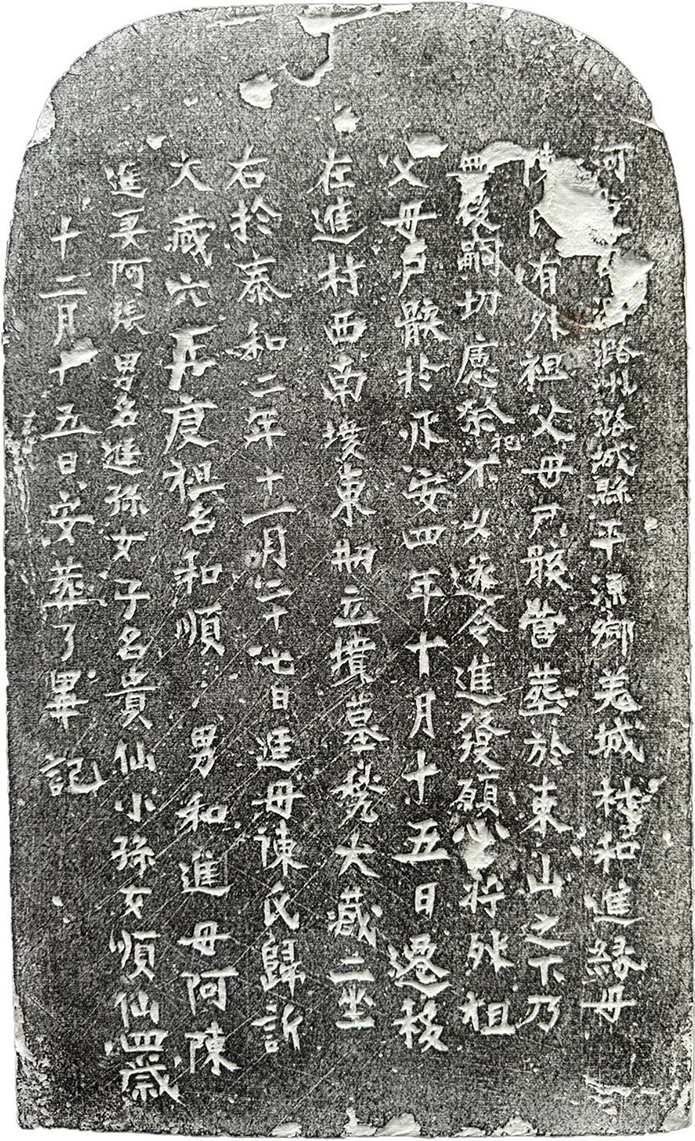

According to a report of the discovery in China Daily — the official newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party — the three tombs were found in November 2023 during salvage operations in a northeastern district of the city. At some point, the tombs had been damaged by looting, but all three were relatively well preserved and included painted murals, decorations, inscriptions and epitaphs, the report said.

Related: Ancient Chinese tombs hold remains of warriors possibly buried alive

Two of the tombs are adorned with arches, doors, windows, figurines and floral patterns, as well as inscriptions with detailed information about people, events, history and geography at the time they were made.

The third tomb, however, is painted in a very different style. "Its chamber walls also imitate wooden structures, but the painted flora, fauna and colors are markedly different from the other two, leaving archaeologists room for further interpretation," the report said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Schneider said the differences in the styles of the tombs might be a sign that different cultures co-existed under the Jurchen Jin. She added that the rulers of the Jurchen Jin dynasty — also called the Golden Khanate, a name that indicated its non-Chinese origin — had descended from Tungusic-speaking seminomads from northeastern China. (Tungusic languages are spoken by peoples in parts of Siberia and northern China.)

"Their culture was very different from that of their Chinese subjects with regard to customs [like] eating habits, house styles, religion [and] social organization," Schneider said. "To take those differences into account, they ruled with two distinct administrative systems, one for their Chinese subjects and one for the Jurchen."

The Jurchen Jin rose to power amid rebellions against the region's Liao dynasty in the 12th century and fell to invading Mongols in the 13th century. They were also the ancestors of the Manchus, a later northeastern people who conquered China and Mongolia in the 17th century and ruled until the 19th century, Schneider noted.

However, nowadays, "Chinese official institutions and media are eager to show that Jurchen Jin tombs are 'Chinese,'" Schneider said. The report in China Daily reiterated this message, saying the tombs "reflected traditional Chinese culture, social ethics, ancient architectural characteristics, tomb architecture and funeral customs."

Viewing historically non-Chinese cultures as Chinese helps "to legitimize the territory of the PRC [People's Republic of China] today," she said.

"The discovery of non-Chinese findings is always tricky for Chinese officials as it shows that China has not always been China or Chinese," Schneider said. "This is a narrative the officials try to suppress."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.