Medieval warrior woman was buried alongside 23 Spanish monks, and no one knows why

A medieval woman who was buried alongside 23 warrior monks in Spain was likely a warrior herself, a new study finds.

While excavating a castle in Spain, archaeologists found a surprise: a woman buried alongside more than 20 medieval monks. And like the men, she was likely a warrior who died in battle, a new study suggests.

"We should picture her as a warrior of about forty years of age, just under five feet tall, neither stocky nor slender and skillful with a sword," study co-author Carme Rissech, a researcher in the Department of Basic Medical Sciences at the Public University of Tarragona, said in a statement. Researchers found human remains while excavating a cemetery within the fortified castle of Zorita de los Canes in Guadalajara. The burials date to between the 12th and 15th centuries, a time of complex religious and political conflict between Christian and Islamic groups in the Iberian Peninsula.

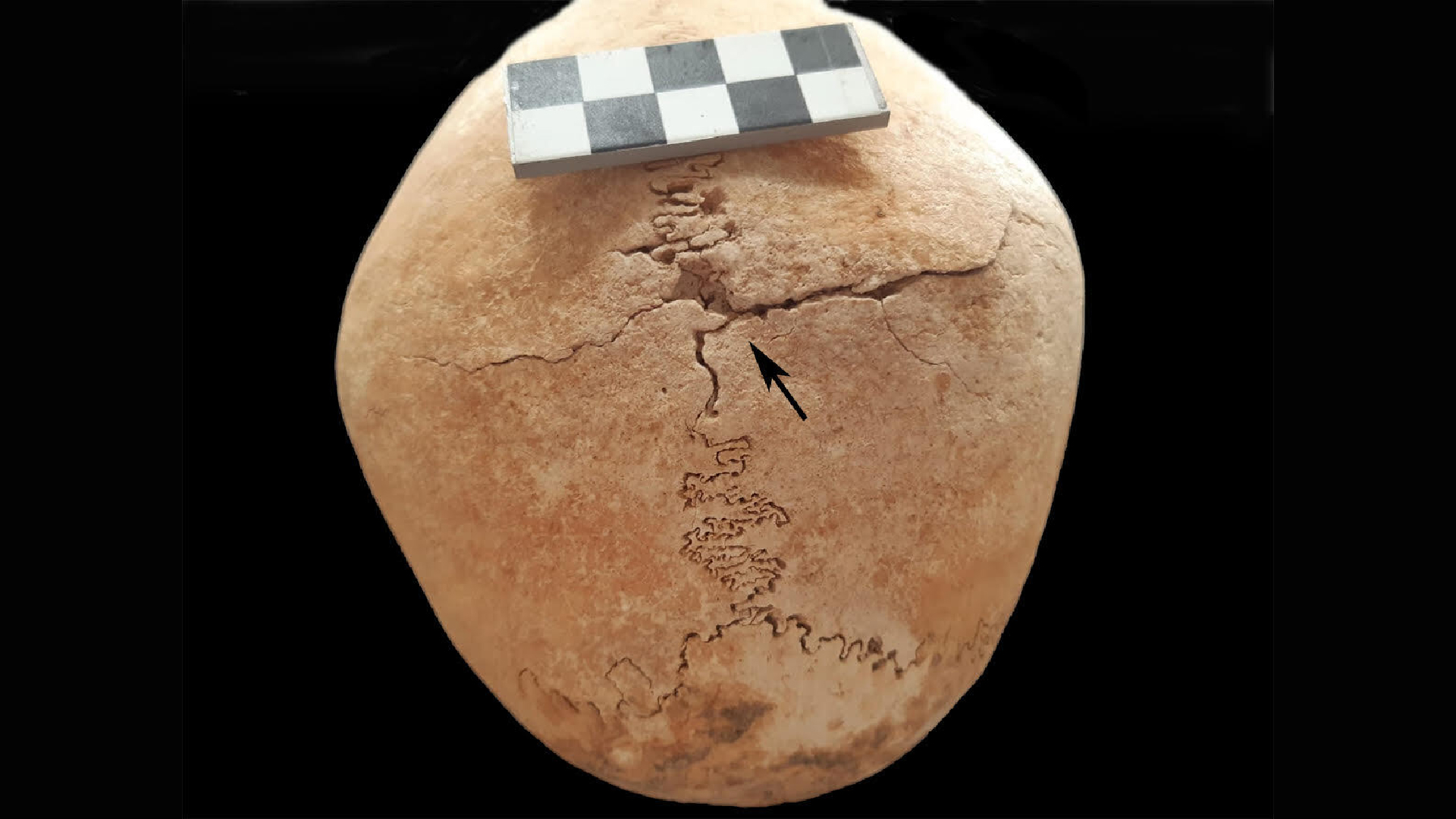

According to the study, published May 14 in the journal Scientific Reports, many of the skeletons display violent — even mortal — wounds, including a "significant number of penetrating stab wounds and blunt force injuries," to the skulls and pelvic areas, likely received in battle.

Based on an analysis of the woman's remains, it appears that she died in battle like the monks, as her bones show no signs of regrowth around her injuries. These particular warrior monks belonged to the Order of Calatrava, founded in Spain in 1158. This order, akin to the Knights Templar, was tasked with protecting Calatrava la Vieja, a city along the contested border between Christian and Muslim territories. In the 13th century, local nobility began supplying the order with money and men. For instance, many of the order's recruits, particularly higher-ranking knights and sergeants, were recruited from the lower nobility and urban leadership, the study noted. And although the knights of the Order of Calatrava took vows of poverty, they continued to feast like nobles, the study confirmed.

Related: Medieval girl buried face down with bound ankles, likely so she couldn't 'return' from the grave

The researchers established the warrior woman's sex by studying the pelvis and cranium, the two most common and reliable parts of the body for establishing biological sex.

By analyzing the different isotopes, or versions of nitrogen in the bones from Zorita de los Canes, the scientists also determined that the monks' diets were rich in poultry and marine fish, which were preferred by and affordable to Iberian social elites.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Heavy fish consumption suggests that the monks observed religious restrictions on meat, the study authors wrote.

Compared with the men, the woman ate far less protein, the isotope analysis showed. That suggests she probably came from a lower social class than the monks.

One hypothesis is that the woman was a servant in the castle and took up arms to protect it during battle, which ultimately led to her death. Her bones, however, show no wear and tear typical of servant labor. "I believe that these remains belong to a female warrior," Rissech said, "but further analysis is needed to determine to what extent this woman is contemporary with the other knights."

Hannah Kate Simon is an archaeologist and art historian with a focus on Roman art and archaeology. Hannah holds a Master's degree in the history of art and archaeology from New York University's Institute of Fine Arts, as well as two bachelor degrees in Art History and Theatre from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. She previously worked at NYU's Grey Art Gallery as a contributor to its exhibition catalogues, interned at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and excavated at Aphrodisias, an ancient Greek City in what is now Turkey.