Neanderthals: Who were they and what did our extinct human relatives look like?

Discover interesting facts about who Neanderthals were, whether they mated with modern humans and when they died out.

When they lived: 400,000 to 34,000 years ago

Where they lived: Western Eurasia, from Wales to Siberia to modern-day Israel.

What they ate: Meat, from elephants to mussels. Some also ate mushrooms, moss and even tree bark.

How big they were: 5'1" to 5'4" (1.50 to 1.75 meters) and 145 to 180 lbs (62 to 84 kilograms)

The Neanderthals were our closest human relatives, and roamed the Earth hundreds of thousands of years ago. Although they are long extinct, their genes still live in us today.

Neanderthals were hominins — a lineage that includes living humans (Homo sapiens) and our extinct relatives, as well as chimpanzees and bonobos.

H. sapiens last shared a common ancestor with Neanderthals somewhere between 600,000 and 800,000 years ago, though the exact date of the split is debated. Neanderthals arose as a distinct population between 400,000 and 350,000 years ago and went extinct around 34,000 ago. Neanderthals were closely related to another group of extinct, little-known human relatives called the Denisovans.

Everything you need to know about Neanderthals

What did Neanderthals look like?

Overall, Neanderthals looked a lot like us. If you saw one from behind, you would likely see a human form, perhaps a little on the short side, but walking perfectly upright. Yet once they turned around you’d start to see clear differences.

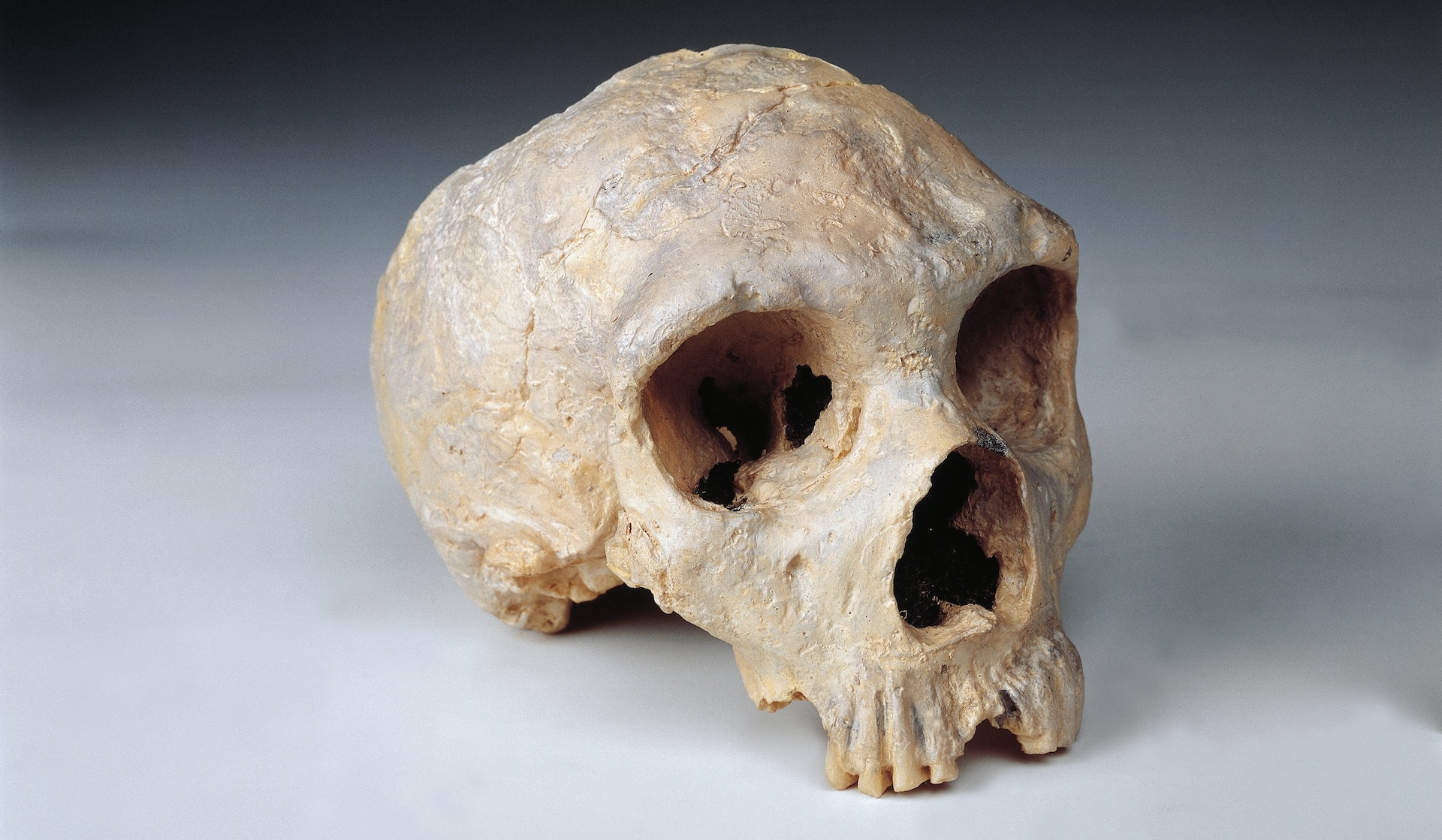

Although Neanderthal skulls and brains were large like ours, the shape differed: Their heads were long rather than globe-shaped and had lower foreheads and crowns. The internal structure of their brains was also different from ours. While researchers have zeroed in on more anatomical details that distinguish Neanderthals from H. sapiens, explaining exactly why they looked different remains tricky. Some features, such as their large rib cages or noses, might have not only have helped them thrive in the cold, but may also have helped fuel their physically intensive lifestyles.

Related: What's the difference between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens?

Were Neanderthals a different species from us?

Most experts agree that Neanderthals are a separate species from us. Neanderthal skeletons have both obvious and subtle differences from those of H. sapiens, leading scientists in 1864 to assign them the species name Homo neanderthalensis. Modern analysis of ancient DNA shows that Neanderthals mated with ancient Homo sapiens and produced fertile offspring. But other closely related animal species, such as polar and brown bears, can also produce fertile offspring, so this is not sufficient to classify creatures as part of the same species.

Related: Are Neanderthals and Homo sapiens the same species?

Could Neanderthals talk?

Researchers largely agree that Neanderthals communicated vocally, but whether they had language remains a hot topic. Their internal ear anatomy suggests speech of some sort was important in their everyday lives, and they could probably make a similar range of sounds as we do. However, they may not have used the complex language we do. One expert suggested that Neanderthals may have talked at the level of a typical 3-year-old, which means they may have been able to describe color, shape and number, but would struggle to tell complex narratives or use verbs that convey past, present and future.

But they may have used recognizable gestures during social interactions, just as we and our close relations, the chimpanzees do, according to 2023 study.

Genetic studies showed Neanderthals also carried the FOXP2 gene, which appears key in human language ability. But their version worked slightly differently from ours.

There's still a lot of speculation about Neanderthal speech, which means we cannot yet draw clear conclusions about the complexity of Neanderthal speech.

Related: Could Neanderthals talk?

Why did Neanderthals go extinct?

Neanderthals vanished as a distinctive type of hominin around 40,000 years ago. Exactly why remains a big question.

Climate is a key suspect. Many studies, including one published in 2022 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, have found that rapid climate change affected the environment and prey animals of Neanderthals in the final 10,000 years of their existence. Yet Neanderthals had previously survived unstable climate extremes without dying off.

Others suggest that when H. sapiens arrived into Eurasia, our ancestors competed with Neanderthals for habitat and prey, or possibly even fought directly with them. However, more recent research has shown that early populations of our species were already present in Eurasia at least 100,000 years earlier than previously thought. What’s more, we have no archaeological evidence of conflict between modern humans and Neanderthals.

More likely, many factors led to the demise of the Neanderthals. They had relatively small and isolated communities which led to inbreeding and low genetic diversity. So they may have been at higher risk of "slow motion" extinction, two 2019 studies suggest. The real "end" of the Neanderthals was probably more a quiet ebbing away than a dramatic finale.

And 2024 study in the journal Science found that up to 3.7% of the Neanderthal genome came from modern humans. That, in turn, suggests a picture in which Neanderthals didn't die out per se, but were rather absorbed and assimilated into our own modern human population, ending their journey as a distinct lineage.

Related: The mystery of the disappearing Neanderthal Y chromosome

Did humans and Neanderthals mate?

Neanderthals and modern humans definitely mated during at least three periods, and traces of those long-ago couplings linger in our genome today. A 2010 study in the journal Science provided the first DNA evidence of our ancestors mating with Neanderthals. A 2014 study suggests up to 50% of the original Neanderthal genome might be preserved, but spread into different sections across all humans living today. For people not of sub-Saharan ancestry, the most recent analyses suggest around 1% to 2.4% of their DNA originally came from Neanderthals. But even people of sub-Saharan ancestry have some Neanderthal DNA, which they probably gained when humans from Eurasia migrated much later into Africa.

Neanderthal genes in living people seem to have come from one phase of mating around 55,000 to 60,000 years ago, yet we know from DNA in Homo sapiens fossils that mating was happening earlier and later too, around 40,000 to 45,000 years ago, just before Neanderthals went extinct. Genetic data from much older Neanderthal fossils also tells us that far more ancient encounters also took place with Homo sapiens between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago, yet those periods of mating left no descendants alive today.

Scientists have compared the DNA of Neanderthals with that of modern humans to better understand how genes from Neanderthals affect living humans today. Some of the most strongly retained genes related to immunity, which makes sense as the resistance Neanderthals had built up to local Eurasian viruses and bacteria over 300,000 years would have been useful to H. sapiens people entering the continent for the first time. Additionally, a different genetic legacy from Neanderthals appears to promote fertility and protect against miscarriage.

Related: 'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors

Yet other effects can be subtle. For example, a 2018 study found that people with particular Neanderthal gene variants show some differences in brain shape, but not enough that you would notice when meeting them. Neanderthals also gave us certain genes that affect our circadian clock, which may help explain why some of us are early risers.

Some of what was perhaps historically useful may have negative impacts today. For instance, one Neanderthal genetic variant makes people today more sensitive to pain, which could lead to more rapid aging. And Neanderthal DNA is strongly linked to "Viking's Disease," or Dupuytren's contracture, where fingers get curved and frozen in place. Our extinct human relatives also gave us genes that increase the risk of lupus, Crohn's disease and other autoimmune disorders.

One particular Neanderthal genetic variant makes people twice as likely to become severely ill from COVID-19; if they inherit two copies, the risk is even higher. However, the picture here is complex. A different Neanderthal gene offered protection against severe COVID-19.

Related: 10 unexpected ways Neanderthal DNA affects our health

Glossary

- Homo Neanderthalensis - the scientific name for Neanderthals. They were named after the Neander Valley, where some of the first bones were found in 1856.

- Denisovan - an extinct human relative of both Neanderthals and modern humans that lived across Asia. They are named after Denisova Cave in Russia, where the first finger bone was found.

- Hominin - the lineage that includes modern humans and our extinct relatives, including Neanderthals, as well as bonobos and chimpanzees.

- Homo sapiens - The scientific name for modern humans. While Homo sapiens interbred with Neanderthals, most scientists think they were still a different species from us.

- Gene variant - A difference in the sequence of DNA "letters" that make up a gene. Modern humans inherited certain gene variants from Neanderthals.

Neanderthal pictures

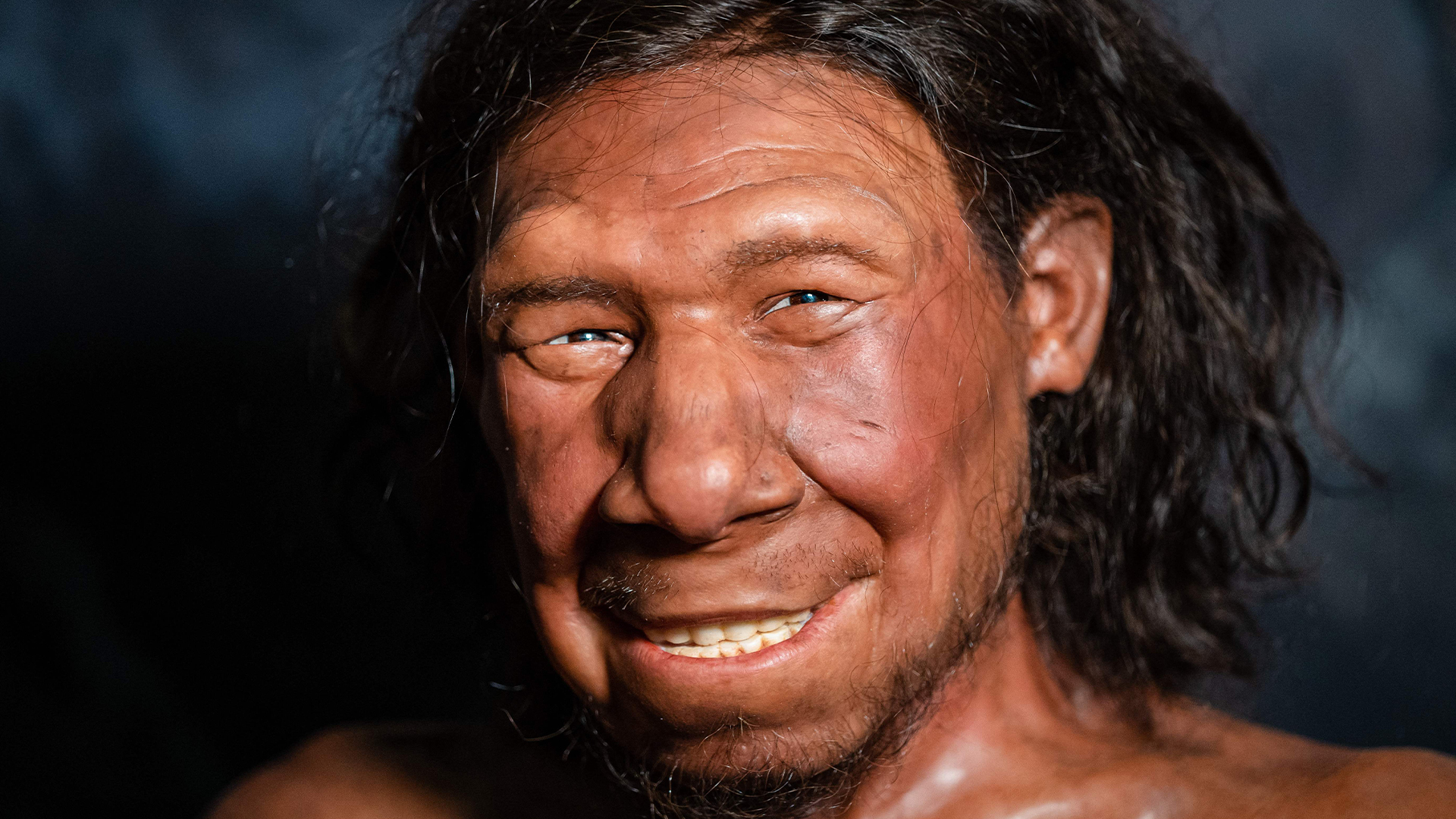

The large noses of Neanderthals, as seen in this reconstruction of the oldest Neanderthal found in the Netherlands, may have been an adaptation to their cold environment or physically demanding lifestyle.

Study researchers Trine Freiesleben and Jean-Claude study Europe's oldest engravings in a French cave likely made by Neanderthals as long as 75,000 years ago.

A digital graphic comparing a Neanderthal cranium and ear with that of a modern human.

A reconstruction of a Neanderthal man at the human evolution exhibit at the Natural History Museum in London, United Kingdom.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rebecca Wragg Sykes has studied Neanderthals for twenty years. In addition to her academic work as an Honorary Fellow at the University of Liverpool in the U.K., she is widely recognized for her public scholarship in science communication, through writing, broadcast and consultancy. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, the Times and The Guardian, among others. Her first book, "Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art" won the 2021 PEN Hessell-Tiltman prize for history and was listed in the New York Times' 100 Notable Books. In 2022 she received the Royal Anthropological Institute's Public Anthropology Award, and the President's Award from the Prehistoric Society. She is currently writing her next book, Matriarcha: Prehistory Re-imagined.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.