No one 'expected to find what we did': 4,000-year-old Canaanite arch in Israel may have been used by cult

Archeologists discovered the mysterious arch at the end of a narrow, underground passageway that was sealed with sediment shortly after it was built in the Middle Bronze Age.

Archaeologists in Israel have unearthed a mysterious Canaanite arch and vaulted stairway sealed inside a well-preserved mud brick building that dates to 3,800 years ago, during the Middle Bronze Age. The archaeologists have no idea why the arch was built.

The team had previously excavated a long corridor leading to the arch and stairway at the archaeological site of Tel Shimron, but they were blown away by the preservation of the newfound structures, calling them "breathtaking, especially since the building material is unfired (!) mud brick — a material that only rarely survives a long time," Mario A.S. Martin, co-director of the excavation at Tel Shimron and an archaeologist at the University of Innsbruck in Austria, told Live Science in an email.

"Of course you never know what you find at a site that has never been excavated, but I can say with confidence that nobody … expected to find what we did," Martin added.

The arch is corbelled, meaning the vault was created by offsetting bricks like an inverted staircase rather than with wedge-shaped stones, which are typically used to build "true" arches. This so-called "false" arch and stairway stands more than 16 feet (5 meters) tall and includes around 9,000 bricks, Martin said.

The ancient Mesopotamins are known for using bricks to make such corbelled construction, but it's never been found in the southern Levant, the region east of the Mediterranean, from this time, he said.

Not long after the corridor and stairway were built — only about one or two generations — ancient workers backfilled both with sediment. However, it's unclear why these structures were sealed off, and it deepens the mystery as to why the Canaanites erected it in the first place.

"Why the passage went out of use so soon is a matter of speculation, fact is that it was done with full intent, and not because there was some imminent danger of collapse," Martin said. "For us archaeologists, the quick backfill is the most lucky piece of the whole story, since it is the only reason the feature is so incredibly well preserved almost 4,000 years later."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: Blood-red walls of Roman amphitheater unearthed near 'Armageddon' in Israel

The Canaanites lived in the southern Levant between 3,000 and 4,000 years ago. There is no evidence to suggest the Canaanites were ever united politically or ethnically as a single kingdom, Ann Killebrew, an archaeologist and associate professor at Penn State University, wrote in her book "Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, And Early Israel 1300-1100 B.C.E." (Society of Biblical Literature, 2005).

"Canaan was not made up of a single 'ethnic' group but consisted of a population whose diversity may be hinted at by the great variety of burial customs and cultic structures," Killebrew wrote.

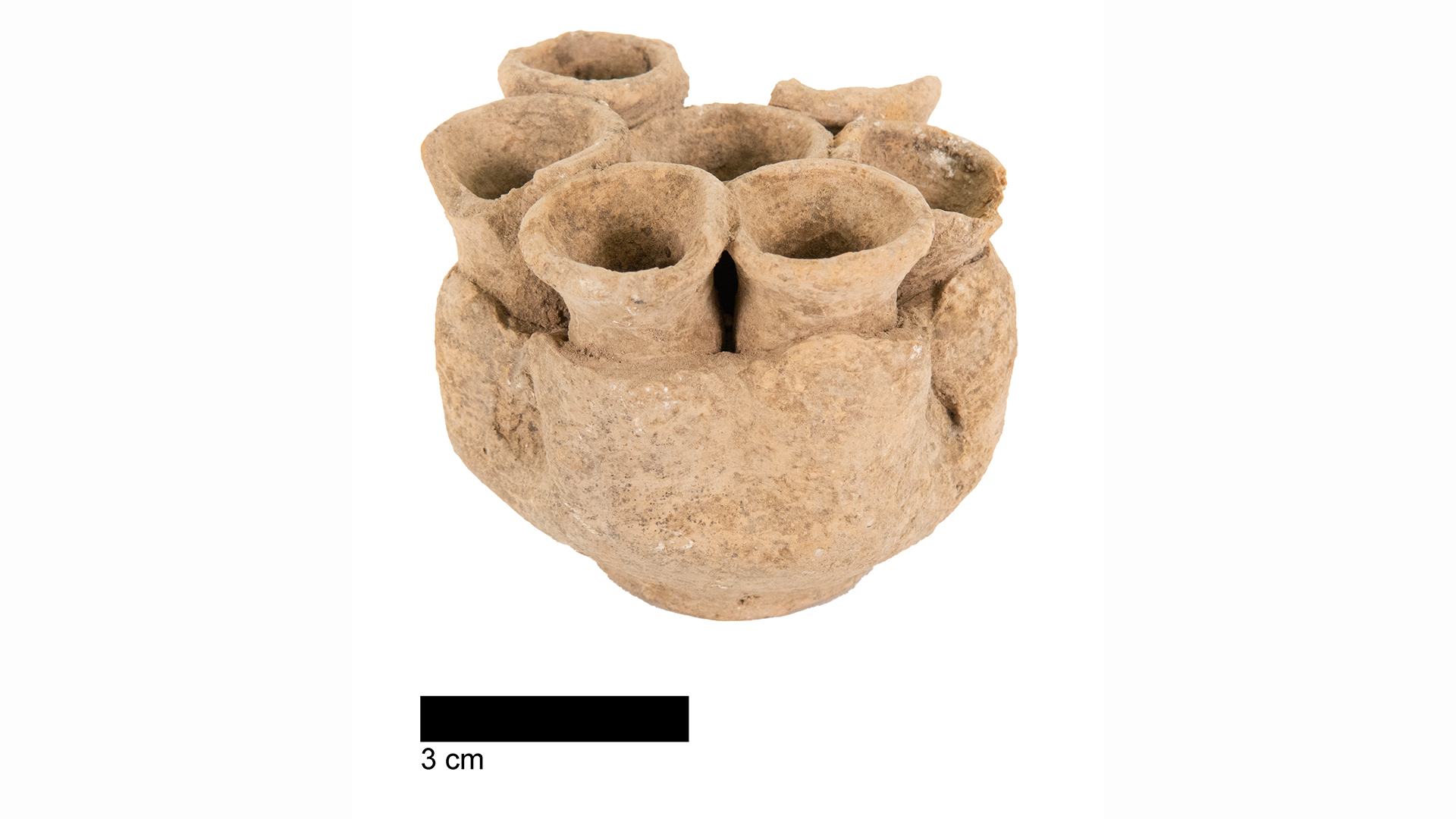

The newly excavated building, which sits within the ancient acropolis of Tel Shimron in the fertile Jezreel Valley, may have served a cultic function, archaeologists told the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. Inside the passageway and before a sharp left turn that leads to the monumental arch, they discovered a seven-cupped pottery artifact known as a Nahariya bowl, which was used for ritual offerings in the Middle Bronze Age.

Other clues hint at cultic traditions within Tel Shimron, which sprawled across the top of a hill and was surrounded by massive ramparts during its heyday. Previous excavations of another mud brick structure within the acropolis uncovered 30,000 bones belonging to animals that were likely sacrificed, the archaeologists said.

Having dug their way past the arch, archaeologists came upon stairs leading deeper underground and beyond the building's walls. The stairway could take years to excavate, they said, because it likely extends beneath other fragile Bronze Age ruins that might collapse if they remove the soil.

"We will only understand the full significance of the corridor and the vaulted passageway (and where it exactly leads to), once we excavate more of the environs and beyond the blocked staircase," Martin told Live Science.

Until they find a way to safely excavate the enigmatic stairway, archaeologists have reburied the passageway and arch to protect them from damage.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

- Laura GeggelEditor