Oldest sinew bowstrings ever found in Europe have been hiding in Spain's 'Bat Cave' for 7,000 years

The bowstrings were found with wood-and-reed arrows and were used by the first European farmers.

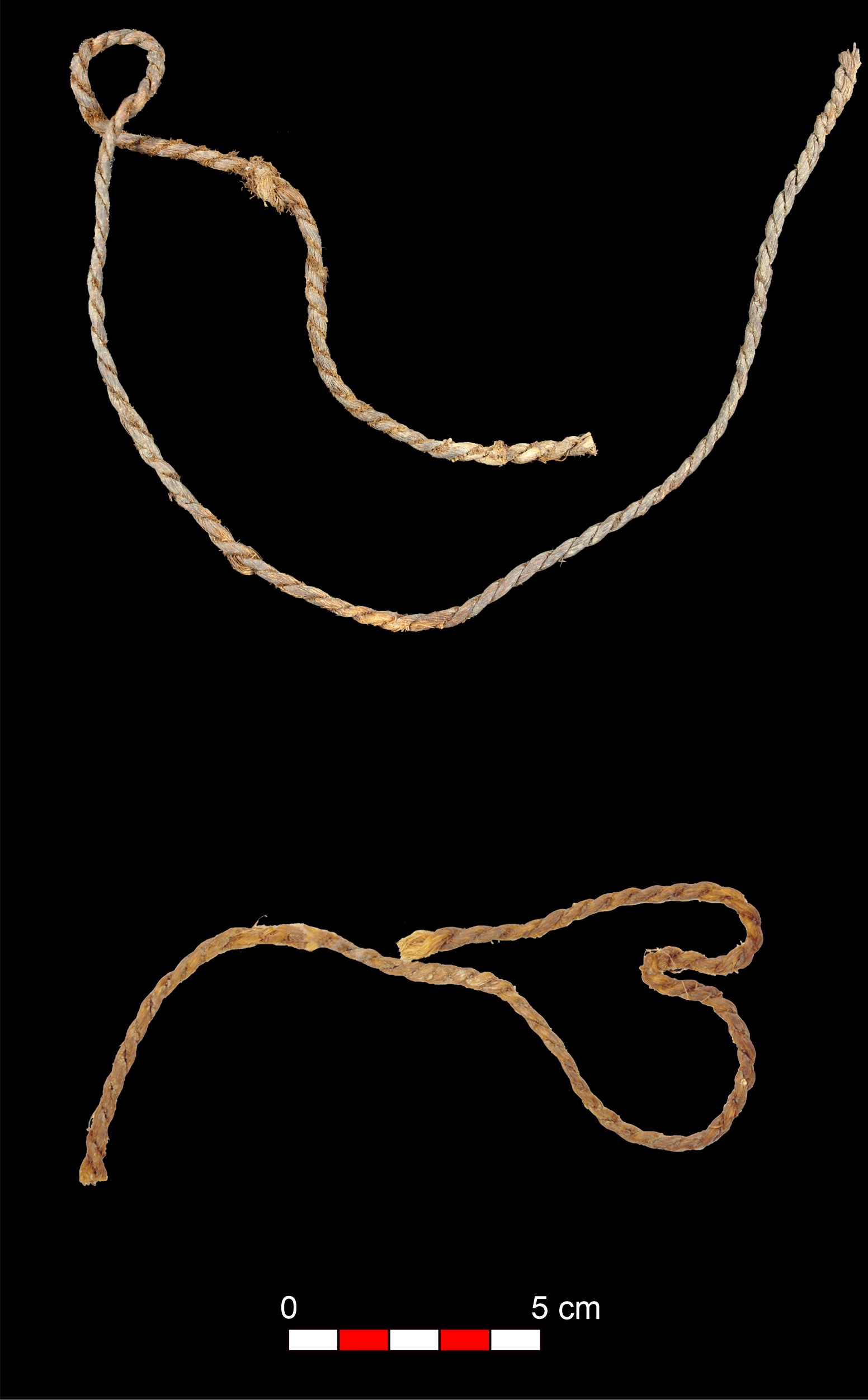

Roughly 7,000-year-old cords found in a stunning Spanish cave are Europe's oldest bowstrings made of sinew, new research finds.

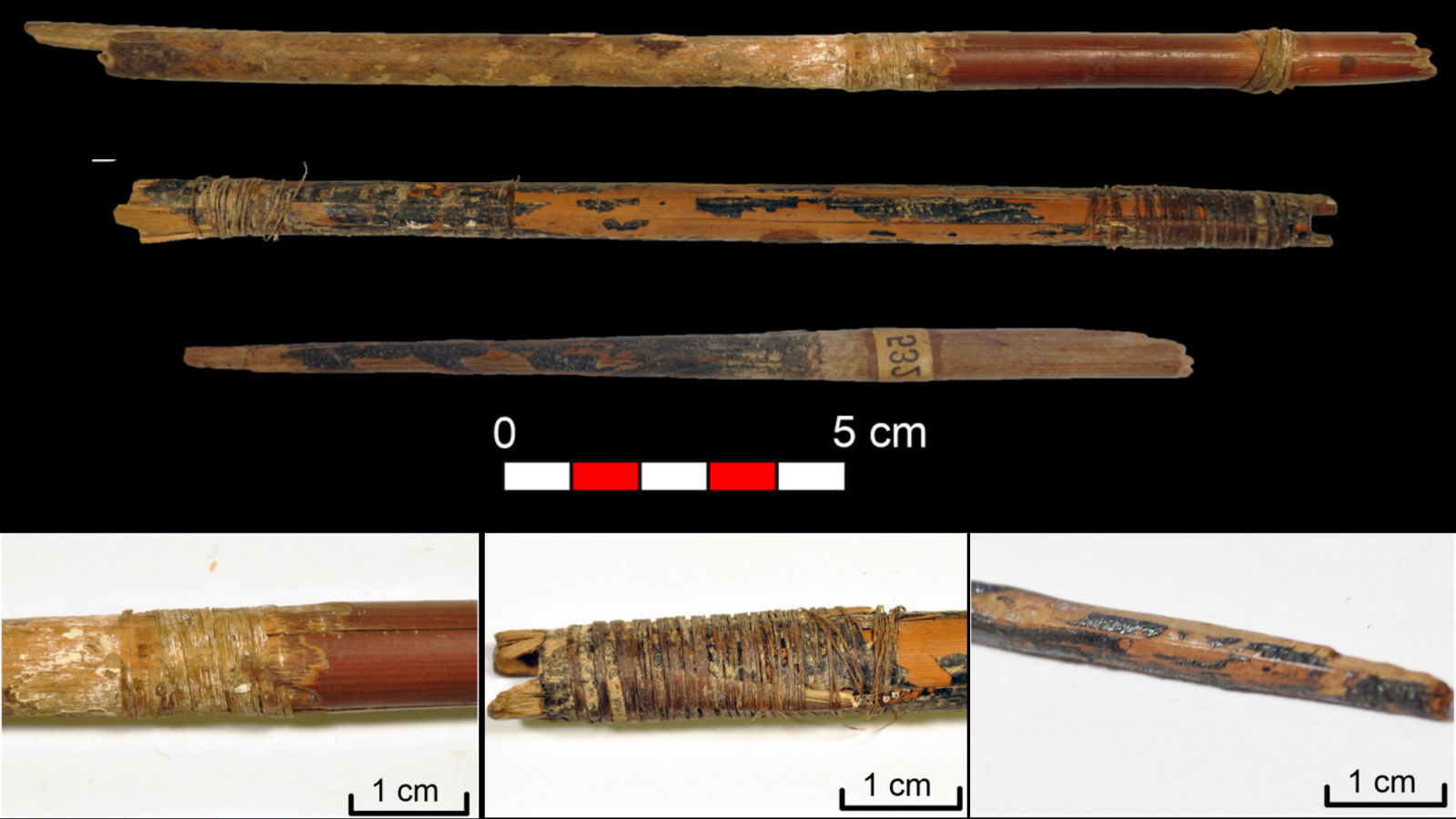

The bowstrings — along with fragments of wood-and-reed arrows, one with two features still affixed — date to the early Neolithic, when ancient Europeans first began farming. They're at least 2,000 years older than the next-oldest known bowstrings made from animal products in Europe, which were found near the famous ice mummy Ötzi in the Italian Alps.

The new find reveals that Ötzi's bow-and-arrow technology was not new to Europeans, study lead author Ingrid Bertin, a doctoral student in archaeology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona in Spain, told Live Science.

"They look the same," she said. "They're twisted in the same way, there is the same distance between the twists, and it's really impressive because it is the technique that is still used nowadays."

The bowstrings come from Cueva de Los Murciélagos, or "Bat Cave," an extensive, stalactite-studded cave system in Albuñol, a town in the province of Granada. In the 1800s, miners in the cave discovered artifacts and human remains within the cave. There were no archaeologists around, Bertin said, so the items ended up scattered; most of the human remains have been lost. In the 1860s, an archaeologist at the University of Granada did his best to gather everything found in the cave and split the collection between the Archaeological Museum of Granada and the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid. Later studies found that the items date to the late sixth and early fifth millennium B.C.

Related: 65,000-year-old hearth in Gibraltar may have been a Neanderthal 'glue factory,' study finds

More recently, researchers began new excavations to see if any material still lay in place in the caves. They found, among other things, a cord — perhaps a bowstring — that dated to the Bronze Age, between 1960 and 1754 B.C. The researchers decided to try gathering all evidence of archery in the cave to analyze it fully. They used radiocarbon dating to understand the materials' age and protein and lipid analysis to learn what the items were made of.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team ended up discovering two groups of items — one from the Bronze Age and one far, far older. The Bronze Age items included the newly discovered bowstring, as well as a maple arrow shaft with a spiral decoration. The early Neolithic people who used the cave left behind a whole treasure trove of items, including a reed shaft attached to a willow-wood arrowhead connected with adhesive and fibers, a reed arrow shaft with two tied-on feathers — the oldest known European fletched arrow — and a wooden point made of an olive twig. One of the bowstrings was also from this era, making it among the oldest bowstrings ever in Europe and the oldest made of animal materials.

The analyses showed that these ancient archers used birchbark tar as a glue and the sinew of multiple animal species twisted together for bowstrings. They were able to identify one species, the roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). Other species may have included wild boar, goat or ibex. Prior to this study, the only early Neolithic bowstring found in Europe — a cord from a site called La Draga in Spain — was made of nettle, not animal sinew. Archery is far older, though, with stone points suggesting that ancient Europeans were making bows and arrows in the Stone Age 54,000 years ago.

"It's amazing, really, to work with this kind of material in a site where everything is so well preserved," Bertin said. The team is now working to find out if they can detect ancient human DNA in the birchbark tar, which might reveal more about the people who made and handled the arrows.

The arrows could have been used for both hunting and warfare, Bertin said. Although the people who used the caves were certainly farmers and herders, the wild-animal materials found with the human remains indicate that they still hunted, too. And cave drawings and carvings from the region sometimes depict groups in battle, aiming arrows at one another.

"Now what we'd like to find," Bertin said, "is to see if there is a bow that is found in the cave."

The findings were published Dec. 5 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.