Origins of world's earliest writing point to symbols on 'seals' used in Mesopotamian trade

Researchers investigating how the first writing arose identified the motifs on preliterate "cylinder seals" used in the trade of agricultural products and textiles.

The world's oldest known system of writing was influenced by symbols used for trade — engravings found on cylinders used in the exchange of farming produce and textiles, a new study suggests.

The finding reinforces an idea proposed in earlier research: that cuneiform script — which was developed in early Mesopotamia around 3100 B.C. and is thought to be the earliest writing system — originated in part from accounting methods for tracking the production, storage and transport of such items.

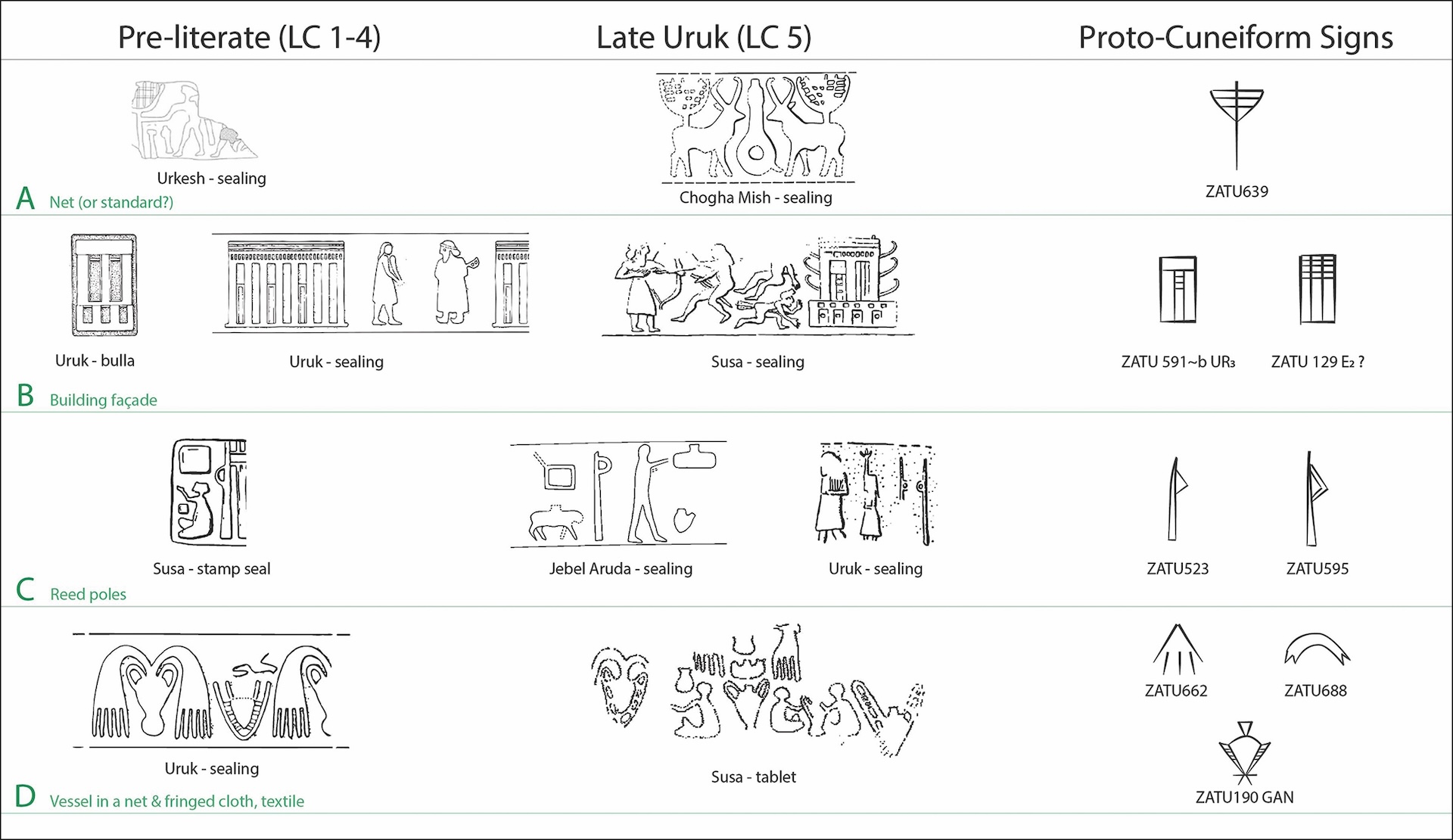

According to the researchers, several symbols engraved on stone "cylinder seals" were developed into signs used in "proto-cuneiform," an early version of the cuneiform script used in southern Mesopotamia, now southern Iraq. The researchers reported their findings in a study published Tuesday (Nov. 5) in the journal Antiquity.

Such cylinder seals were used for millennia throughout Mesopotamia, where they were rolled across clay tablets to print their motifs on them — often to verify a transaction or, later, a letter.

Some of the seals examined in the new study date to about 4400 B.C. — more than 1,000 years before the development of writing. "We focused on seal imagery that originated before the invention of writing, while continuing to develop into the proto-literate period," study co-authors Kathryn Kelley and Mattia Cartolano, both researchers in the Department of Classical Philology and Italian Studies at the University of Bologna, said in a statement.

Related: 'A king will die': 4,000-year-old lunar eclipse omen tablets finally deciphered

The team's work identified seal motifs related to the transport of jars and cloth between different Mesopotamian cities, probably involving temple institutions. The researchers suggest these motifs became proto-cuneiform signs in early writings about the trade of farming produce and textiles.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The discovery, which still has skeptics, shows the continuity between the "preliterate" seals and early writing, according to the authors.

"It proves that the motifs known from cylinder seals are directly related to the development of writing in southern Iraq and shows how meaning was transferred from preliterate motifs into script," they wrote in the statement.

Oldest writing

Cuneiform writing used a stylus to make wedge-shaped impressions in unbaked clay. These impressions created signs representing sounds to make a record of spoken language. The clay could be dried or baked, preserving the signs.

Cuneiform was developed by the Sumerian civilization that lived in early cities in southern Mesopotamia from about 5500 to 2300 B.C., when it was succeeded by the Akkadian Empire, based in the city of Akkad.

The Akkadians adopted the Sumerian system of writing but applied it to their own language — and Akkadian written in cuneiform became the common written language of Mesopotamia for more than 2,000 years, throughout the subsequent Babylonian and Assyrian periods.

The new study highlights several motifs seen on preliterate cylinder seals. The authors suggest these motifs were developed into signs in the proto-cuneiform script seen on 5,000-year-old clay tablets from the southern Mesopotamian city of Uruk. These include symbols depicting a building, poles made from reeds, and fringed cloths in a vessel.

The authors hope their work will help scholars decode more proto-cuneiform symbols, as well as provide insight into the meaning of some seal motifs.

"The conceptual leap from pre-writing symbolism to writing is a significant development in human cognitive technologies," study co-author Silvia Ferrara, a professor in the Department of Classical Philology and Italian Studies at the University of Bologna, said in the statement. "The invention of writing marks the transition between prehistory and history, and the findings of this study bridge this divide by illustrating how some late prehistoric images were incorporated into one of the earliest invented writing systems."

Unclear origins

Anthropologist Gordon Whittaker, an expert on the origins of cuneiform at the University of Göttingen in Germany who was not involved in the study, called it "interesting and thought-provoking." But he cautioned that it may be premature to suggest the motifs on cylinder seals were "stimuli for the invention of writing."

"In the few instances in which the same item appears to be depicted in both a seal and a proto-cuneiform sign, there is no obvious causal relationship that would link the one with the other," he told Live Science in an email.

"Furthermore, several of the shapes — such as a narrow oblong without internal detail — are simply too general or vague to be helpful to the authors' argument," he said.

University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Holly Pittman, who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email that the new study verified her suggestion from roughly 30 years ago, that the imagery on seals was a fundamental influence on proto-cuneiform writing.

Pittman said the idea was dismissed at the time, but she was pleased to see that the authors of the new study had reached the same conclusion.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.