Ötzi the Iceman used surprisingly modern technique for his tattoos 5,300 years ago, study suggests

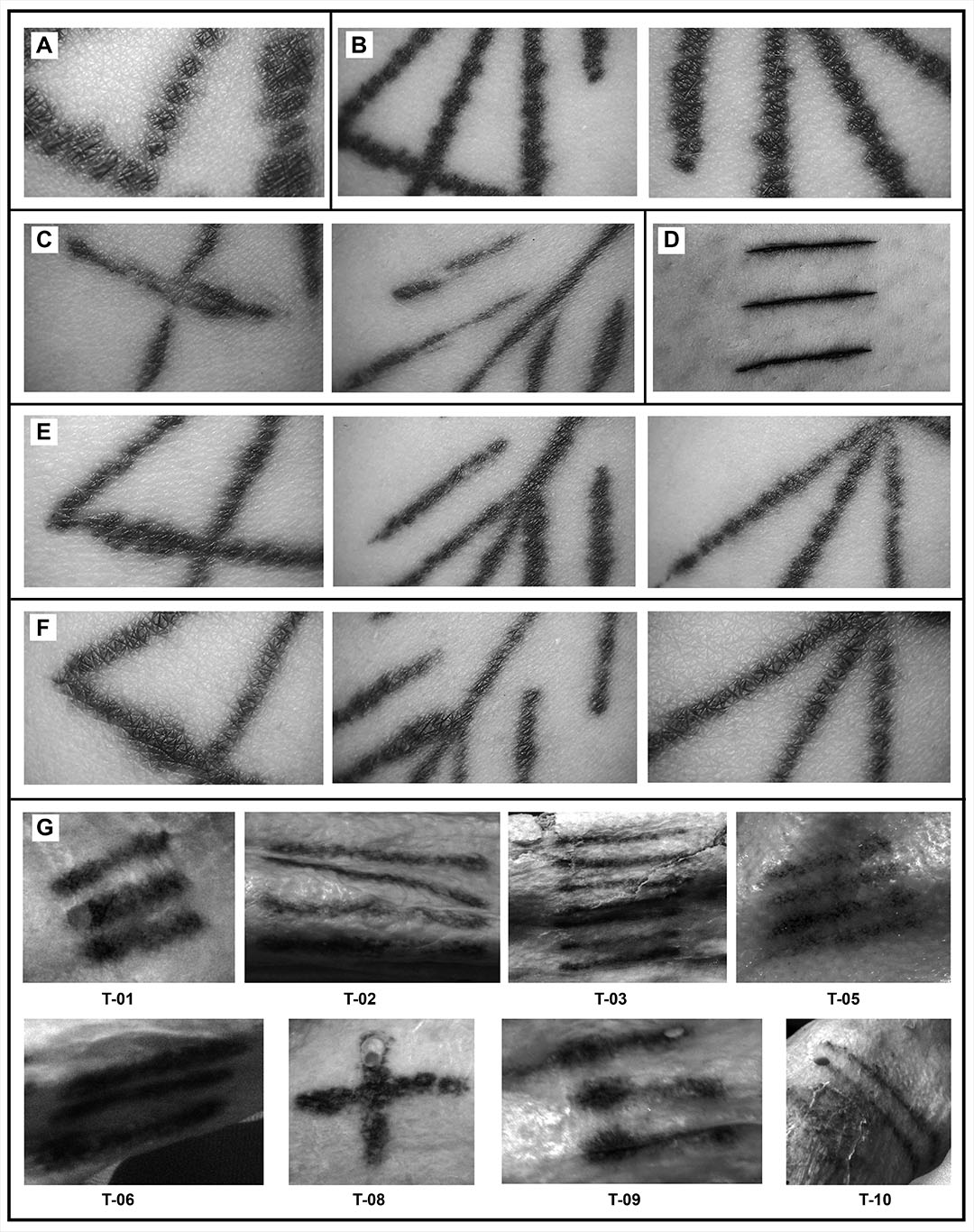

The researchers compared Ötzi's ancient tattoos with modern tattoos made using different techniques on the skin of one of the authors.

Ötzi the Iceman's many tattoos were made by "hand-poking" — a manual version of the tattooing technique usually used today — and not by cutting his skin as some researchers have suggested, according to a new study.

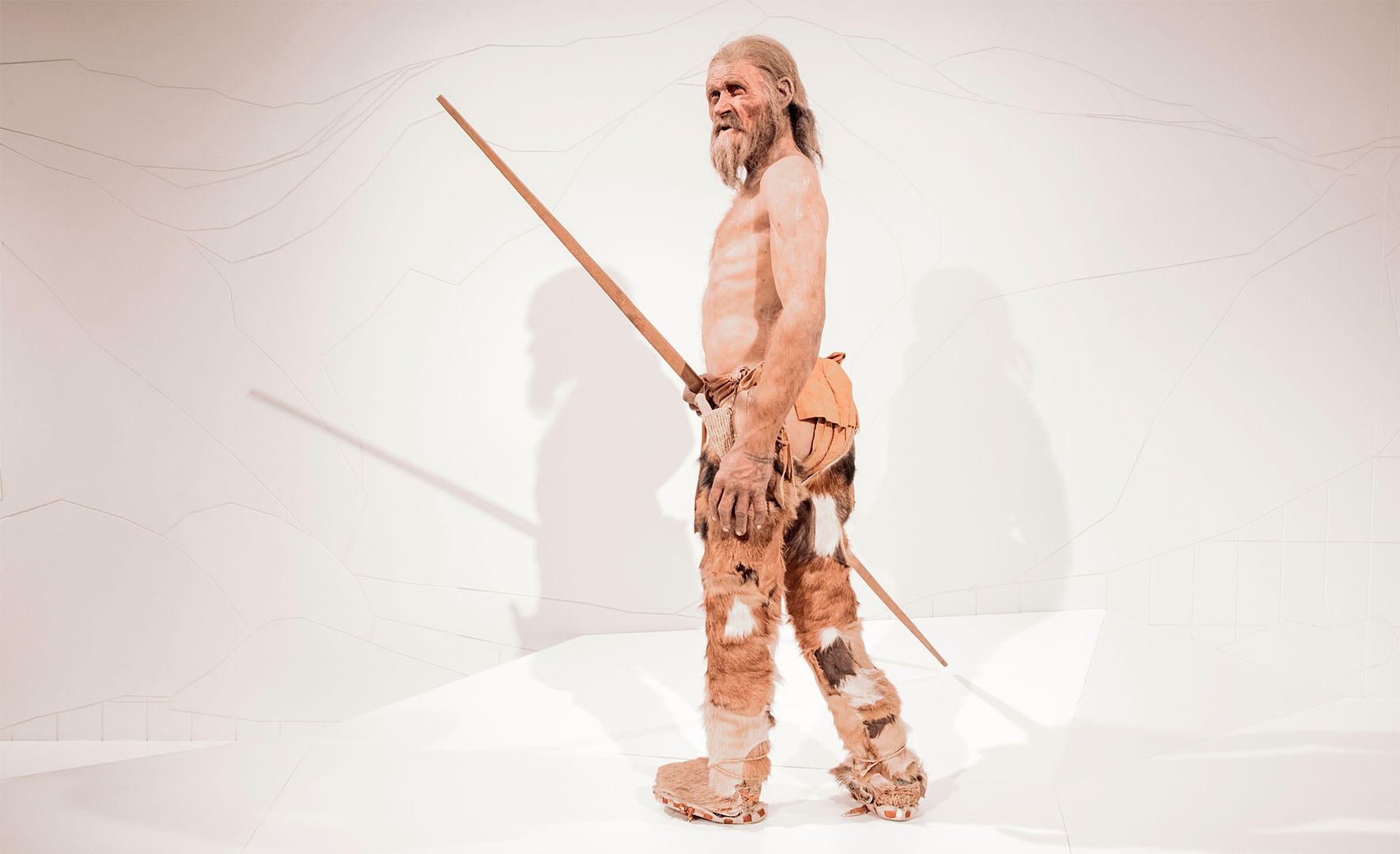

Ötzi died in Europe's Alps about 5,300 years ago, and his body remained mummified there for thousands of years until tourists discovered it in 1991 on a mountain pass near the border of Italy and Austria. Studies have since revealed many aspects of his life, including the tools and weapons he carried, his clothes and his last meal.

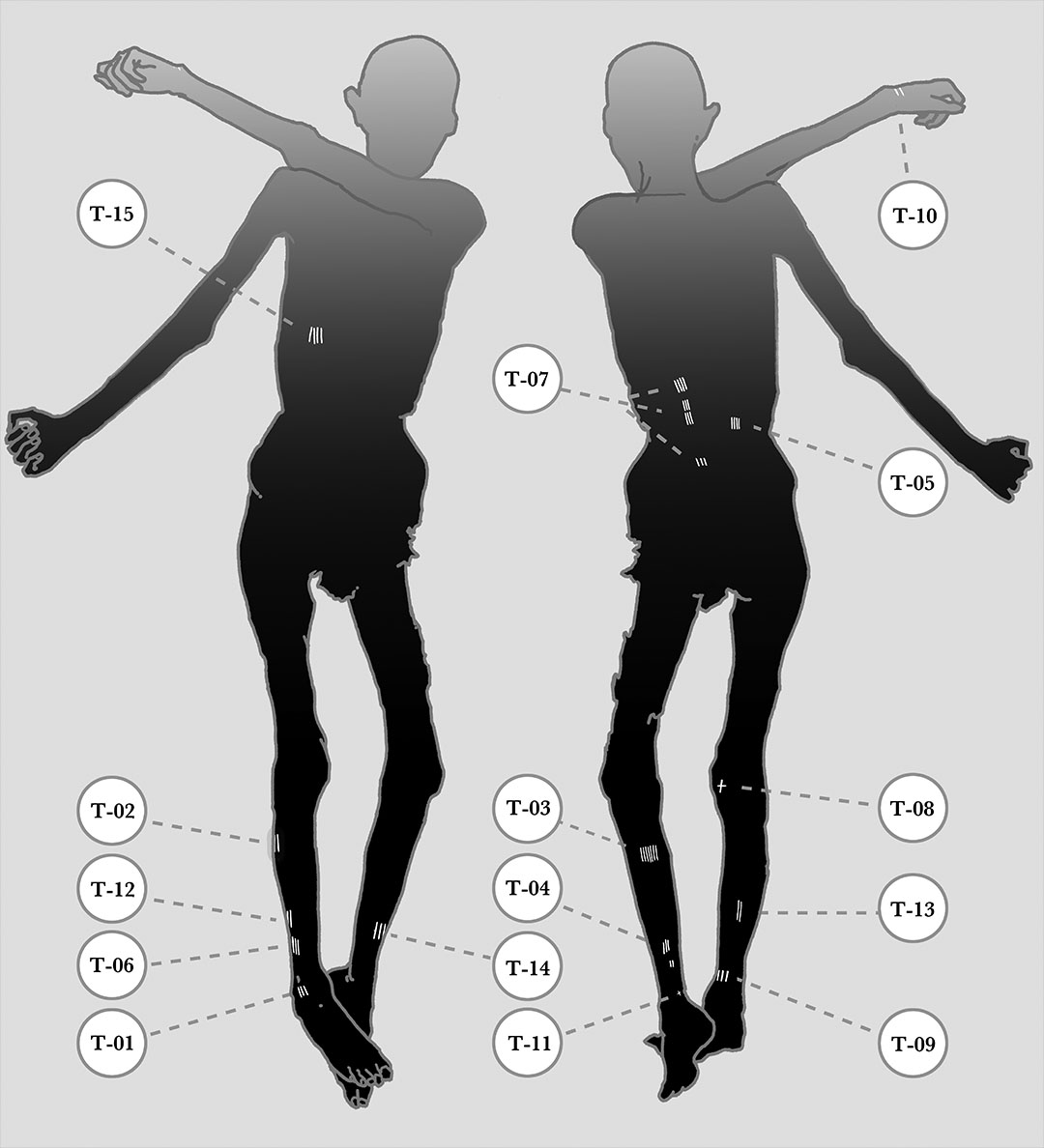

There have also been studies of Ötzi's 61 tattoos; but while it's often reported they were made by cutting the skin and rubbing soot into the incision, that doesn't seem to have been the case, according to study first author Aaron Deter-Wolf, an expert on ancient tattooing who works for the state of Tennessee's Department of Environment and Conservation.

Instead, "within reasonable doubt they are hand-poked, rather than being incised or being done in any other style," Deter-Wolf told Live Science.

Hand-poking involves piercing the skin with an awl or needle and has some similarities to modern tattooing machines, according to the study, published on March 13 in the European Journal of Archaeology.

Related: Ötzi the Iceman may have been bald and getting fat before his murder 5,300 years ago

Experimental tattooing

In the new study, the researchers compared Ötzi's tattoos to modern tattoos made on human skin, which were created and detailed as part of a 2022 study investigating pre-modern tattooing techniques.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Those included tattoos made by hand-poking, by incisions, by tapping points with a mallet — traditionally used throughout the Pacific region — and by subdermal tattooing, which can use a pigmented thread to "stitch" the skin and was commonly performed by Inuit peoples.

The modern tattoos were made on the leg of Danny Riday, a professional tattoo artist in New Zealand and a co-author of both the 2022 study and the latest study.

The comparison indicated that none of Ötzi's tattoos were formed from incisions, which create narrow lines at the ends where the healing skin pulls the cut closed, Deter-Wolf said. But Ötzi's tattoos matched the "hand-poked" tattoos, in which a pigment — black soot, in Ötzi's case — is retained within the tiny piercings in the skin.

Deter-Wolf said the shape of hand-poked tattoo lines depended on the shape of the tip used, and Ötzi's tattoos seem to have been made by an awl — a tool for piercing holes in leather, typically a little larger than the holes made by a needle.

It may be that tattooing awls have been misclassified as regular tools at other archaeological sites, he said.

Tattooing for medicine

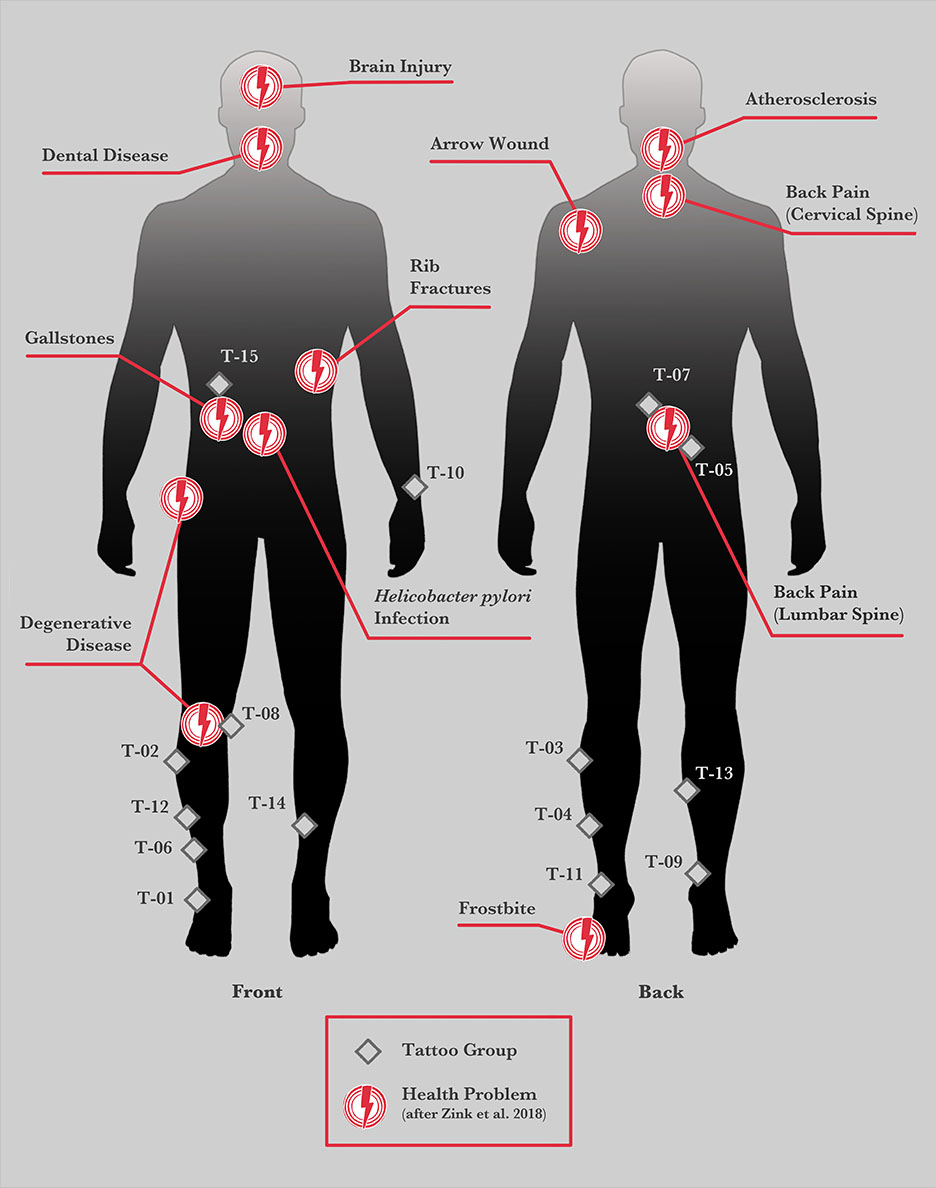

Ötzi's tattoos have no obvious symbolism, unlike some ancient Peruvian and Scythian tattoos; and earlier studies suggested that many of Ötzi's tattoos may have been therapeutic — that is, intended as medical treatments.

But many of Ötzi's tattoos depict stacked parallel lines and plus-sign-like marks, and Deter-Wolf said that any — or none — of them may have had some unknown symbolism. He noted that most of Ötzi's tattoos would have been covered by his clothing, but a tattoo like a bracelet on his left wrist would have been visible.

Scientific conservator Marco Samadelli, who studies Ötzi's remains at Italy's Institute for Mummy Studies in Bolzano, near where they were found, said that the new study was of a "high scientific standard."

He told Live Science in an email that "the authors do not claim with absolute certainty the puncture tattoo technique with a single-pointed instrument, but give extensive and plausible explanations."

Samadelli wasn't involved in the latest study but has led rigorous research into Ötzi's tattoos. He favours the idea that many or most of Ötzi's tattoos were made for therapeutic purposes.

"The fact that not all the tattoos are placed at [the locations of] wounds or diseases does not mean that they must therefore have a symbolic meaning, but that their correlation has probably not yet been identified," he said.

Editor's note: Updated at 2:53 p.m. EDT to note that Marco Samadelli is a scientific conservator, not as archaeologist as was previously stated.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.