Paleo-Arabic inscription on rock was made by Prophet Muhammad's companion before he converted, study finds

The writing is only the second confirmed inscription whose attribution connects to Muhammad.

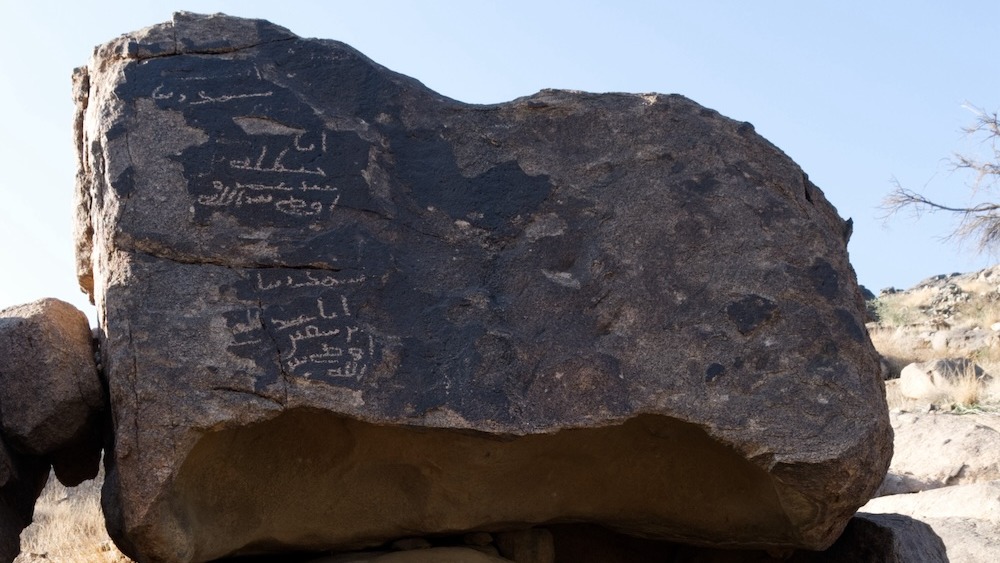

A Paleo-Arabic inscription on a boulder near an abandoned mosque in Saudi Arabia may have been carved by Ḥanẓalah bin Abī ʿĀmir, a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, a new study finds.

Although many inscriptions from the early days of Islam are known, their authorship remains unconfirmed, except for one in Saudi Arabia's al-Bahah region that can be securely attributed to Muhammad's companion, who later became the governor of Mecca. The inscription, which researchers analyzed in a new study published in the April issue of the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, is only the second confirmed inscription whose attribution connects to Muhammad. Unlike the former text, this one was carved in the early seventh century before Islam came to dominate Arabia, making it an important witness to the pre-Islamic Hijaz (the region where Mecca is located) and the religious background of the Quran's audience.

However, not everyone is fully convinced about the authors' identities.

The finding sheds light on the early days of Islam, the researchers said.

"Contrary to the popularly held belief that Islam was born in the full light of history, we don't know much about the rise of Islam from contemporary sources," Ahmad Al-Jallad, a professor of Arabic studies at The Ohio State University and the study's co-author, told Live Science. "That period of time is shrouded in mystery. These inscriptions provide a verifiable foundation for the writing of an evidence-based history of this period."

Yusef Bilin, a Turkish calligrapher visiting an ancient mosque in the city of Taif that's believed to have been built by Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, the fourth Caliph of Islam, noticed two inscriptions on a prominent boulder approximately 330 feet (100 meters) away. In 2021, he brought it to the attention of the study's authors. The inscriptions were written in Paleo-Arabic script, which describes the late pre-Islamic phase of the Arabic alphabet. The authors of the top and bottom inscriptions identified themselves as Ḥanẓalah, son of ʿAbd-ʿAmr-w and Abd al-ʿUzzē, son of Sufyān.

Related: '4,000-year-old wall found around oasis in Saudi Arabia likely defended against raids from nomads'

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The text translates to "In your name, our Lord, I am Ḥanẓalah [son of] ʿAbd-ʿAmr-w, I urge (you) to be pious towards God" and "In your name, our Lord, I am ʿAbd al-ʿUzzē son of Sufyān, I urge (you) to be pious towards God."

The authors studied the traditional Muslim biographies of Muhammad and genealogical records of Arabs and found that the combination of these names was exceedingly rare. One person with the name Ḥanẓalah, whose father was ʿAbd-ʿAmr, fit the bill. This person belonged to the Aws tribe — based in Yathrib (now known as Medina) — and features prominently as a companion of Muhammad in early Islamic literature.

The use of Paleo-Arabic easily puts these inscriptions in the late sixth or early seventh century and closely matches the timeline of Hanzalah, the companion, who died in the battle of Uhud in A.D. 625. The name of the second person, ʿAbd al-ʿUzzē, refers to the Arabian pagan goddess al-Uzza, further supporting the idea that the inscriptions were made by individuals who were not Muhammad's followers — or at least not yet.

These observations led the researchers to conclude that Ḥanẓalah is most likely the same one associated with Muhammad and that he etched these words while traveling through Taif, possibly with someone named ʿAbd al-ʿUzzē, before he accepted Islam.

"It's basically inconceivable that this inscription was made after Muhammad began his ministry, because the people in Taif were extremely hostile to him, and it's unlikely that one of his followers went there and left this inscription," study co-author Hythem Sidky, executive director of the International Quranic Studies Association in Washington, D.C., told Live Science.

Al-Jallad added that the patina of the inscription and the weathering patterns indicate that it had been there a long time, ruling out the possibility of a modern forgery.

"The article is a very impressive piece of scholarship," James Montgomery, a professor of Arabic and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "It is careful, meticulous and circumspect in its use of evidence, with every claim being properly substantiated by reference to all relevant and available evidence."

Although Montgomery thinks the identification is most likely accurate, he remained agnostic about the claim that the Ḥanẓalah mentioned in the inscription is the same one of Islamic tradition. "I would like to reserve judgment until we have two more inscriptions that also satisfy the stringent dating criteria the authors employ," he said.

Soumya Sagar holds a degree in medicine and used to do research in neurosurgery at the University of California, San Francisco. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science, Discover, and Mental Floss. He is a passionate science writer and a voracious consumer of knowledge, especially trivia. He enjoys writing about medicine, animals, archaeology, climate change, and history. Animals have a special place in his heart. He also loves quizzing, visiting historical sites, reading Victorian literature and watching noir movies.