People in Scandinavia may have used boats made of animal skins to hunt and trade 5,000 years ago

The people who created the Pitted Ware Culture may have used seal hides to build boats.

Ancient Scandinavians may have used boats constructed of animal skins to fish, hunt and trade, a new study suggests.

Known as the Pitted Ware Culture (PWC), this waterfaring Neolithic group of hunter-gatherers lived in Scandinavia between 3500 and 2300 B.C., according to the study, published Aug. 26 in the Journal of Maritime Archaeology.

The group is perhaps best known for its pottery, which features flat-bottomed vessels stylized with horizontal lines slashed into the clay before firing. They were also adept maritime hunters, particularly when it came to hunting seals.

Archaeologists think the PWC may have used the hides of these web-footed aquatic mammals to build watercraft, as well as oil from the seals' blubber to help maintain the boats.

"We know that these people were hunting lots of seals, as evidenced by the massive amounts of seal bones we're finding at sites that they inhabited," lead study author Mikael Fauvelle, a researcher in the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History at Lund University in Sweden, told Live Science. "Seals were also one of the best animals for making boats, as we know that the Inuit [an Indigenous group living in Canada, Greenland and Alaska] were applying oil from seals as a critical step in waterproofing their boats. We know that the PWC had large quantities of seal oil, which can be found in their pottery [at archaeological sites]."

Related: 2,700-year-old petroglyphs depicting people, ships and animals discovered in Sweden

Researchers analyzed the interiors of several pots and found traces of lipid residue from seal oil, Fauvelle added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Access to boats would have been vital to the PWC's survival; the culture was reliant on fishing due to living in an area bounded by several massive bodies of water, including the Baltic and North seas.

"They were moving across the environment and were trading quite often with other groups, often traveling from Gotland [an island in what's now Sweden] to Åland [an archipelago to the south] that is far away," Fauvelle said. "They would have been out in the ocean, traveling across big expanses of water."

Researchers think more primitive boats, such as canoes made from hollowed-out logs, would have been inefficient in traveling hundreds of miles across open water.

"These people had to paddle far and wide to hunt, fish and trade," Fauvelle said, adding that boats made of seal hide would have been sturdy enough for the job.

In fact, the boats — depending on their size — may have been large enough to transport up to about a dozen people at a time, as well as animals, including deer, bears and cattle, according to the study.

However, the researchers admit that they've found little physical evidence of the boats themselves, other than a few small fragments discovered over the years at sites across northern Sweden that "may represent direct evidence of Neolithic skin boat use," the authors wrote in the study.

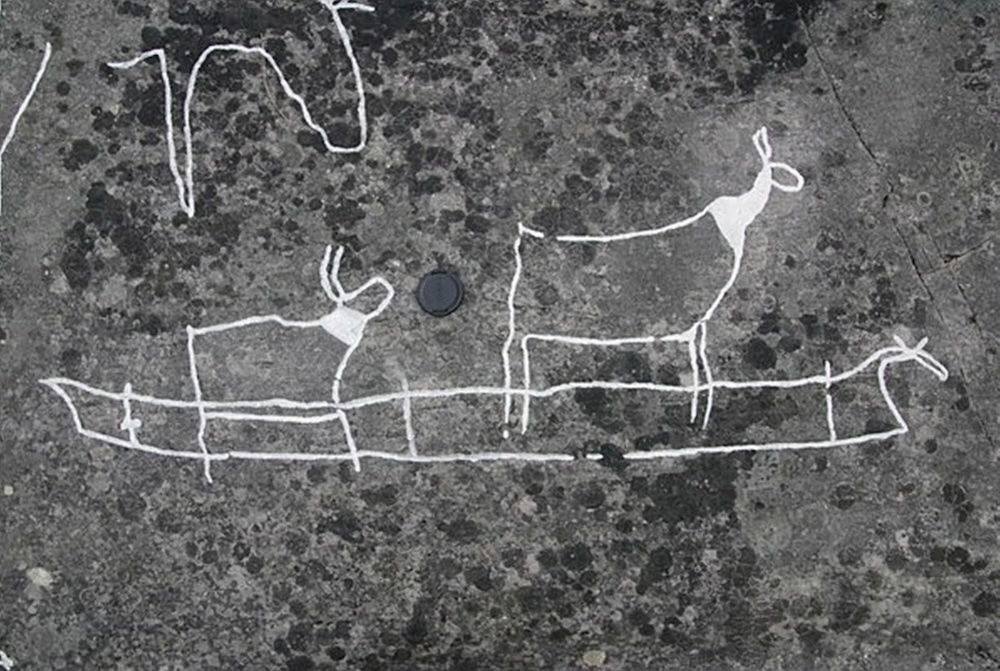

Perhaps the "strongest piece of evidence" is rock art depicting people traveling by boat. Some of the drawings include details of vessels equipped with harpoon rests that resemble animal heads, Fauvelle said.

"We've found drawings that are comparable to ethnographic skin boats made today and depictions of rectangular boats that are translucent and reveal the ribs or framework of the watercraft," he said.

The drawings, coupled with the possible fragments of boat frames, offer evidence that the PWC people were accomplished boat builders who understood "seafaring technologies" and would have used "advanced craft" to travel between different islands.

"If PWC people did use skin boats, the question remains as to why the technology may not have survived into the period of recorded history," the authors wrote.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.