Rare 'porcelain gallbladder' found in 100-year-old unmarked grave at Mississippi mental asylum cemetery

Archaeologists have discovered the burial of a woman with a rare "porcelain gallbladder" who was interred at the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum's cemetery 100 years ago.

About 100 years ago, a woman at Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum died with a condition so rare, it puzzled modern-day archaeologists who were excavating the asylum's unmarked graves.

But soon, thanks to help from their medical collaborators, the team determined the hard egg-shaped object in the skeletal remains of the woman's torso was a "porcelain gallbladder" — a condition never before found in an archaeological skeleton.

In a study published March 30 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, researchers detailed the rare discovery of a gallbladder that had been preserved for a century. While organs normally decay completely over time after a person's death, in this case, the gallbladder had calcified, a process in which calcium builds up in the muscular wall of the organ, causing it to harden.

The preserved organ, often called a porcelain gallbladder in the medical literature, was associated with the skeleton of a middle-aged woman who was buried in the asylum's cemetery. Founded in 1855 and closed in 1935, the asylum treated tens of thousands of patients, around 7,000 of whom died while in residence and were buried in simple pine boxes with wooden markers.

The cemetery was rediscovered in 2012 during development of the land, which is now on the grounds of the University of Mississippi Medical Center. Exhumations by the Asylum Hill Project began in 2022, led by UMMC bioarchaeologist Jennifer Mack.

Related: Centuries-old skeleton with massive, crippling bone growth unearthed in Portugal

"Gallbladder disease is fairly common in modern American populations, though rates have increased in the last few decades," Mack told Live Science in an email. But although tiny gallstones have occasionally been found in archaeological contexts, this is the first reported discovery of a porcelain gallbladder in a cemetery burial.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In modern medical studies, porcelain gallbladder is considered a rare condition resulting from chronic inflammation of the organ, a disease called cholecystitis. The exact reason that porcelain gallbladder forms is unknown, but it is clear that the wall of the organ mineralizes. People with this condition are usually asymptomatic, and it affects women five times more than men.

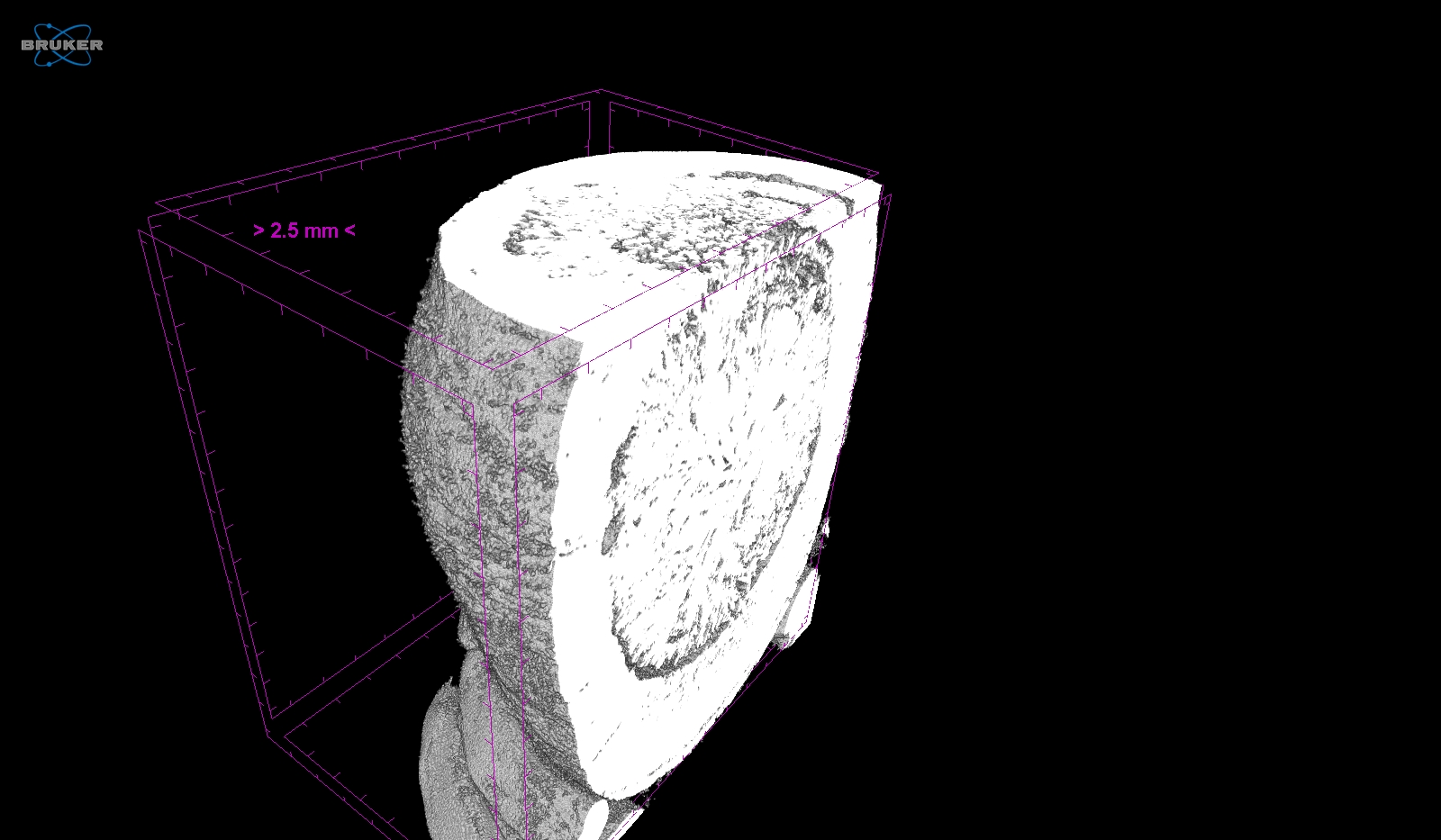

Measuring 1.8 inches (46 millimeters) long and 1.1 inches (28.5 mm) wide, the object in the burial weighed just over half an ounce (16.1 grams). It was identified as a porcelain gallbladder through X-rays and micro-CT scans carried out at UMMC because, underneath the irregular surface of the calcified rim, the research team found a single large gallstone.

"It's funny that the object was initially an exciting mystery for the bioarchaeologists," Mack said, "whereas it was identified almost at a glance by the retired surgeon on our project."

Within the first 100 burials recovered by the Asylum Hill Project, the researchers noted in their study, they found five people with gallstones in addition to the woman with porcelain gallbladder. "The apparent high proportion of asylum patients with cholecystitis is coincidental," they wrote, "as there is no association between gallbladder disease and mental illness or physiological diseases causing neuropsychiatric symptoms."

Francesco Maria Galassi, a paleopathologist at the University of Lodz in Poland who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that he finds this collaborative research interesting and agrees with the diagnosis. However, Galassi wonders whether medication used in the past could have put these asylum patients at greater risk of gallbladder disease.

"For example," Galassi said, "opium use is known to contribute to the spasm of the sphincter of Oddi," a muscle that opens and closes so bile and pancreatic juice can flow into the small intestine, resulting in the slowing or stoppage of bile in the tube connecting the liver and gallbladder. Galassi suggested that, if possible, "it would make sense to investigate the drugs administered to the patients of this lunatic asylum and evaluate potential health correlations."

While the asylum closed prior to the beginning of the antibiotic era, Mack said, "It's too early in the process of historical records research to really say anything about what pharmaceutical treatments were being regularly provided for physiological or mental illnesses."

Additional testing of the contents of the porcelain gallbladder may happen in the future, the researchers wrote in the study. The goal would be to create a chemical composition database that will help archaeologists better identify gallstones, Mack said.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.