Remains of hundreds of 7,000-year-old 'standing stone circles' discovered in Saudi Arabia

Archaeologists in Saudi Arabia have now excavated eight ancient stone circles that likely served as homes to people more than 7,000 years ago.

Archaeologists in Saudi Arabia have excavated eight ancient "standing stone circles" that they say were used as homes.

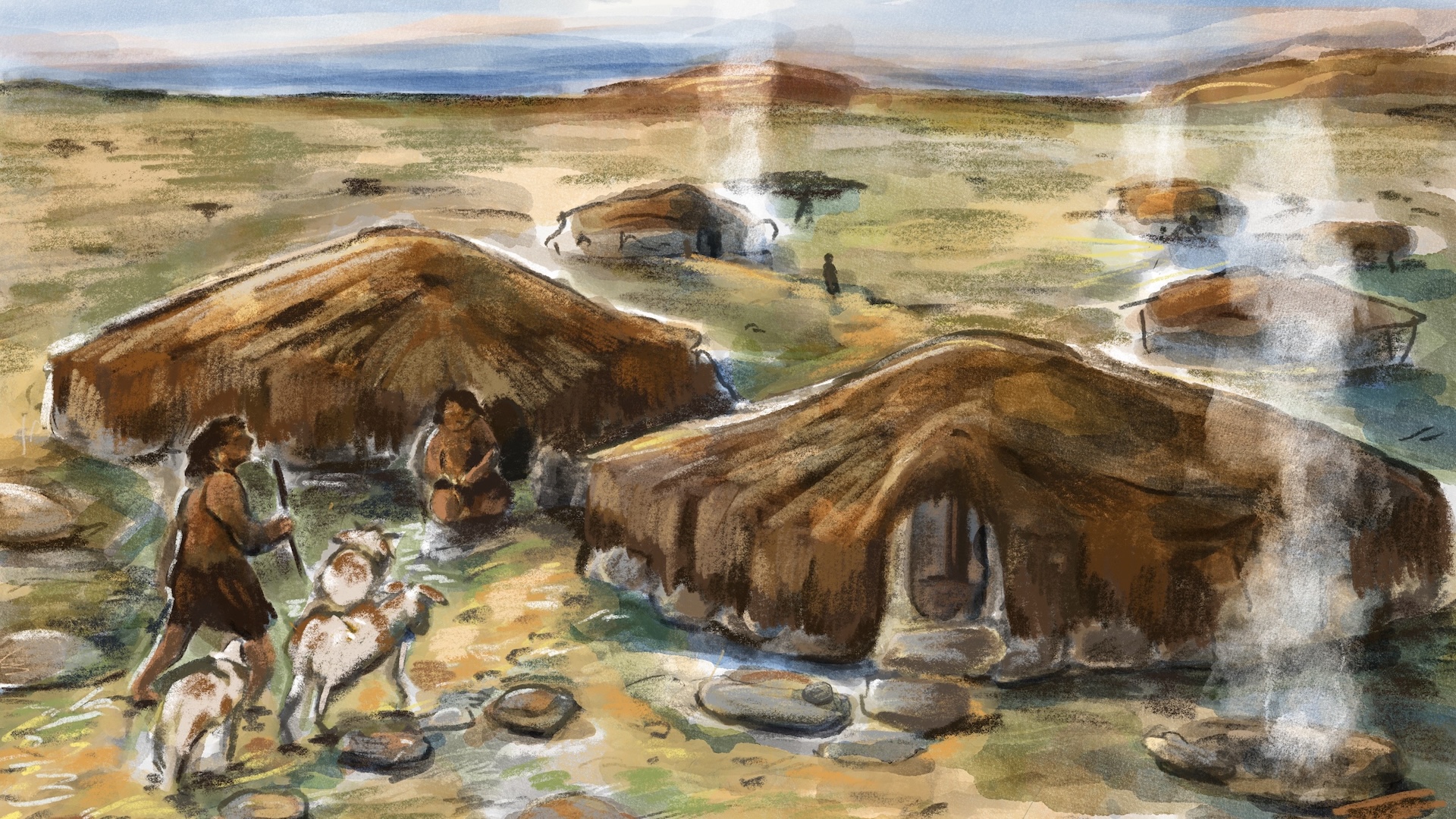

About 345 of these structures were identified through aerial surveys across the Harrat 'Uwayrid, a lava field near the city of AlUla in northwestern Saudi Arabia, the team reported July 2 in the journal Levant. The circles range from 13 to 26 feet (4 to 8 meters) in diameter and have at least one standing stone at the center.

The circles date back around 7,000 years and have the remains of stone walls and at least one doorway. They would have had roofs made of either stone or organic materials, the team wrote.

During their excavations, the archaeologists discovered the remains of many stone tools made of basalt. Five of the standing circles alone yielded nearly 500 pounds (225 kilograms) of stone tools or debris, the team wrote. The archaeologists also found the remains of bones from sheep, goats and cows.

Also among the finds were a variety of seashells, all of which came from the Red Sea, which is located about 75 miles (120 kilometers) to the west. The presence of the seashells "suggests developing networks of trade and exchange, concurrent with mobility," the team wrote.

Related: Vast 4,500-year-old network of 'funerary avenues' discovered in Saudi Arabia

The artifacts found in the circles, combined with the circles' similarity to ancient homes excavated in Jordan, suggest that many, if not all, of the standing stone circles are also domestic structures, the team noted.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While modern-day people may sometimes associate stone circles like those at Stonehenge with a ritual purpose, it's important to note that many early domestic structures were circular.

"Globally, early domestic architecture was always round, and rectangular houses only appear in the later Neolithic," Jane McMahon, an honorary research fellow at the University of Western Australia and lead author of the paper, told Live Science in an email.

Different landscape

Around 7,000 years ago, the environment in northern Saudi Arabia was much wetter than it is today, but farming had not yet come into use. "There's no evidence of farming domesticated species of plants like wheat and barley, but gathering wild plants likely took place, and perhaps manipulating the landscape to increase the likelihood and yield of wild species," McMahon said.

When these standing stone circles were in use, another form of stone structure, known today as a mustatil (Arabic for "rectangle"), was being built as well. Excavations at the mustatils suggest they had a ritual purpose that may have included the sacrifice of cattle. The contemporaneous use of the mustatils and standing stone circles indicates that it is "likely that these two megalithic structure types are aspects of a single cultural entity," the team wrote.

Gary Rollefson, a professor emeritus of anthropology at Whitman College and San Diego State University who was not involved in the research but has conducted extensive archaeological work in the region, said he thinks the people who built the standing stone circles and mustatils are descended from people who lived in Jordan and Syria about 500 years earlier.

He told Live Science that the architecture of the standing stone circles is similar to that of structures found in Jordan dating to about 500 years earlier, and the people who built the structures in Jordan also herded sheep, goats and cattle. The migration may have been spurred by an increase in population brought about by new hunting technologies, such as the "kite," a series of stone walls used to force wild animals into a kill zone. These hunting advances dramatically increased the supply of food, which, in turn, led to an increase in the human population in the Jordan/Syria area.

"They were building up a large population in eastern Jordan and [parts of] Syria," Rollefson said, and they needed to find new hunting grounds, which would have led them to gradually go south, into what is now Saudi Arabia.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.