'Ritual text' from lost Indo-European language discovered on ancient clay tablet in Turkey

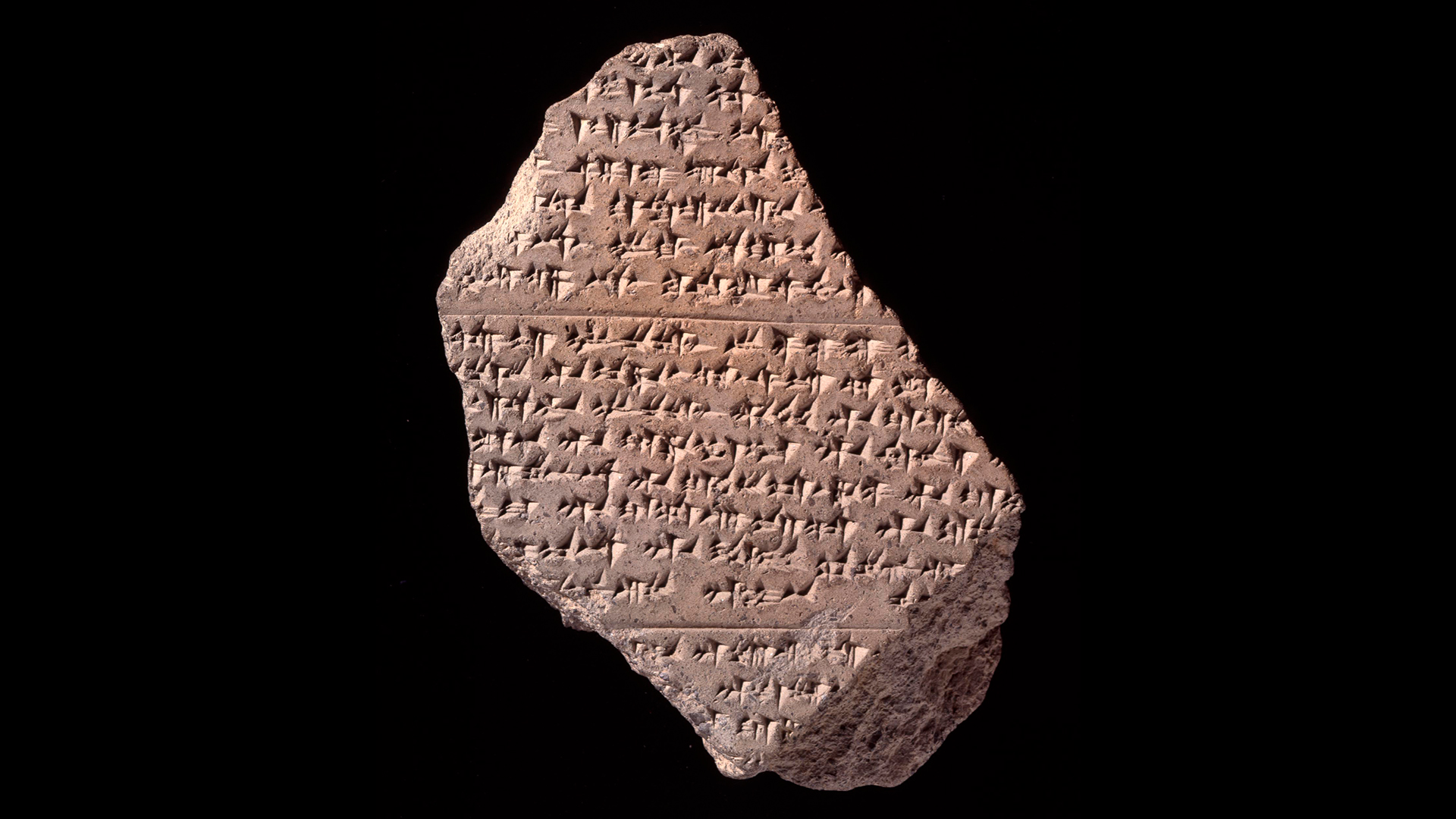

Researchers are still studying the ancient text of an unknown language, written in cuneiform on a clay tablet.

Words from a "lost" language spoken more than 3,000 years ago have been discovered on an ancient clay tablet unearthed in Turkey.

Archaeologists discovered the tablet earlier this year during excavations at Boğazköy-Hattuşa in north-central Turkey, the site of Hattusha, the Hittite capital from about 1600 B.C. until about 1200 B.C. and now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Annual expeditions to the site led by Andreas Schachner, an archaeologist at the German Archaeological Institute, have unearthed thousands of clay tablets written in cuneiform — perhaps the most ancient written script, created by the Sumerians in Mesopotamia more than 5,000 years ago.

The tablets are "mainly found in clusters connected to half a dozen buildings," sometimes described as archives or libraries, Schachner told Live Science. "But we find text all over the [site] that are moved around by erosion."

Most of the tablets unearthed at Boğazköy-Hattuşa are written in the language of the Hittites, but a few include words from other languages — apparently because the Hittites were interested in foreign religious rituals.

Related: What's the world's oldest civilization?

The words in the previously unknown language appear to be from such a ritual, which was recorded on a single clay tablet along with writing in Hittite explaining what it was.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The introduction is in Hittite," Schachner said in an email. "It is clear that it is a ritual text."

Lost language

The clay tablet was one of several sent to Germany to be analyzed, where it was studied by Daniel Schwemer, a professor and chair of Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the University of Würzburg. From the Hittite introduction, he identified it as the language of Kalašma, a region on the north-western edge of the Hittite heartland near the modern Turkish city of Bolu.

The scholars don't know what it says yet, and they're not releasing any photographs of the tablet until it has been fully studied.

But they've determined that it belongs to the Anatolian group of the Indo-European family of languages, which the Hittite language also belonged to; other ancient languages in the region, including Akkadian, Hebrew and Aramaic, belong to the Semitic family of languages.

Schwemer said in a statement that "the Hittites were uniquely interested in recording rituals in foreign languages." Extracts of rituals in other foreign languages have also been found in the tablets from Boğazköy-Hattuşa, including in the Indo-European languages Luwian and Palaic and a non-Indo-European language known as Hattic.

Such ritual texts were written by Hittite scribes and reflected various Anatolian, Syrian and Mesopotamian traditions and linguistic milieus.

"The rituals provide valuable glimpses into the little-known linguistic landscapes of Late Bronze Age Anatolia, where not just Hittite was spoken," Schwemer said.

Hittite Empire

For centuries, the Hittites, who ruled over most of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and Syria, were among the most powerful empires in the ancient world. In 1274 B.C., the Hittites fought the Battle of Kadesh against the Egyptians for control of Canaan — what's now southern Syria, Lebanon and Israel.

The battle may be the earliest military action ever recorded. It seems to have been a defeat for the Hittites; although they kept control of the city of Kadesh, the Egyptians kept control of Canaan.

Hattusha became the Hittite capital in about 1600 B.C.; and more than 100 years of archaeological excavations at the site have revealed a vast ancient city there.

But it was abandoned in about 1200 B.C. during the cataclysmic "Late Bronze Age collapse" that suddenly ended or damaged many ancient states in the eastern Mediterranean; the collapse has been ascribed to invasions by migrants called the "Sea Peoples", sudden climate changes, and disruptive new technologies like iron — but historians and archaeologists debate the causes.

Schachner said it wasn't possible to foresee if any other writings in the "lost" language would be found, or if extracts from still other ancient languages would be found in the tablets from Boğazköy-Hattuşa.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.