Ancient Roman camps from secret military mission spotted using Google Earth

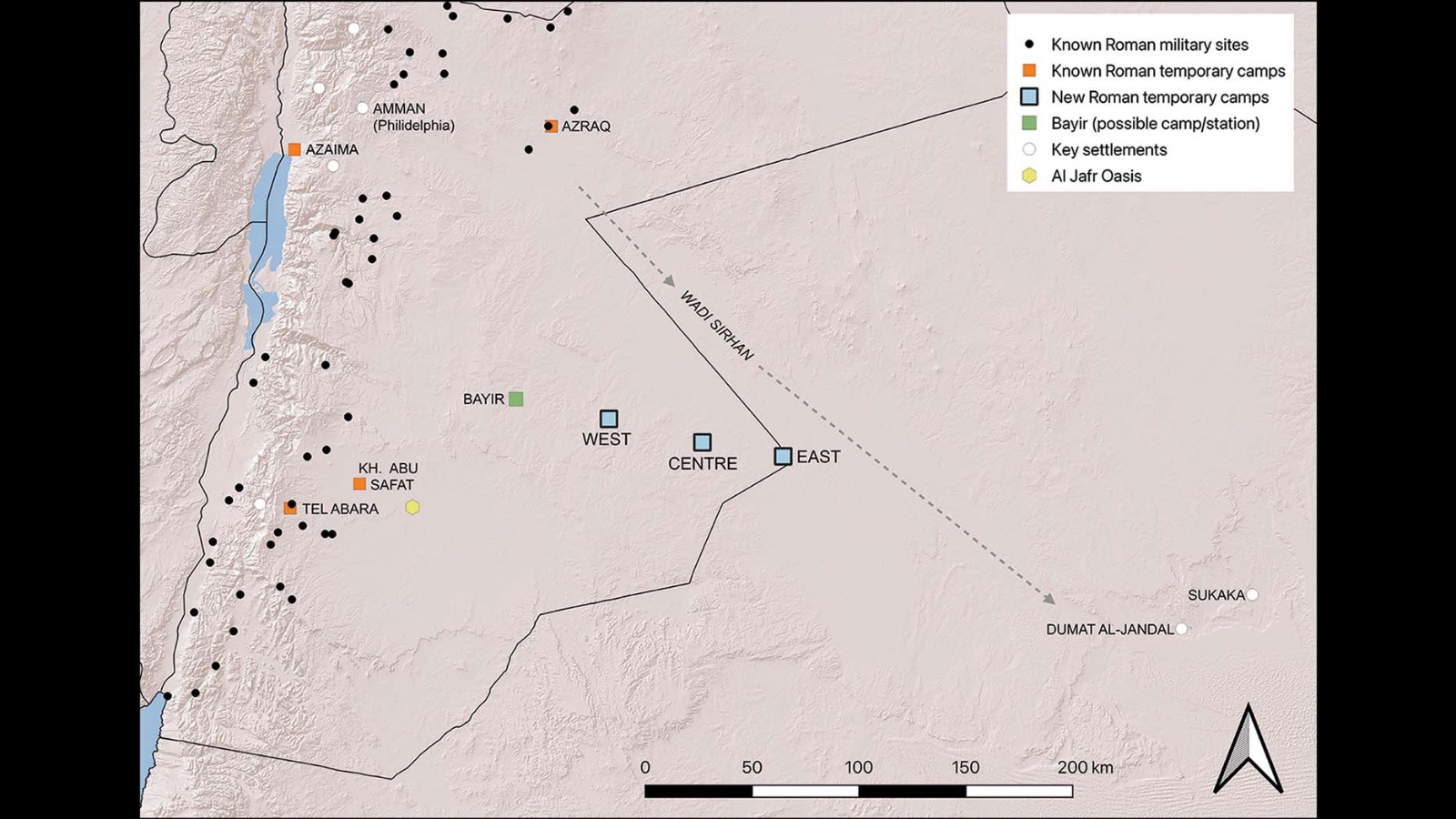

An archaeologist using Google Earth has spotted the traces of three Roman military camps in the southern Jordanian desert, prompting a rethink of the region's history.

Three ancient Roman camps in the Jordanian desert, possibly built during a secret military mission in the second century A.D., have been discovered by an archaeologist using satellite images from Google Earth.

Only a handful of Roman camps have been found in the Middle East — unlike in Roman territories in Europe, where hundreds are known — and experts say the discovery is an important archaeological advance.

Just the outlines of the camps are visible via Google Earth; no buildings or high walls remain. The camps are so far out in the desert that no scientist has visited them on foot, although tire tracks show several vehicles have been in the area, according to a study published April 27 in the journal Antiquity.

Study lead author Michael Fradley, a landscape archaeologist at the University of Oxford, told Live Science that a wall of one camp had at some point been recorded on a Jordanian heritage register. "But there'd been no interpretation of it as a Roman camp," he said.

Related: 25 strangest sights on Google Earth

Eye in the sky

Fradley works with a project called Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa (EAMENA) to analyze satellite photographs, and Google Earth is among its sources.

"There are problems with some areas that don't have good imagery, but it's still the go-to tool for lots of geographical researchers" mainly because the open-source imagery it uses is free to access, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fradley was using Google Earth last year to examine photographs of the desert near Jordan's southern border with Saudi Arabia when he spotted the classic "playing card" shape of a Roman camp. Less than 24 hours later, he'd spotted two more, leading in a line from an oasis at Bayir roughly southeast into the desert.

Further investigations with Google Earth and from aerial photographs suggest that the outlines are the distinctive remains of temporary Roman military camps, built by soldiers following a standard defensive plan — in these cases, by piling up rocks.

The camps are farther apart than a person could easily walk in a day — about 23 to 27 miles (37 to 44 kilometers) — and Fradley estimates they were occupied by hundreds of mounted troops, maybe on camels.

Secret mission

There's no record of a Roman incursion into this region, and in the second century, it was controlled by the kingdom of the Nabataeans, a Bedouin people and ostensibly Roman allies who followed the empire's directives.

The line of camps seems to be heading for the Nabataean city of Dumat al-Jandal, which is now in Saudi Arabia. But the usual approach to the city would have been through a dry valley farther north called Wadi Sirhan; Fradley speculated that the camps were part of a secret Roman mission to attack from an unexpected quarter.

Roman records indicate that after its king died in A.D. 106, the Nabataean kingdom passed peacefully into direct Roman rule, during the reign of Emperor Trajan. But the new discoveries suggest the transition to Roman rule may have been more violent than previously thought, Fradley said.

It's not known what happened to the soldiers who made this journey into the desert. They may have turned back before reaching Dumat al-Jandal, or they may have continued on to other camps farther east, of which no signs remain, he said.

David Kennedy, a professor emeritus of classics and ancient history at the University of Western Australia who wasn't involved in the study, noted that only a few Roman military camps have been found in the Middle East, and so the discovery is important evidence for the study of the Roman army in Arabia.

Dating such camps could be difficult, but their outlines seemed to point to the first two centuries A.D., he said.

Beyond that, archaeologists would have to travel to the sites and search for any artifacts they could use to date them, although that's unlikely: "[It's] not a hopeful undertaking, but necessary," he said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.