'It was not a peaceful crossing': Hannibal's troops linked to devastating fire 2,200 years ago in Spain

Researchers think a farmhouse in the Pyrenees was set on fire by Carthaginian troops on their way to attack Rome.

The advance of the Carthaginian general Hannibal on Rome during the Second Punic War caused havoc to those in his path, and a devastating fire in an Iron Age farmhouse may be evidence of the damage wrought by his troops more than 2,200 years ago, a new study finds.

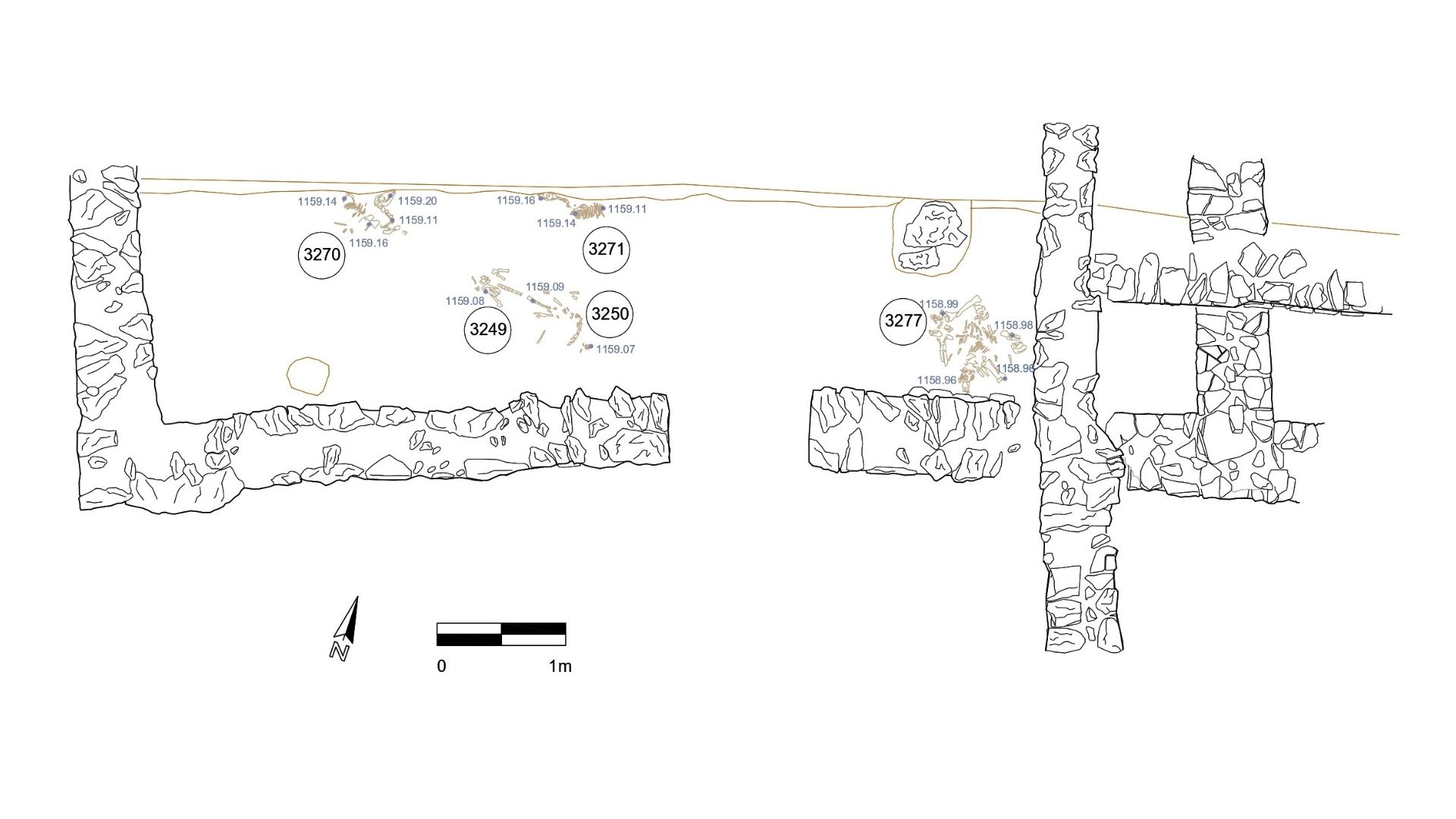

The fire completely destroyed the farmhouse and almost everything in it — including four sheep, a goat and a horse — but the people who lived there seem to have escaped, as no human remains were found, said study lead author Oriol Olesti Vila, an professor of Antiquity and the Middle Ages at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

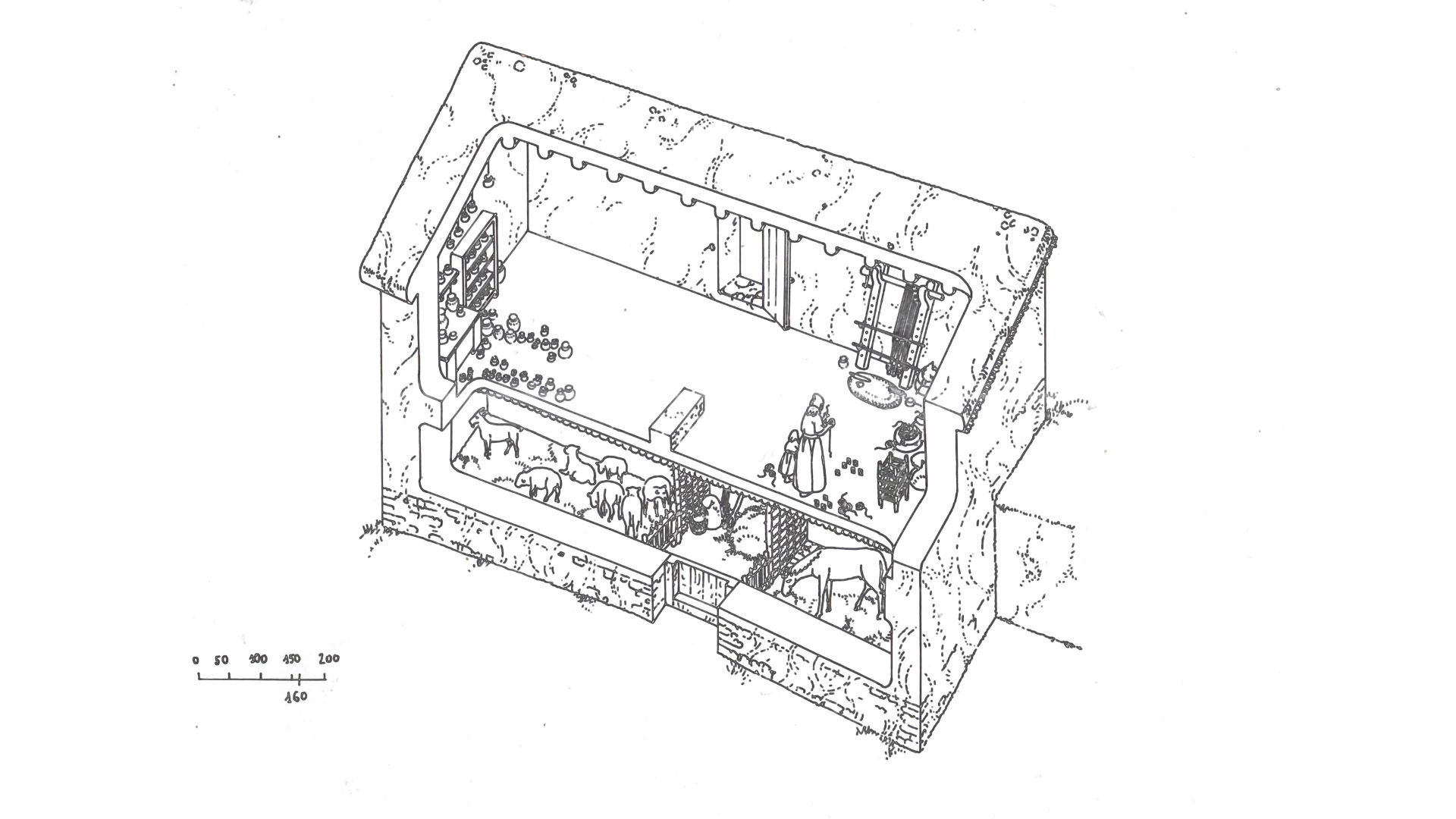

"This was a very large fire," he told Live Science. "The roof and the ceiling were of wood, and two floors were separated by a wooden partition. … The whole building was destroyed."The study, published Friday (May 17) in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, describes the archaeological excavations and analyses of the remains of Tossal de Baltarga, an Iron Age settlement in the Pyrenees mountain chain about 70 miles (115 kilometers) north of Barcelona in Spain's Catalonia region and near the border with France.

The artifacts there include a single gold earring, which seems to have been deliberately concealed and may be evidence of the Carthaginian attack, Olesti Vila said.

Related: How (and where) did Hannibal cross the Alps? Experts finally have answers

Mountain village

The settlement at Tossal de Baltarga was home to a group of the Ceretani, a pre-Roman people who were famous for raising cattle in the mountain valleys and were mentioned in both Greek and Roman writings around that time, Olesti Vila said.

Much of the settlement was badly damaged during its millennia underground, but the remains of the farmhouse survived because the Romans who later settled in the area built a structure on top of it, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Coins from southern Gaul (modern-day France) discovered at the site date the destructive fire to the last quarter of the third century B.C. — the time of the Second Punic War between Carthage and Rome, from 218 to 201 B.C.

Olesti Vila thinks the entire settlement was set ablaze by the marauding troops of the Carthaginian statesman and general Hannibal Barca, who famously took his armies from Carthage in North Africa and across what are now Spain, southern France and the European Alps to invade Italy.

Hannibal's greatest exploit was bringing war elephants across the Alps to aid his invasion — probably the first elephants ever seen in Europe — and at one point, he controlled most of southern Italy.

Punic wars

But Rome regrouped, and in 204 B.C., the Roman general Publius Scipio invaded Carthaginian Africa; Carthage then recalled Hannibal and his armies from Italy but ultimately suffered defeat. Scipio was thereafter known as Scipio Africanus — "the African" — and Carthage became subordinate to Rome; but it was destroyed in 146 B.C. at the end of the Third Punic War, which Rome instigated for political reasons.

Olesti Vila said the Greek historian Polybius (who lived circa 200 to 118 B.C.) recorded that Hannibal fought several battles during his crossing of the Pyrenees, and it was likely that the destructive fire at Tossal de Baltarga was a consequence of these.

"It was not a peaceful crossing," he said.

Although household fires were common in the Iron Age, they usually affected only a single room. But in this case, the fire destroyed the entire house and there is evidence of such a fire in many of the settlement's other buildings, Olesti Vila said.

In addition, the fact that the animals were penned in the lower floor of the house instead of roaming in outdoor pastures was evidence that the people of the settlement were expecting some sort of attack. Plus, the burned remains of a dog, which had probably been tied up, were found in the remains of another building.

The single gold earring, too, seems to have been deliberately hidden inside a little pot on the second floor of the house, which could be further evidence that the householders suspected trouble, Olesti Vila said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.