'Magical' Roman wind chime with phallus, believed to ward off evil eye, unearthed in Serbia

Phallic objects like this were common in the Roman world to ward off evil.

Archaeologists have unearthed a Roman wind chime called a tintinnabulum — featuring a prominent phallus — at an archaeological site in eastern Serbia.

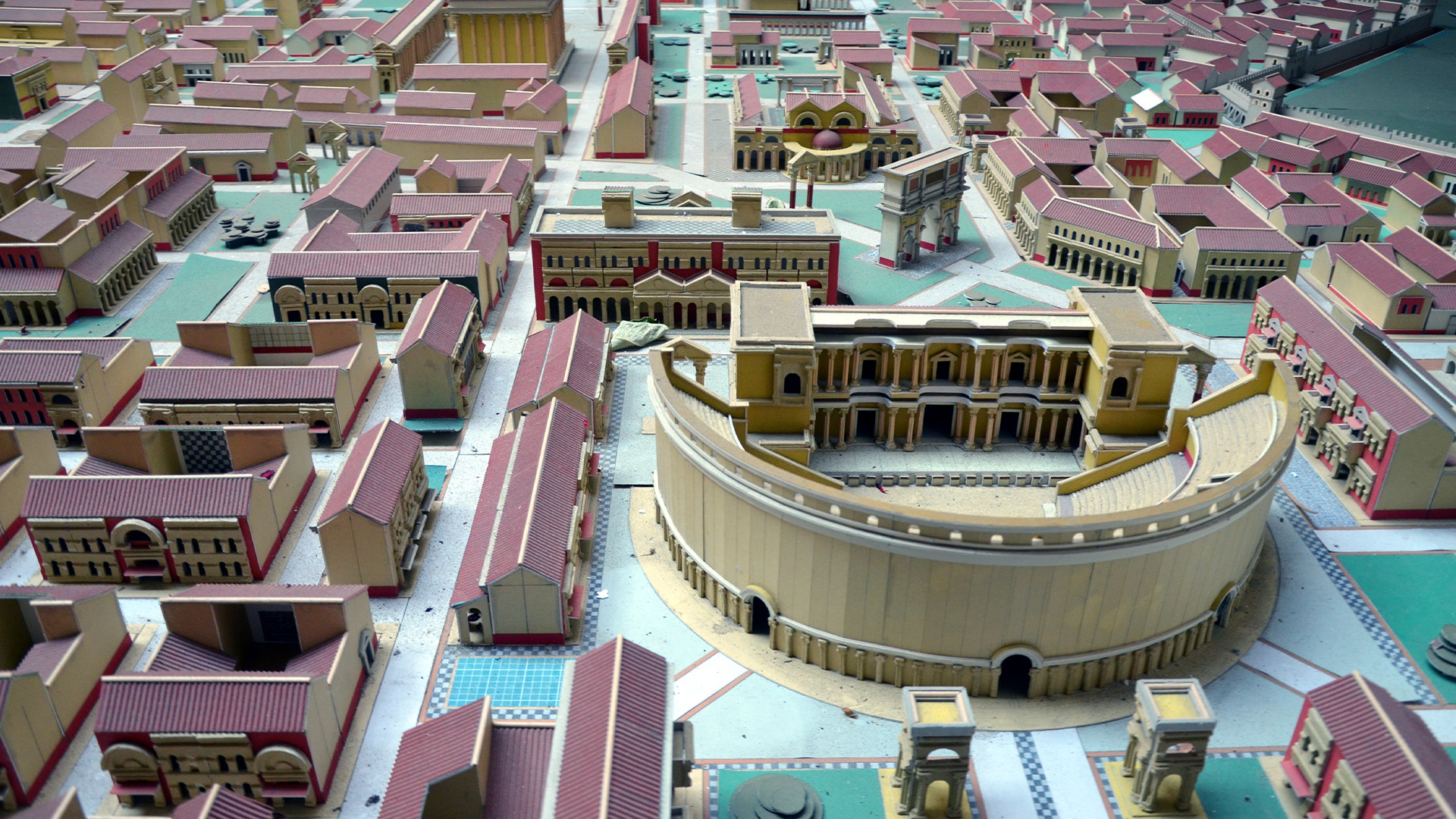

Such objects, which were hung near the doorways of houses and shops, were believed to serve as magical protection for the premises. This one was discovered on the porch of a large home on a main street in Viminacium, an ancient Roman city, the extensive ruins of which now lie near the Serbian town of Kostolac, about 30 miles (50 kilometers) east of Belgrade.

"The building was destroyed in a fire, during which the porch collapsed and fell to the ground," Ilija Danković, an archaeologist at the Institute of Archaeology in Belgrade, told the Serbian-language website Sve o arheologiji.

Tintinnabulums were designed to catch the wind, supposedly so their noise and unusual appearance would frighten off evil spirits and ward off the curse of the evil eye, which was greatly feared in antiquity.

Viminacium was the civil and military capital of Rome's Upper Moesia province from the first to fifth centuries, until it was sacked by the Huns under Attila in 441. The city was rebuilt under the Byzantine emperor Justinian, but it was finally destroyed by invading Slavs in about 535.

Magical phallus

This is the second tintinnabulum found in the ruins, Danković told Live Science. The first is now in a private collection in Austria; nothing is known about its discovery, he said.

However, the newly discovered tintinnabulum was discovered in its full archaeological context. "As soon as we started uncovering it, we knew immediately what we had discovered," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The latest tintinnabulum from Viminacium is made of bronze, but it is being kept surrounded by soil until it can be properly restored. As a result, its exact configuration isn't known. But it is centered on a "fascinum" — a portrayal of a magical phallus — with two legs, wings and a tail, he said.

"Judging by what can be seen … it had four bells and the chain from which it hung," Danković said, adding that there also seemed to be other elements to the design not seen on other tintinnabulums.

Roman beliefs

The symbol of a phallus wasn't always erotic or obscene for the ancient Romans, Danković said. "It was a bringer of good fortune and happiness, and an efficient weapon to combat the evil eye," he said. "For this reason, phalluses can be seen everywhere in the Roman world, from wine cups to the amulets worn by children."

He added that the symbol was often publicly displayed to summon prosperity and deter thieves.

The discovery of the tintinnabulum is evidence that Viminacium was "in every sense a part of the Roman world," Danković said.

Not only did its people share many Roman beliefs, he said, but it's likely that the tintinnabulum was imported from elsewhere in the empire, showing that there were social elites at Viminacium who were willing to pay a significant amount of money for such an object.

Ken Dark, an archaeologist and historian at King's College London who wasn't involved in the discovery, said the Viminacium tintinnabulum was a type of "apotropaic" amulet that was designed to ward off evil influences and give protection to people or their property.

Such amulets "were common in the Roman world, and these sometimes took forms which would seem very strange — or even comical — to us today," he told Live Science in an email.

Editor's Note: This article was corrected at 9:00 a.m. E.S.T. on Nov. 14 to note that Ilija Danković was the interview source for quotes about the Viminacium, rather than a spokesperson for the archaeological site.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.