Royal tomb in Benin has traces of human blood on its walls, hinting at human sacrifice, study finds

Researchers examining the wall of a ceremonial tomb in Benin found proteins that could have come only from human blood.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Nearly 200 years ago, human blood is said to have been incorporated into a ceremonial tomb built within a royal palace complex in what is now Benin, according to legend. Now, an investigation into the proteins found within the tomb's walls reveals evidence that the legend is true.

According to a new study, the tomb at Abomey, once the capital of the West African kingdom of Dahomey, contains proteins that could have come only from human blood, confirming the site's grisly history.

It's one of the first times such a discovery has been made through "paleoproteomics," the study of trace proteins left behind in archaeological contexts.

Article continues below"This discovery is important, as it provides concrete evidence of historical rituals and practices," biochemist Jean Armengaud, an expert on ancient proteins at France's Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission, told Live Science.

Armengaud is the senior author of the new study, which was published May 29 in the journal Proteomics. He and his colleagues examined samples taken at the tomb between 2018 and 2022, during excavations at the site by archaeologists from France and Benin.

Related: 7 extraordinary African kingdoms from ancient times to centuries ago

According to local lore, the tomb within the Abomey palace complex — built in the 19th century by King Ghezo of Dahomey, in honor of his brother King Adandozan — used plaster that included the blood of 41 human sacrifices; 41 was considered a sacred number, the authors wrote in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dahomey king

Ghezo, who ruled from 1818 until 1858, famously led several military expeditions against the region's powerful Yoruba state, or Oyo Empire, and thereby ended the Dahomey kingdom's annual tribute of slaves.

He was considered a powerful ruler and reportedly showcased the deaths of his foes to secure his reign. According to historical accounts, the path to his hut was paved with the skulls and jawbones of defeated enemies, and one of his thrones stood on the skulls of four enemy leaders.

Dahomey, now called Benin after the nearby Bight (or Bay) of Benin, is a center of the original African Vodun or Vodou religion that was developed in the Caribbean region. Traditional Vodun often features sacrifices of animal blood.

Distinctive proteins

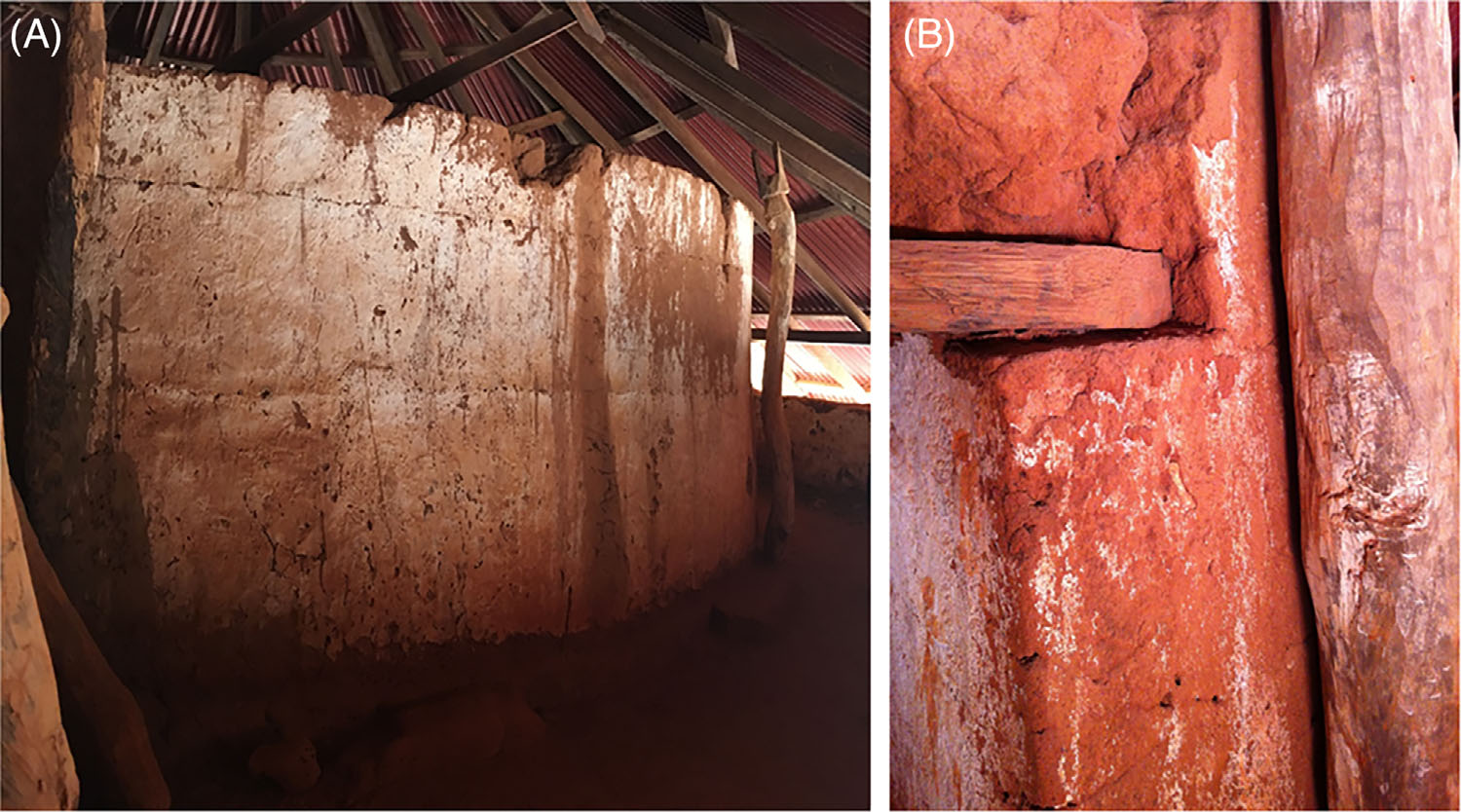

The researchers applied a technique called tandem mass spectrometry —to proteins contained in samples of the wall of the tomb, which consists of two round huts joined together. The method breaks down ions into fragments to reveal their chemical structure.

Their study yielded more than 10,000 matches in a database of proteins that identified the presence of thousands of microorganisms, as well as both human and chicken blood.

"Since proteins are more stable molecules compared to DNA, paleoproteomics can provide extensive information about the organisms that produced these proteins in ancient times," Armengaud said.

The results show clearly that human blood was one of the substances in the wall — in line with historical accounts, never verified until now, that claimed blood from human sacrifices was mixed with "red oil" and sacred water to make the plaster.

In this case, Armengaud said, the paleoproteomic study was preferable to a paleogenomic study with ancient DNA, which might detect genetic material from individuals, such as the people who built the structure, without determining how they were involved.

But paleoproteomics and paleogenomics can also complement each other. Armengaud hopes DNA sequencing of samples from the Abomey tomb can identify the number of sacrificial victims and their origins, thereby providing a more detailed historical context.

Matthew Collins, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge who wasn't involved in the latest study, told Live Science that the research showed how proteomics could be applied in complex and challenging situations.

"If you were using DNA, then you could tell that certain species were present — but what you couldn't determine is the type of tissues that were involved," he said. "But here you've got evidence of tissue proteins associated with human blood."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus