Satellites spy remnants of hidden Bronze Age settlement in Serbia

The more than 3,000-year-old site along a riverbank in Serbia contains the footprints of dozens of Bronze Age structures.

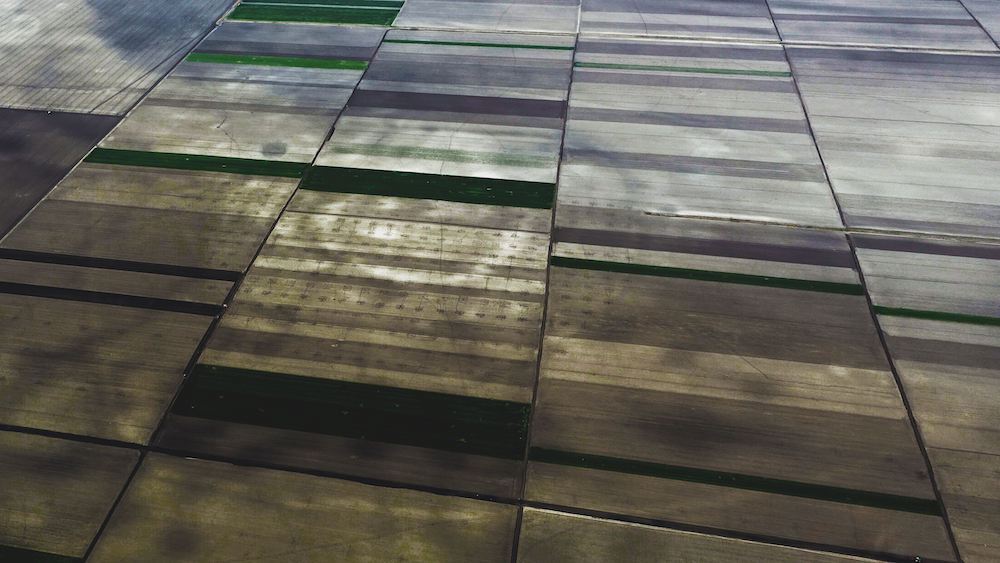

Satellite imagery has revealed a network of more than 100 Bronze Age structures hidden in the Serbian plains.

Archaeologists first noticed the remnants of the more than 3,000-year-old enclosures in 2015 while reviewing Google Earth photos of a 93-mile stretch (150 kilometer) of wilderness along Serbia's Tisza River, according to a study published Nov. 10 in the journal PLOS One.

"We could see traces of over 100 Late Bronze Age settlements," study lead author Barry Molloy, an associate professor of archaeology at University College Dublin, told Live Science in an email. "What is fascinating about the [sites] is that we not only identified their presence in these images, but also measured their size and, for many, how people organized the layout inside their settlements."

He added, "It is quite unique in European Bronze Age archaeology to get this level of detail for so many settlements in such a specific area."

Previously, this area, known as the Pannonian Plain, was thought to be a hinterland not used for Bronze Age settlements. But now, researchers think that this is just one example of the many settlements found across Europe that are part of an extensive trade network from the time.

Related: 'Magical' Roman wind chime with phallus, believed to ward off evil eye, unearthed in Serbia

In addition to analyzing satellite images, for the new study, researchers visited the site via small plane and in person and found the footprints of dozens of structures "hiding in plain sight," according to Science magazine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most of the enclosures were built close together, similar to neighborhoods today, suggesting that the inhabitants "chose to live together very closely" in what Molloy described as a "complex and well-organized society."

"The pale soil patches do not follow any specific alignments, but they are evenly spread out, lying a few tens of meters apart from each other," Molloy said. "While we need to excavate to confirm details, our suspicion is that these were places where extended families lived."

Due to farmers plowing the land for many years, the outlines of many of the enclosures were practically invisible from the ground. However, archaeologists did find what was left of several walls and ditches, which may have been used as ramparts to help protect the settlement, according to the study.

"Unfortunately, these only remain visible in aerial images because they have been filled in and plowed down over centuries of agriculture, including intensive plowing during the 20th century," Molloy said. "A wooden palisade or wall may have run around the top of the ramparts, as we see at other sites in the region."

There are a few clues as to why the settlement would've been so heavily fortified. Based on the discovery of clay chariots and weaponry at cemeteries near some of the enclosures, it's likely that the inhabitants were "familiar with warfare" — not amongst each other, but rather, with the outside world, according to Science.

Researchers also unearthed "large quantities" of artifacts including grinding stones used for processing grain, pottery shards and pieces of bronze, including a pin used for fastening clothing. Radiocarbon dating of animal bones strewn about the site confirmed its ancient occupation, Molloy said.

"[It] would have been occupied from 1600 to 1200 B.C.," Molloy said. "On occasion, we found pieces of burnt daub indicating structures there had been damaged by fire. Daub was soil applied to walls of thin sticks — wattle — to make structures like houses in the past."

However, archaeologists aren't sure what caused the settlement to be abandoned around 1200 B.C.

"This remains a bit of a mystery for now," he said. "It is possible that they simply became more mobile and moved around the landscape in a less constrained manner."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.