Scientists discover what could be the oldest evidence of cannibalism among ancient human relatives

Nine cut marks on a 1.45 million-year-old hominin bone suggest another hominin, possibly of the same species, slashed the bone to strip the flesh and eat it.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 1.45 million years ago, ancient human relatives ate one of their own, chowing down on meat from a shinbone, according to cut marks that constitute the oldest decisive evidence that our relatives butchered and made a meal out of one another, a new study finds.

However, it's unclear whether the cut marks are indicative of cannibalism, as multiple human relatives existed at this time, meaning that one hominin species — a group that includes modern and extinct humans, as well as our closely-related ancestors — could have eaten a related hominin species.

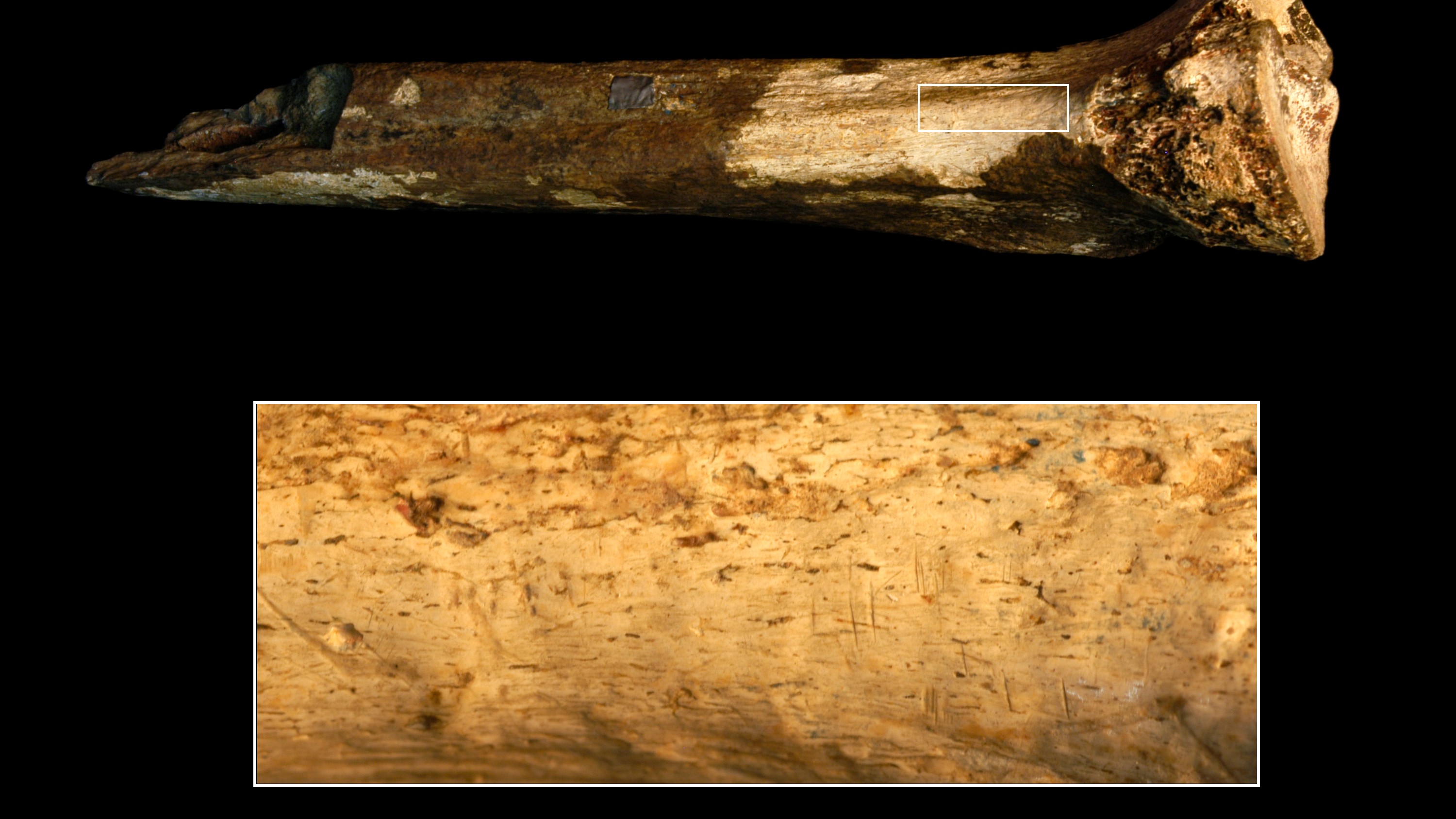

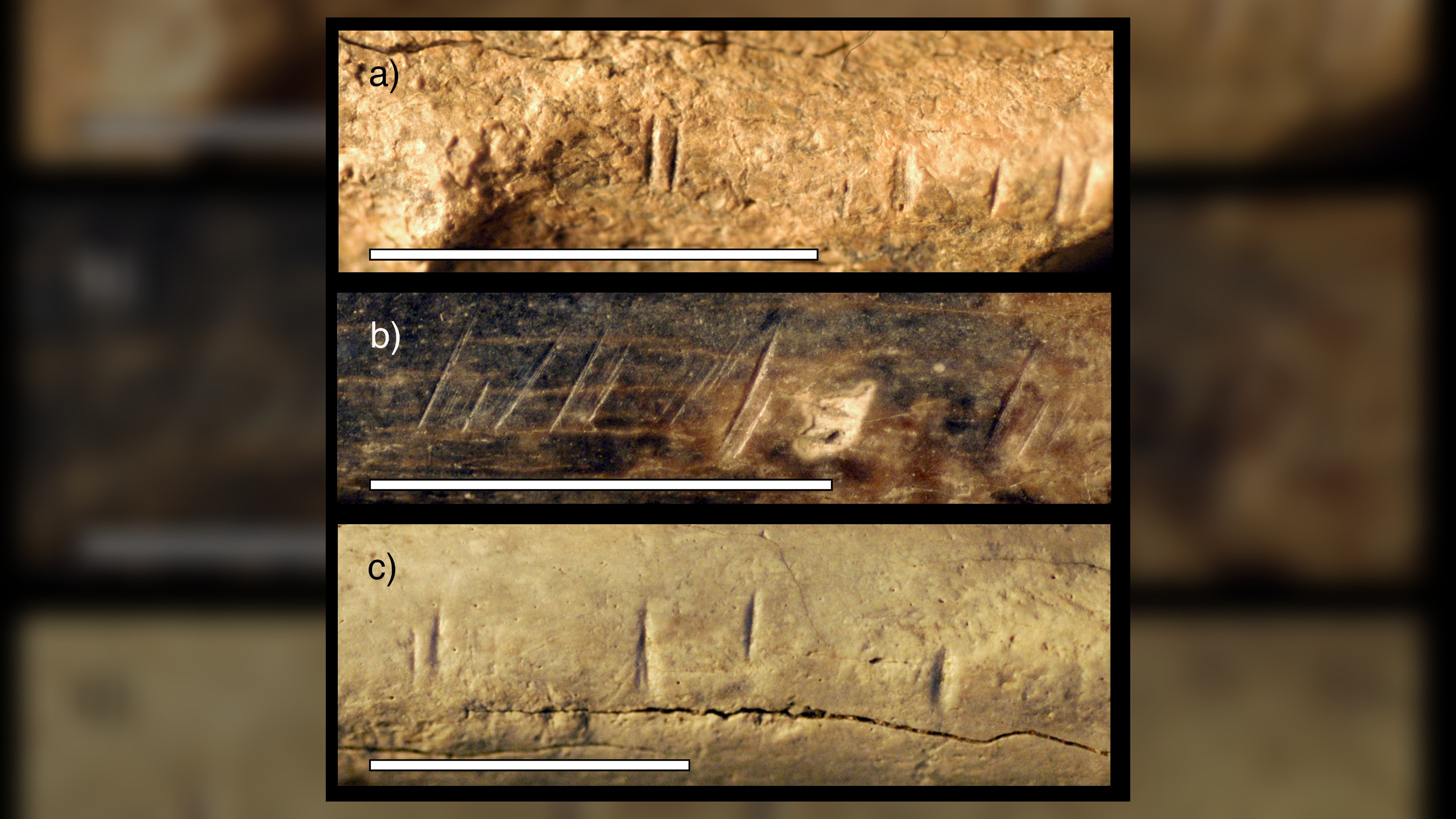

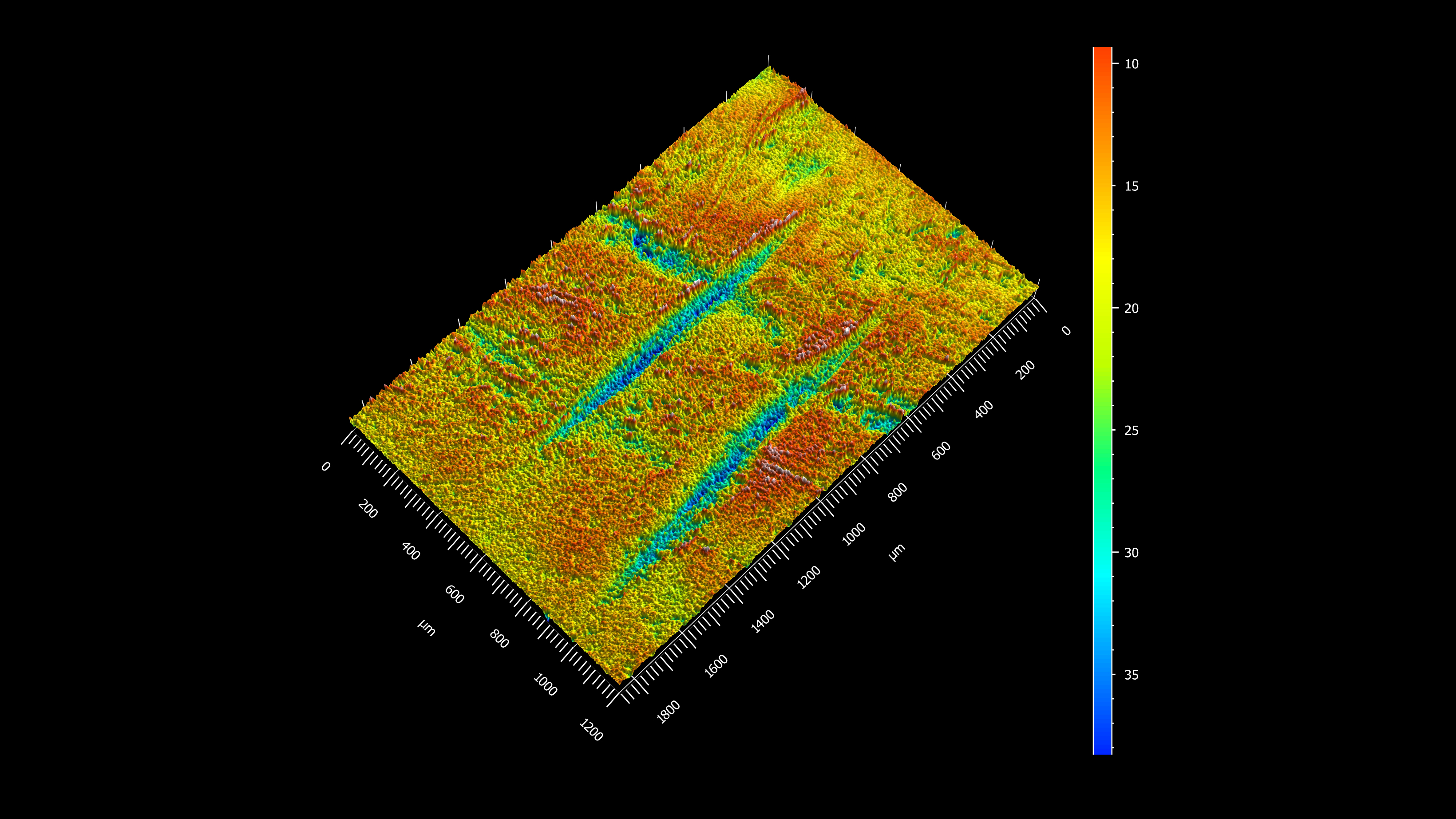

The fossilized shinbone, or tibia, was discovered in 1970 in the Turkana region of Kenya. It has nine incisions that were likely made with stone tools. The cuts are regular, oriented in the same direction and situated where a calf muscle would have been attached to the bone, suggesting they were made with the intent of stripping the flesh for consumption, the researchers found.

"The information we have tells us that hominins were likely eating other hominins at least 1.45 million years ago," study first author Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., said in a statement.

Related: What made ancient hominins cannibals? Humans were nutritious and easy prey

The newly analyzed tibia is the oldest indisputable case of hominins devouring each other, but experts are divided as to whether a roughly 2 million-year-old Homo habilis or Australopithecus skull from South Africa could be considered the oldest. Recent work argues that its "linear marks" were from natural processes rather than butchery.

Pobiner noticed the incisions while searching for bite marks from predators living during the Pleistocene (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) on fossilized bones in the collections of the Nairobi National Museum in Kenya. She was struck by their similarity with butchery marks on animal bones also unearthed in the region.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These cut marks look very similar to what I've seen on animal fossils that were being processed for consumption," Pobiner said. "It seems most likely that the meat from this leg was eaten and that it was eaten for nutrition as opposed to for ritual."

Pobiner and her colleagues also detected two dents in the bone, which they identified as bite marks from a big cat — possibly belonging to one of the saber-toothed cat species living in eastern Africa at the time. But they found no human tooth marks on the fossil.

Because the cut and feline bite marks don't overlap, the researchers can't tell which happened first or how the butchered individual died. Hunters may have come across the carcass after a big cat slaughtered it. But the location of the cuts suggests there was still flesh on the skeleton when another hominin slashed the bone to make a meal, according to the study, published Monday (June 26) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Researchers who originally examined the shinbone thought it belonged to the hominin Australopithecus boisei (also referred to as Paranthropus boisei, but it is debated whether Paranthropus is a valid grouping). A subsequent analysis then described it as a Homo erectus tibia, but the authors of the new study said there simply isn't enough information to assign the bone to a species.

The methods used to study the marks on the bone were "consistent and rigorous," said Jesús Rodríguez Méndez, a paleoecologist at the National Research Center for Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Spain who was not involved in the study.

Rodríguez Méndez agreed that these are butchery marks. "The most likely explanation is that the carcass of this hominin was eaten by other hominin(s), and that it was likely scavenged rather than hunted, although this interpretation is speculative," he told Live Science in an email.

This is the earliest confirmed case of hominins eating hominins on record, but it isn't the first. Butchery and human tooth marks on 772,000- to 949,000-year-old remains of Homo antecessor unearthed at the Gran Dolina cave site in Spain point to cannibalism as part of the species' regular diet.

There is also substantial evidence that Neanderthals ate each other 100,000 years ago.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus