Scientists glean new details of mysterious, centuries-old shipwreck submerged in Norway's largest lake

Researchers now think the boat was a local "føringsbåt" for passengers and cargo.

A shipwreck discovered during a search for dumped wartime ammunition in Norway's Lake Mjøsa has been identified as a local "føringsbåt" from up to 700 years ago. But bad weather has prevented researchers from finding out more.

The wreck, which lies at a depth of around 1,300 feet (400 meters), was found in 2022 by an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) mapping the lake for Norway's military.

The discovery caught the attention of researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) based in the city of Trondheim. But they were not able to revisit the wreck until last month.

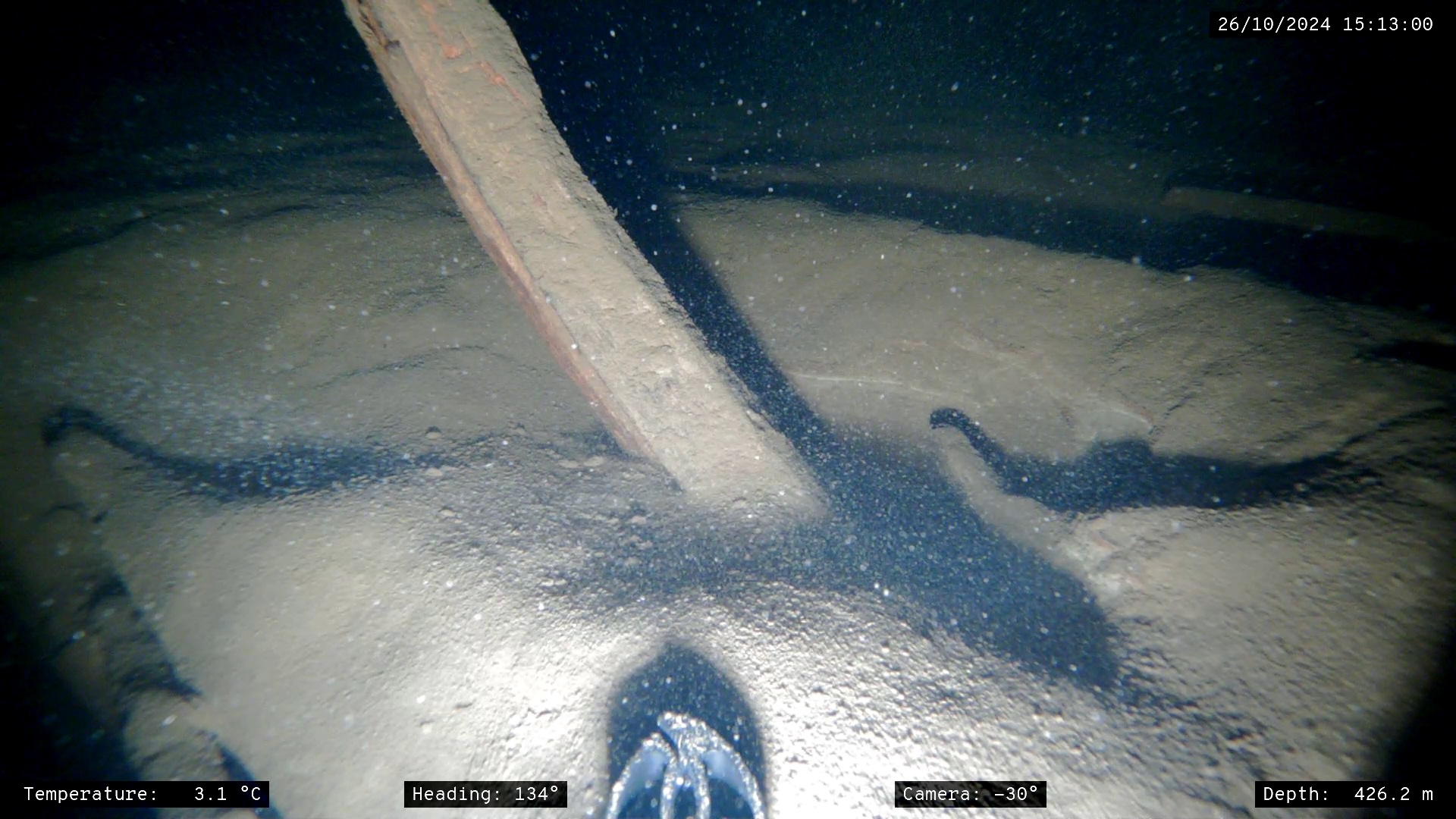

NTNU maritime archaeologist Øyvind Ødegård told Live Science that he and his colleagues explored the wreck for about an hour using a remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) tethered to a research boat on the surface. But technical issues and encroaching bad weather prevented the researchers from using the underwater drone to take wood samples for radiocarbon dating, so the wreck's exact age will remain unknown until they can return there next spring.

Several visible features of the wreck, however, indicate the vessel was built between 1300 and 1700, Ødegård said.

Related: 32 haunting shipwrecks from the ancient world

Norwegian lake

Lake Mjøsa is the largest lake in Norway and lies about 60 miles (100 kilometers) north of Oslo. It covers more than 140 square miles (360 square km), but only a few square miles of the lake bottom have been mapped. It was a vital trade route between the many prosperous communities along its shores from at least the eighth century.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ødegård said the researchers now think the mysterious vessel was a "føringsbåt" used to carry cargo and passengers. Such boats were widely used on Norwegian lakes, but their flat-bottomed construction made them unsuitable for the open sea.

The latest explorations showed this particular føringsbåt was built with an upright stern, a feature introduced in Norway after about 1300; earlier Viking ships were the same on both ends. And there are signs that it may have had a central rudder at the stern for steering, whereas Viking ships used a specialized steering oar on one side, Ødegård said.

The boat was also built with wooden planks overlaid in a "clinker" style. This traditional Scandinavian boatbuilding method was superseded by the flush planks of the "carvel" style, an innovation from the Mediterranean.

Telltale planks

The 33-foot-long (10 m) wreck in Lake Mjøsa is covered with sediments, which Ødegård thinks may have been penetrated by the sonar equipment that located the wreck in 2022. The wooden planks in the hull that can be seen are relatively wide — a sign they were cut with an ax, rather than sawed at a shipyard.

"That is an indication that this wreck is older," Ødegård said.

The 2022 discovery was made with an AUV operated by the Norwegian military, but the latest explorations used an ROV operated by the university spin-off company Blueye.

The wreck now lies on the bottom of Lake Mjøsa in deep and calm waters, but the lake surface in that area has strong currents, Ødegård said.

In addition to preventing the researchers from reaching the wreck on several occasions, the currents may have caused the føringsbåt to founder.

"It's not the calmest spot," he said. "That leads us to guess that someone had an accident while crossing the lake."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.