Scientists map the lost 'Atlantis' continent that lies off Australia

A new simulation reveals how Australia's first inhabitants migrated across Sahul, before it became modern-day Australia.

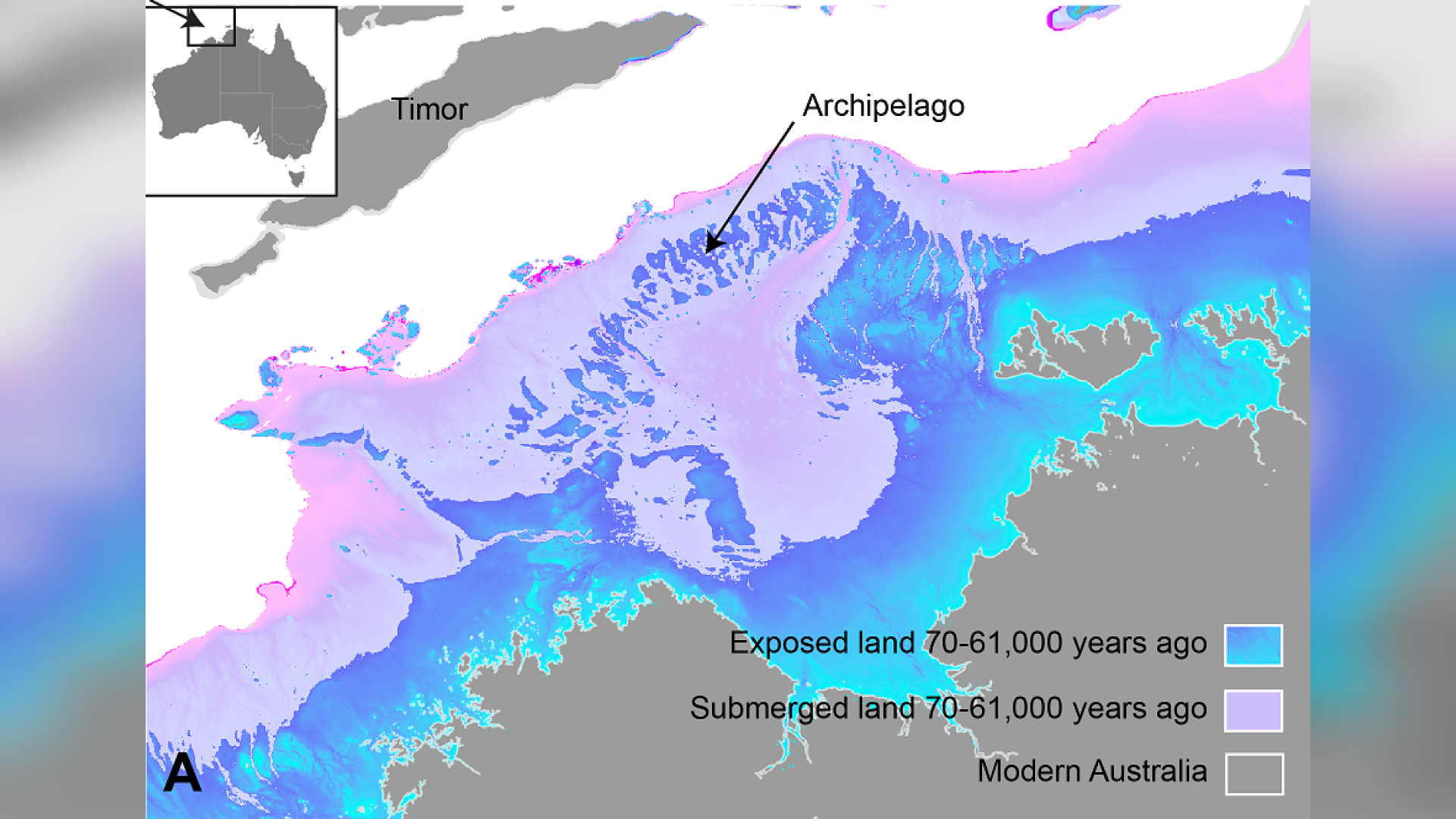

One of the most extraordinary stories of human migration unfolded around 70,000 years ago, as humans crossed from Southeast Asia into modern-day Australia, traversing a now-submerged, Atlantis-like landscape, and becoming the first people to call that land home.

A rich archaeological record provides ample evidence that this happened. But researchers have long been stumped by the details of this migration, such as how quickly that trek occurred and what routes the newcomers took across the vast territory.

Now, new research published April 23 in the journal Nature Communications sheds light on some possible answers. Intriguingly, it also helps to pinpoint potential undiscovered archaeological sites where researchers could search for new evidence.

The research looks at the vast supercontinent that was known as Sahul, a landmass that was exposed about 70,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch, when Earth was in the midst of the last ice age. Glaciation caused declining sea levels that exposed areas of submerged continental shelf connecting what is now mainland Australia to Papua New Guinea in the north and Tasmania in the south.

Sea levels remained low for thousands of years at a time, but other geological and environmental conditions would have evolved over this period. For instance, there would have been changing rainfall patterns, shifting river courses, spreading or shrinking forests and grasslands, and sediment deposition. All of these factors would have influenced the characteristics of the terrain and, therefore, how humans explored it.

The researchers used this information to develop a landscape evolution model, which simulated Sahul's changing landscape between 75,000 and 35,000 years ago. The simulation also incorporated possible migration routes from two locations in Southeast Asia — West Papua and the Timor Sea Shelf — as well as archaeological sites spread across the modern-day landscape.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dating those sites helped to pinpoint the periods when people would have been moving through those parts of the continent. Finally, the simulation incorporated estimates from "Lévy walk foraging patterns" — a type of movement that's commonly used by hunter-gatherers to find food in unfamiliar landscapes — which also helped to estimate the pace of migration.

"The new landscape evolution model allows for a more realistic description of the terrains and environments inhabited by the first hunter-gatherer communities as they traversed Sahul," Tristan Salles, an associate professor in the School of Geosciences at the University of Sydney and lead author of the study, said in a statement. The researchers ran thousands of simulations that exposed the most likely routes humans would have taken, following landscape features and the availability of food they could forage.

The researchers discovered that these routes would have taken the newcomers along the coastlines and straight through the continent's interior, following the major rivers and streams that crisscrossed the landscape at the time. The calculations showed that these intrepid humans likely traversed the landscape at a pace of about 0.71 mile (1.15 kilometers) per year, which the researchers say is relatively swift. Interestingly, the simulation showed an overlap with regions where other researchers have suggested humans may first have congregated on Sahul.

By showing where Australia's first people most likely moved, the model may even provide archaeologists with some practical insights for their work.

"There's one particularly interesting outcome from our map that shows the probability of human presence in Sahul," the study authors wrote in an article for The Conversation. "In a cost-effective way (without needing to travel across the entire continent), it could potentially pinpoint areas of archaeological significance."

The model helps to flesh out the picture of life on Sahul, where previous research has shown that up to half a million people may have once lived on its now-sunken northern shelf.

"Our study is the first to show the impact of landscape changes on the initial migration on Sahul, providing a new perspective on its archaeology," the researchers wrote. "If we used such an approach in other regions as well, we could improve our understanding of humanity's extraordinary journey out of Africa."

Emma Bryce is a London-based freelance journalist who writes primarily about the environment, conservation and climate change. She has written for The Guardian, Wired Magazine, TED Ed, Anthropocene, China Dialogue, and Yale e360 among others, and has masters degree in science, health, and environmental reporting from New York University. Emma has been awarded reporting grants from the European Journalism Centre, and in 2016 received an International Reporting Project fellowship to attend the COP22 climate conference in Morocco.