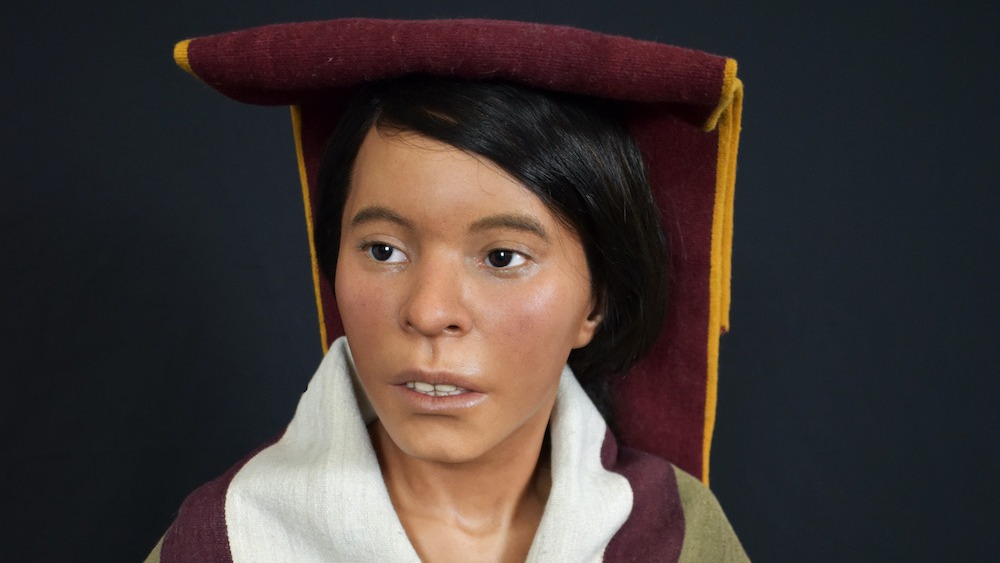

See how an Incan 'Ice Maiden' comes alive in this step-by-step guide to creating a facial approximation

Forensic artist Oscar Nilsson explains how he created a facial approximation of an Incan "Ice Maiden" 500 years after she died.

Creating a facial approximation is no easy task and can take upward of hundreds of hours to create. Case in point: The facial reconstruction of an Incan girl who died 500 years ago on the summit of a mountain in Peru, likely in a sacrificial ritual. Decades after a team of archaeologists discovered her frozen mummified body in 1995, Oscar Nilsson, a forensic artist based in Sweden, created a life-like facial reconstruction of the teenager. All told, it took Nilsson nearly 400 hours to make the facial approximation of the "Ice Maiden" (also known as "Juanita") using a blend of technology mixed with hands-on techniques that used clay and silicone to create the final reconstruction.

Here, Nilsson explains step by step how he brought the "Ice Maiden" to life centuries after her death.

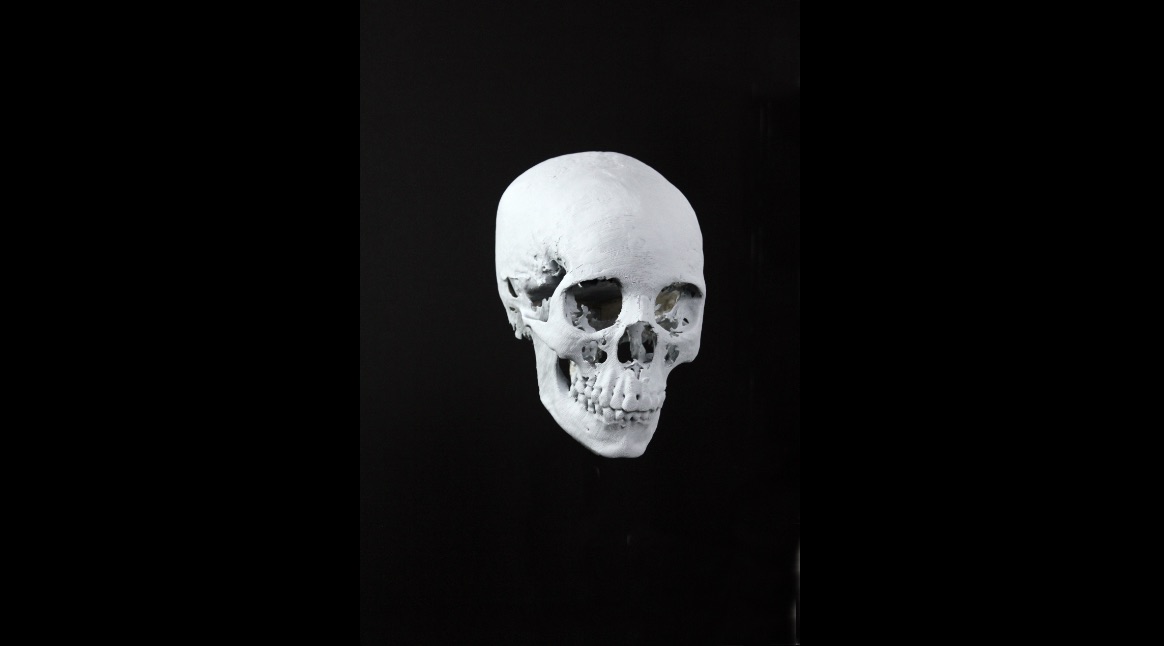

Step 1

To create the approximation of Juanita, Nilsson began with computed tomography (CT) scans of the girl's skull and body, which were provided by archaeologists. Nilsson regularly collaborates with researchers on his approximations to ensure that everything is accurate, and this case was no different. Nilsson views a CT scan, which creates a virtual 3D model, as a "scientific frame" that gives him the measurements he needs to build the face's shape.

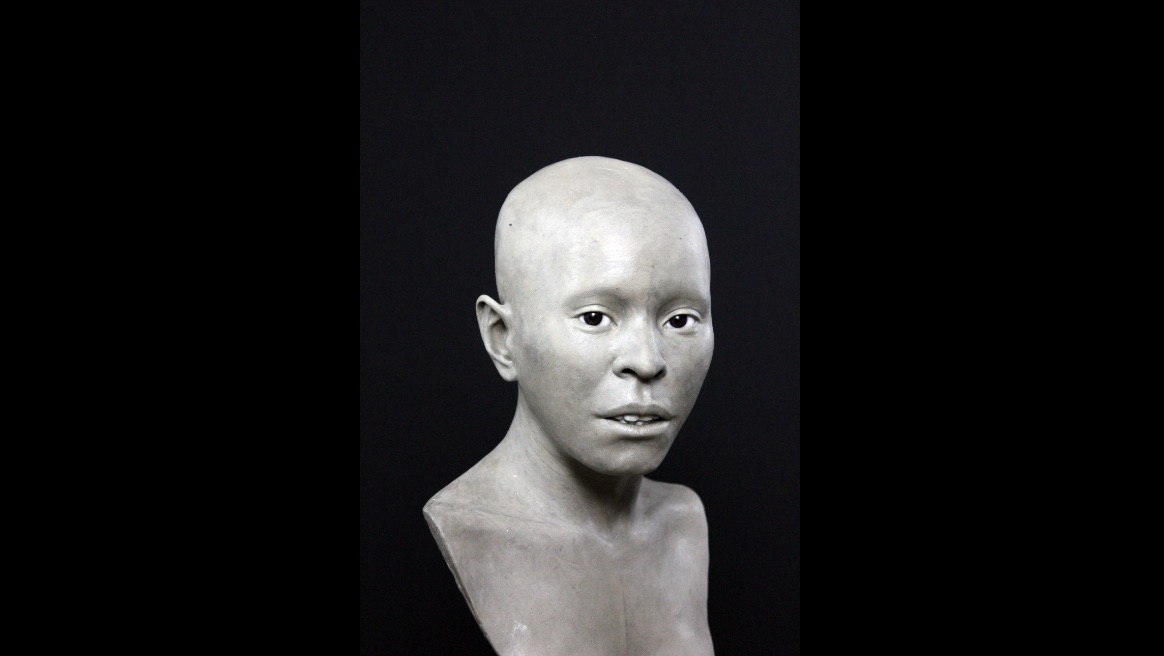

Step 2

Next, he uses data pulled from global databases containing scans of living people (often called donors). This information helps him determine features like the positioning and thickness of a subject's facial muscles, fat and skin. Nilsson can narrow his database search to include only donors who have similar characteristics to his subject, such as sex, age and ethnicity. This ensures that the features are more similar.

Step 3

With data points in hand, Nilsson transferred the measurements to wooden pegs and used clay to start building the muscle and tissue layers that form the foundation of the girl's face, such as the nose, eyes and mouth. This technique of rebuilding the muscles of the face layer by layer is called the American Method and is one of the more popular forms of reconstruction used by forensic artists. To get the features correct, Nilsson can take cues from his subject's nasal cavity, eye orbits and teeth.

Step 4

Now comes the fun part for Nilsson, which is when he uses a bit more creative liberty in his work by creating what he calls the "small expressions" that make the face really come to life. In this step, he still prioritizes scientific correctness but can create subtle expressions on Juanita's face. For example, he "wanted her to look both scared and proud, and with a high sense of presence at the same time," he told Live Science.

Step 5

The last step to really bring the reconstruction to life is to add in color and texture. Nilsson used pigments to color Juanita's skin so that it looked real. He also used real human hair, which he painstakingly inserted individually, strand by strand. To inform his work, he used a DNA analysis provided by archaeologists that showed that she would’ve had dark features. Lastly, he worked with local artisans to create replicas of her ceremonial tunic and headpiece that were similar to what she wore when archaeologists found her remains.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.