South African rock art of mystery creature 'strangely flexed like a banana' might be tusked reptile that predated dinosaurs

Cave art created by the San, the indigenous hunter-gatherers of South Africa’s Karoo region, may have been inspired by fossils of long-extinct reptiles.

A mysterious animal painted on a cave wall in South Africa's Free State Province has long baffled scientists. Is it a walrus? It looks like one, but there are no such animals in Africa. Some cryptozoologists — people who look for legendary animals like the Loch Ness Monster – have suggested the painting might depict a sabre-toothed cat.

What is known is that the painting was made by the San, the indigenous hunter-gatherers of South Africa's Karoo region. The San had a profound knowledge of their environment, which they masterfully depicted in their rock art.

What's often overlooked, though, is that their environment also contained artefacts from an ancient past: the San lived and hunted among fossil footprints, bones, skulls and teeth of long-extinct reptiles. In recent research with my colleagues, we showed that the San discovered dinosaur bones in Lesotho, which borders the Free State. They also painted dinosaur footprints on cave walls.

Now, in new research, I suggest that the mysterious animal depicted on the Free State cave wall is another extinct species — a dicynodont. Dicynodonts were first described in the scientific literature in 1845 by Sir Richard Owen, a British palaeontologist and anatomist. They were the first in a long series of mammalian ancestors discovered in southern Africa, which demonstrated that mammals are descended from a peculiar kind of reptiles called the therapsids.

The painting was made, at the latest, in 1835, which is when the San left the area. But it could be much older as the San have inhabited the area for thousands of years. This means that this dicynodont was depicted at least ten years before the species was officially discovered and named. The San already knew about dicynodonts before western scientists did. This implies a deeply rooted but almost completely forgotten indigenous palaeontology of Karoo fossils in southern Africa. It also implies some level of pre-scientific inquiry about fossils and attempts to reconstruct extinct animals before western scientists did.

San paleontologists

The southern African Karoo area, including parts of the Free State Province, is packed with millions of fossils. Most of them belong to dicynodonts. These mammalian ancestors lived about 265 million to 200 million years ago. There were many species and great diversity among those species, with body size ranging from mouse-like to rhino-like. They were the dominant species of their time, much like antelopes dominate the Serengeti today.

As such, they have left a rich fossil record, including conspicuous and often very large skulls and teeth that litter the ground where Karoo rocks are exposed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A San myth recalls that "enormous brutes", now completely extinct, used to roam southern Africa a very long time ago. This story may refer to these dicynodont fossils, which the San might have discovered and tried to interpret.

The tusked-animal of La Belle France

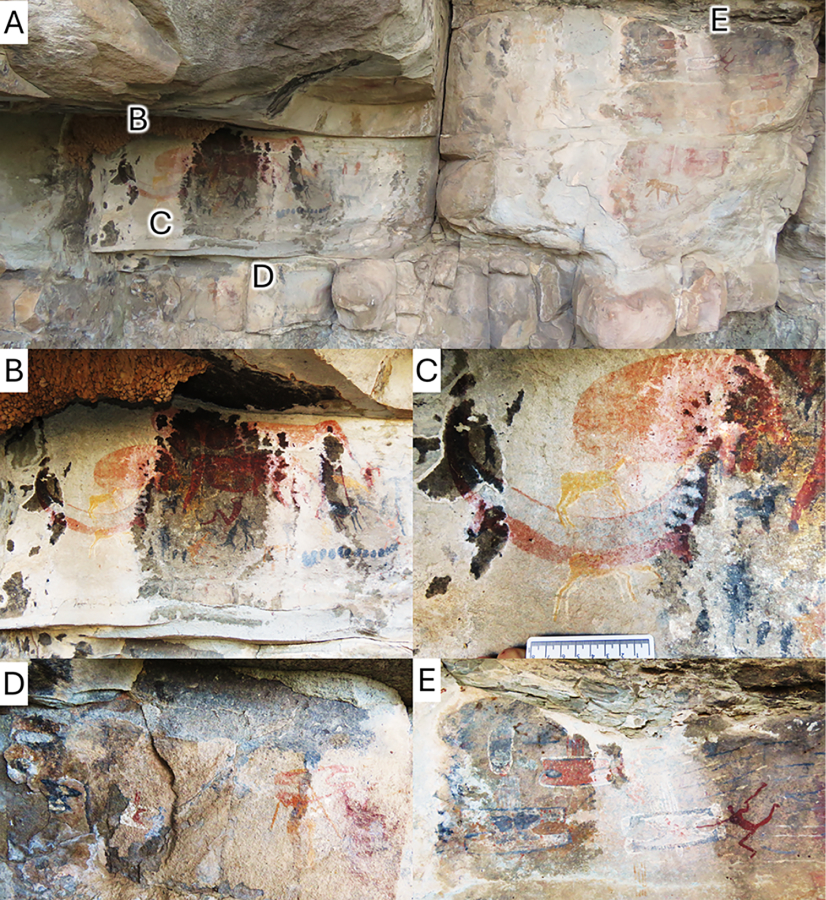

For my new paper, I studied the curious painting, known as the Horned Serpent panel, that has baffled so many. It is on a cave wall at a farm called La Belle France. The rock art depicts an animal that sports two tusks. The two enlarged teeth point downwards, which is unlike any tusk-bearing animal that lives today in Africa.

I considered other possibilities — might it be a pig, a warthog or an elephant? — but excluded these. The only animals alive today that have two large, downward pointing tusks like those of the La Belle France animal are walrus. But no walrus has ever lived in sub-Saharan Africa.

Dicynodonts, however, did — and their fossilised skulls have conspicuous tusks. I found many fossils in the immediate vicinity of the painting, which supports my hypothesis that the San discovered dicynodont skulls and bones in the area, then drew a reconstruction of the living animal as they imagined it.

In addition, the body of the tusked animal from La Belle France, as painted by the San, is strangely flexed like a banana, a pose that is commonly encountered on fossil skeletons and is called the "death pose" by palaeontologists. Its body is also covered with spots, not unlike the mummified dicynodonts found in the area whose skin is covered with bumps. This is consistent with the San discovering one or many dicynodont skulls and complete skeletons in the field and depicting them in their rock art.

"Rain-animals"

Researchers have previously established that tusked animals were an example of "rain-animals", a fantastic creature of the San pantheon.

"Rain-animals" can take many forms, usually inspired by real life aquatic animals, but this is the first time it would have been inspired, at least in part, by a fossil species. It would make sense to use dicynodonts for rain-making rituals because they are extinct and, as such, belong entirely to the "realm of the dead", which San shamans explored during trance states.

Though we don't know for sure, there's a chance that the San considered fossils to have magical potency. This would imply that they integrated fossils into their belief systems and opens up new avenues to better understand their rock art and culture.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

I am a vertebrate palaeontologist and Palaeobiologist with special interest in the study of the evolution of endocranial structures and sense organs in extinct mammals and therapsids (mammal-like reptiles) using X-ray imagery on their fossilized skulls.