Stone Age 'CSI': Archaeologists identify a family killed in a house fire nearly 6 millennia ago

Human bones discovered in a house that burned down 5,700 years ago are providing archaeologists "CSI"-style clues about the deaths of seven people in prehistoric Ukraine.

Burnt and battered human bones from 5,700 years ago hint at a brutal end for a group of Stone Age people who likely died in a house fire in what is now Ukraine, a new study finds.

But why two of the people had violent head injuries and why one died a century later than everyone else remain unsolved mysteries.

"We can only speculate whether there was a connection between the fire and the act of deadly violence, i.e. killing the people in the house, leaving their corpses, and setting the house on fire," Katharina Fuchs, a biological anthropologist at Kiel University in Germany, and colleagues wrote in a study published Wednesday (Dec. 11) in the journal PLOS One.

In 2004, archaeologists discovered nearly 100 pieces of human bone in a prehistoric house at Kosenivka, an archaeological site about 115 miles (185 kilometers) south of Kyiv. Kosenivka preserves the remains of a prehistoric "mega-settlement" created by the agrarian Cucuteni-Trypillia societies (CTS), who lived throughout what is now modern-day Romania, Moldova and Ukraine from 4800 to 3000 B.C. These settlements consisted of public buildings and family houses, many of which were deliberately burned down when people left.

But the discovery of human bones within one of the burned houses at Kosenivka surprised archaeologists, who undertook the new detailed study to figure out what happened.

Related: Strange pile of Stone Age skulls unearthed in Italian village baffles archaeologists

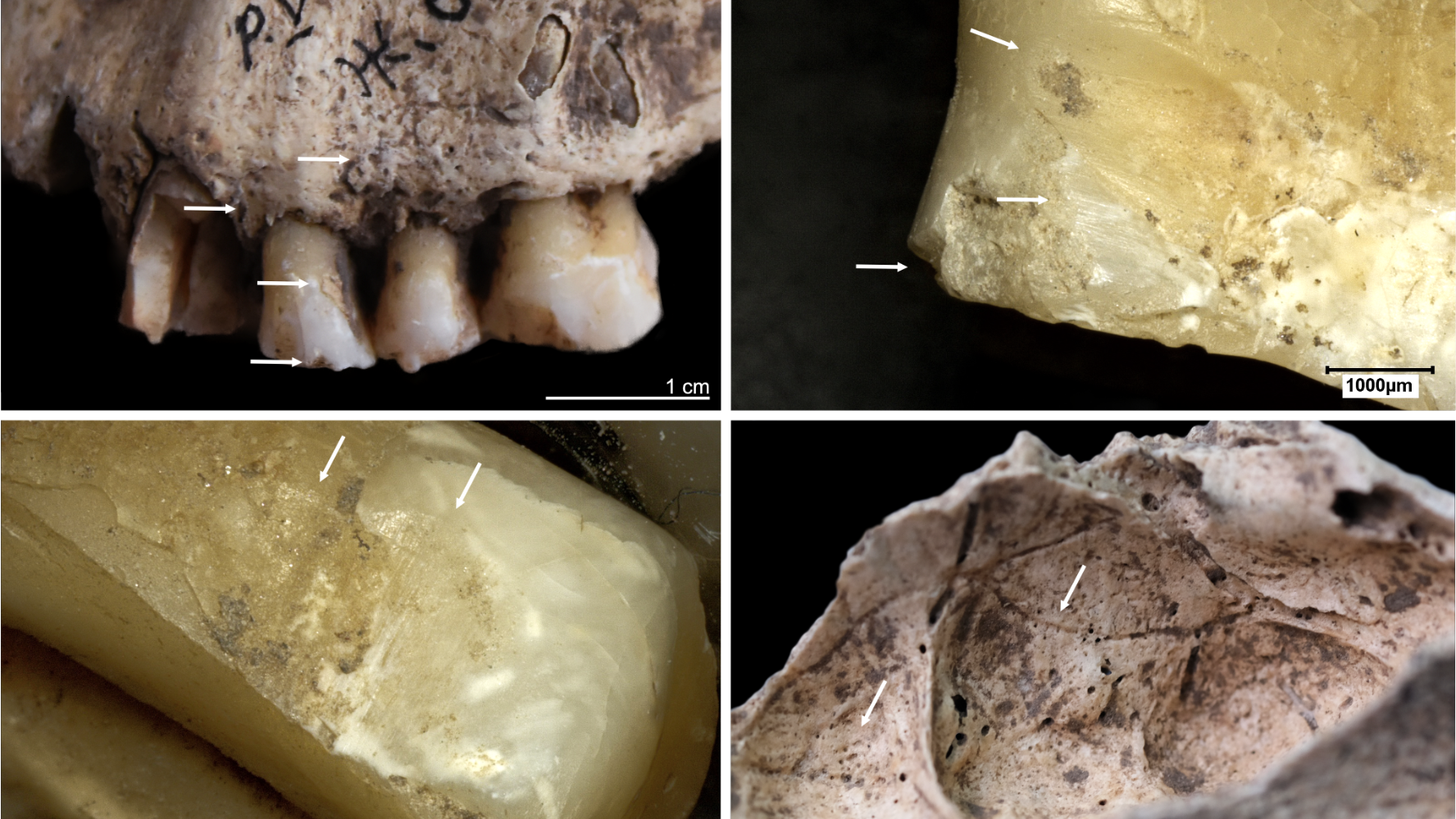

A close look at the bones revealed the remains of at least seven people: two children, one adolescent and four adults. Four of the skeletons were found inside the destroyed house and were heavily burnt, while the other three were unburned and found outside the dwelling. The researchers discovered that two of the adults had suffered violent head trauma just before their deaths, setting up a 5,700-year-old forensic mystery.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To investigate this cold case, the research team used radiocarbon dating to determine that six people, possibly a family, likely died between 3690 and 3620 B.C., while the seventh — an unburned adult — died roughly 130 later, after the house burned and was abandoned. Then, they looked closely at the bones' fracture patterns and discoloration to figure out that the bones were scorched while still fresh.

Given the contemporaneous dates of death and the evidence of burning, the team deduced that three people may have died inside the burning house, while others may have been overcome by smoke inhalation or carbon monoxide poisoning and died just outside the house. However, this analysis did not reveal further information about the cause of the skull injuries.

Regardless of how these six Stone Age people died, it is clear that the house and bodies were completely covered with soil and debris within a matter of months and that part of someone else's skull was placed on top a century later, the study authors explained.

The isolated skull fragment could be a deliberate ritual deposition, the researchers wrote, and the whole collection of bones could be the result of a complex, multistage burial tradition. Unfortunately, Fuchs told Live Science in an email, "although they left us a tremendous amount of archaeological material, there are still so many things we do not know — for instance, how they treated their dead."

"It seems reasonable that the individuals recovered from Kosenivka were killed during a raid and that their house was lit on fire during the conflict," Jordan Karsten, an archaeologist at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "Previous explanations [for burned CTS houses] have focused on ritual house destruction through intentional burning, but these results suggest that intergroup conflict might better fit the data."

Economically, it makes little sense to burn down a home full of food, ceramics, tools and ritual items, and the CTS people lived in a forested steppe area near nomadic pastoralist groups.

"Rather than destroy their own homes, doesn't it seem just as likely that these neighbors would do it?" Karsten said.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.