Stone tools and camel tooth suggest people were in the Pacific Northwest more than 18,000 years ago

One of the earliest North American human occupation sites, dating to more than 18,000 years ago, was discovered in Oregon.

Stone tools and the teeth of an extinct camel and bison discovered in central Oregon show that people were living in North America 18,250 years ago, new research finds. Although this is not the earliest date for human occupation of the Americas that has been proposed, the finding, which is not yet published in a peer-reviewed study, appears to be thousands of years older than any other archaeological site in Oregon.

Archaeologists made the discovery at the site of Rimrock Draw, which includes a rock shelter that researchers have been excavating since 2011 under a partnership with the Bureau of Land Management. Initial investigations found stone tools from the Paleo-Indian period (15000 B.C. to 7000 B.C.), but the geology of the site suggested that there were sediment layers dating to even earlier.

Although they expected to find old bones and artifacts, the archaeologists were startled by a stone tool with dried bison blood, which was discovered under a layer of volcanic sediment from the eruption of Mount St. Helens 15,400 years ago. This meant that humans were butchering ice age game in the Pacific Northwest far earlier than assumed. The oldest directly-dated evidence of humans in the U.S. comes from Paisley Caves in Oregon, where researchers studied coprolites — preserved poop — to conclude they came from humans and were about 14,200 years old.

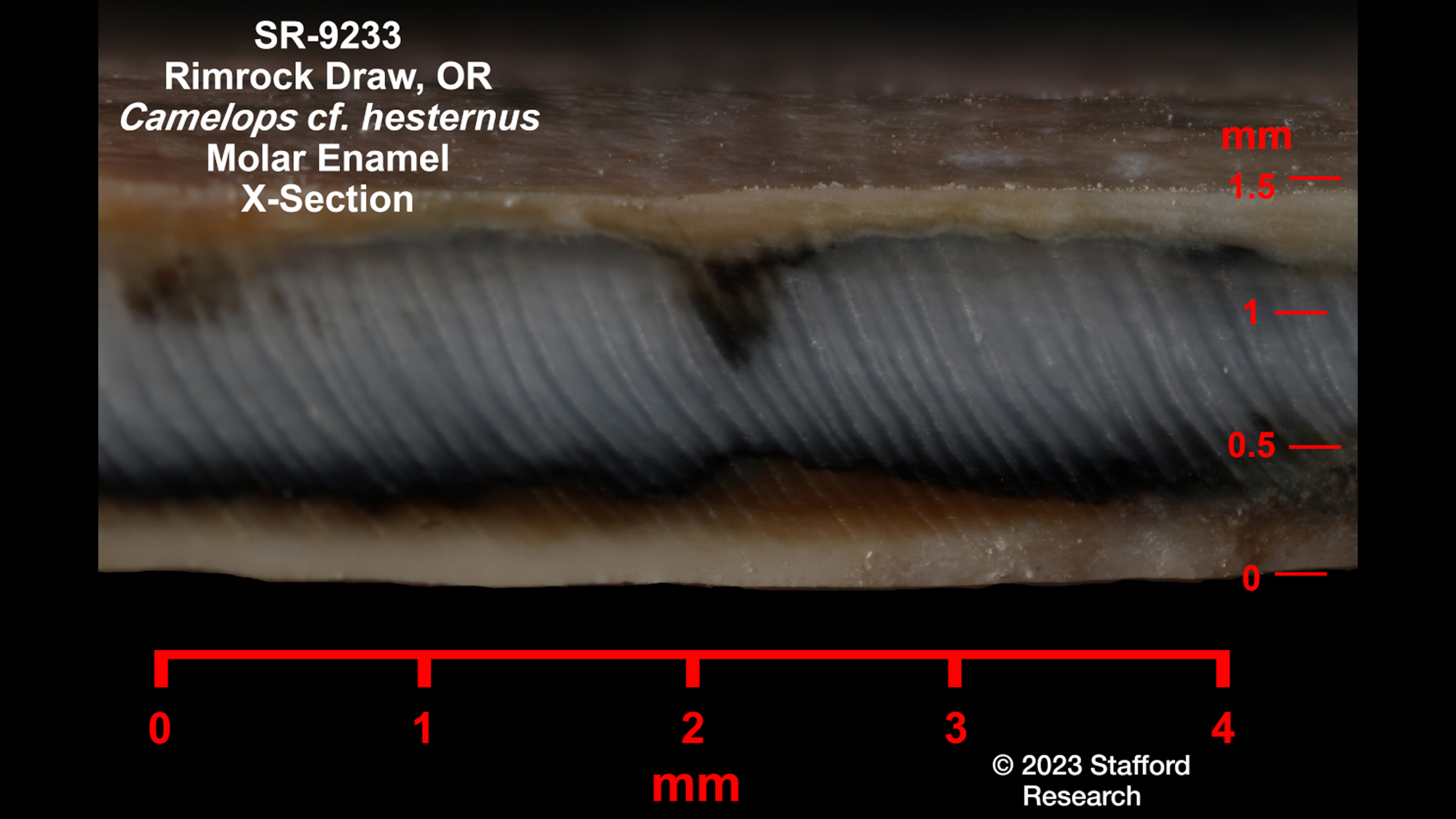

Given this already surprisingly old date based on geological layers, the researchers decided to directly test some of the remains — including the tooth enamel of a Camelops, a now-extinct camel — to obtain solid dates.

"We ran the first date on the Camelops tooth enamel in 2018," Patrick O'Grady, an archaeologist at the University of Oregon's Museum of Natural and Cultural History who led the research, told Live Science in an email. When it came back with an extremely old date, he knew he would need additional proof.

Archaeologists have been studying how and when people migrated to the Americas for over a century. While researchers used to assume that no humans were on the continent until about 13,000 years ago — when they walked over the Bering Land Bridge during the last ice age — both genetic and archaeological evidence have been pushing that date back further and further. However, these dates have spurred controversy.

For example, a set of human footprints in New Mexico may date to 23,000 years ago, and a newly reported find of human-modified sloth bones from Brazil dates to 27,000 years ago, both well before the peak of the ice age about 20,000 years ago. However, many archaeologists still find these lines of evidence for human presence circumstantial and would prefer to see directly dated skeletons or genetics to confirm these dates.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

O'Grady and his team took another sample from the camel tooth, as well as one from a bison tooth. When they were carbon-dated earlier this year, all of the dates agreed: Rimrock Draw was almost certainly used by humans 18,250 years ago.

"Now that we have confirmation [of the date] plus additional support from a second sample, we feel comfortable with moving forward on the peer-reviewed article this fall," O'Grady said.

Paulette Steeves, an archaeologist at Algoma University in Canada who was not involved in the research, said Rimrock Draw is an interesting site. "Archaeologists that work on sites that are older than 11[,000] or 12,000 years are extremely careful with their dating and their work because of the historical pushback on older sites," she told Live Science in an email.

Part of the Rimrock Draw publication will be focused on the dating methods used to produce the early date. Thomas Stafford, a geoscientist and founder of Stafford Research Laboratories who is involved in the research, told Live Science in an email that "the enamel was easy to 14C date" because "mechanically, enamel dating is not complicated." Carbon-14 or radiocarbon dating is often considered the gold standard in archaeology; accurate for dates as far back as 60,000 years ago, the method measures the half-life or decay of carbon in organic remains.

Where it gets difficult, Stafford said, is in understanding the geology in which the sample was found; limestone can throw off the carbon dating of an enamel sample, making it too old, while too much rain or groundwater infiltrating a sample can make it seem younger than its true age. But Rimrock Draw is basalt, rather than limestone, and Stafford ruled out additional contamination because of the volcanic ash that protected the camel and bison bones.

Repeated carbon dating over the span of five years and over different parts of the enamel helped Stafford confirm his findings. "I concluded the ages measured on camel and bison enamel were accurate and not affected by foreign carbonates younger or older than the teeth," he said.

Steeves is confident that additional, potentially much older sites will soon be found in North America.

"After all, people did not just fall out of a plane," she said. "They would have been throughout the area. That's what people need to look at next — how many other sites have been excavated in that area that have these older dates."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.