Strange pile of Stone Age skulls unearthed in Italian village baffles archaeologists

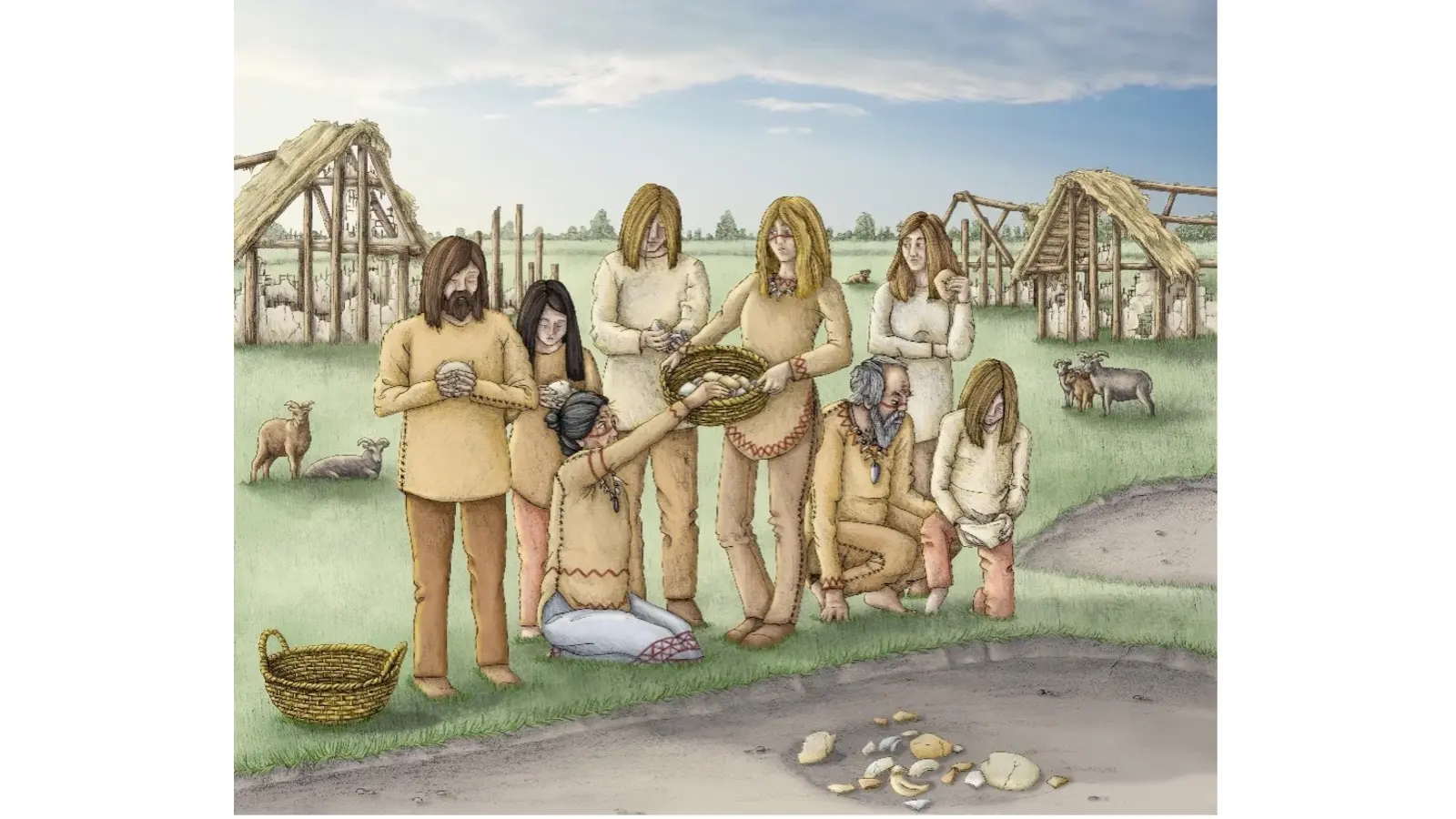

At least 15 human skulls at a Neolithic site in Italy may represent the group's collective ancestors, although archaeologists aren't certain.

Archaeologists have discovered a pile of 15 human skulls in a Neolithic village in Italy. The bones were worn and broken, but there was no evidence of violence, leading the researchers to suspect the heads were regularly handled as part of an ancient ancestor ritual.

Although human bones are often found in archaeological excavations of burial areas, this particular collection of skulls is unique because it was found inside a building, Jess Thompson, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, told Live Science in an email.

In a study published Nov. 13 in the European Journal of Archaeology, Thompson and colleagues wrote that the skull mound was found at the site of Masseria Candelaro, a prehistoric village in the Italian province of Puglia. Radiocarbon dates from some of the 400 bone fragments range from 5618 to 5335 B.C., suggesting the skulls were from Neolithic people who died over the span of nearly three centuries. Most of the skulls appeared to be male.

Masseria Candelaro was a small village encircled by concentric ditches. Within the village, excavators found a sunken feature they called Structure Q, which had layers of both domestic and ritual artifacts inside. The skull cache was found in one of the top layers and lightly covered with soil, suggesting the bones were abandoned rather than buried. Given that Structure Q was not a cemetery, finding bones there is unusual, Thompson said.

Because the skulls did not have cut marks or other evidence of violence, the research team ruled out that these were the heads of enemies collected as trophies. Rather, the way the skulls were broken suggested they were retrieved from burials, amassed by descendants and actively handled over several generations in some kind of ancestor ritual.

Related: Puzzling patchwork skeleton in Belgium contains bones from 5 people spanning 2,500 years

"We certainly think that human bone had a specific kind of meaning, and perhaps was understood to be an efficacious or potent substance, given the regularity with which it was interacted with," Thompson said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's unclear what the Neolithic people were doing with their ancestors' bones. It may have been a sort of display, Thompson said, "even though we didn't find any modifications suggesting they were suspended or attached to anything."

In the end, the final placement of the skulls in Structure Q was unlikely to have been nefarious. Instead, it may have been a way of "decommissioning" the powerful and symbolically charged bones by taking them out of circulation and transforming them into "ex-ancestors," the research team concluded.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.