'Stunning' discovery reveals how the Maya rose up 4,000 years ago

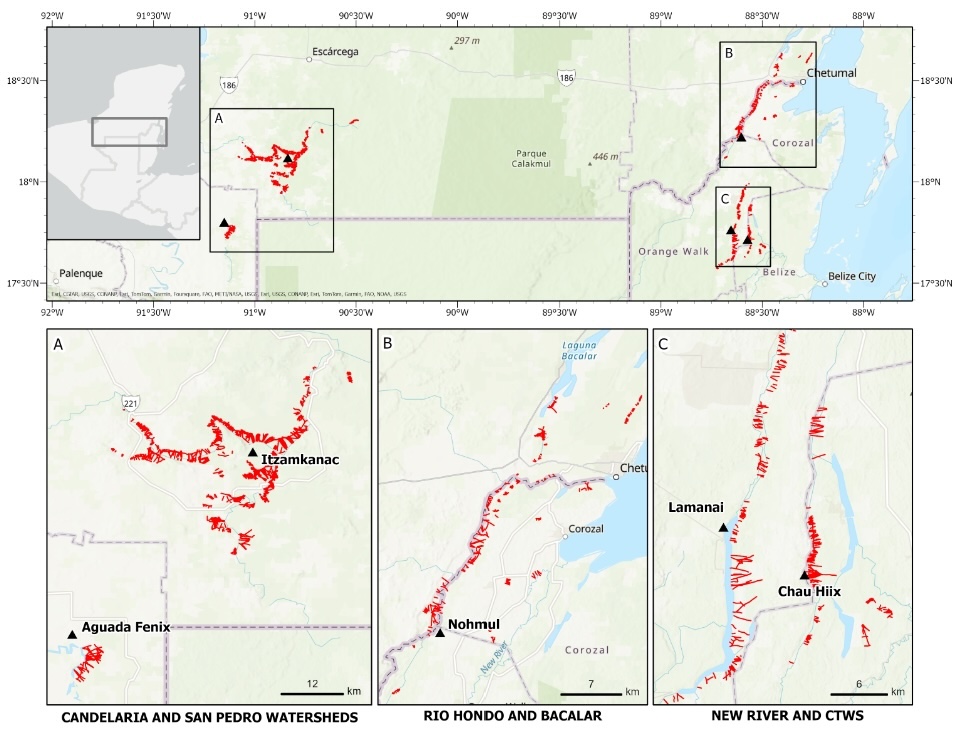

The discovery of complex fish trapping networks from 4,000 years ago hint at how the Maya rose up as a civilization in Central America and what is now southern Mexico.

A vast array of ancient fish-trapping facilities created by the direct ancestors of the Maya has been discovered in Belize.

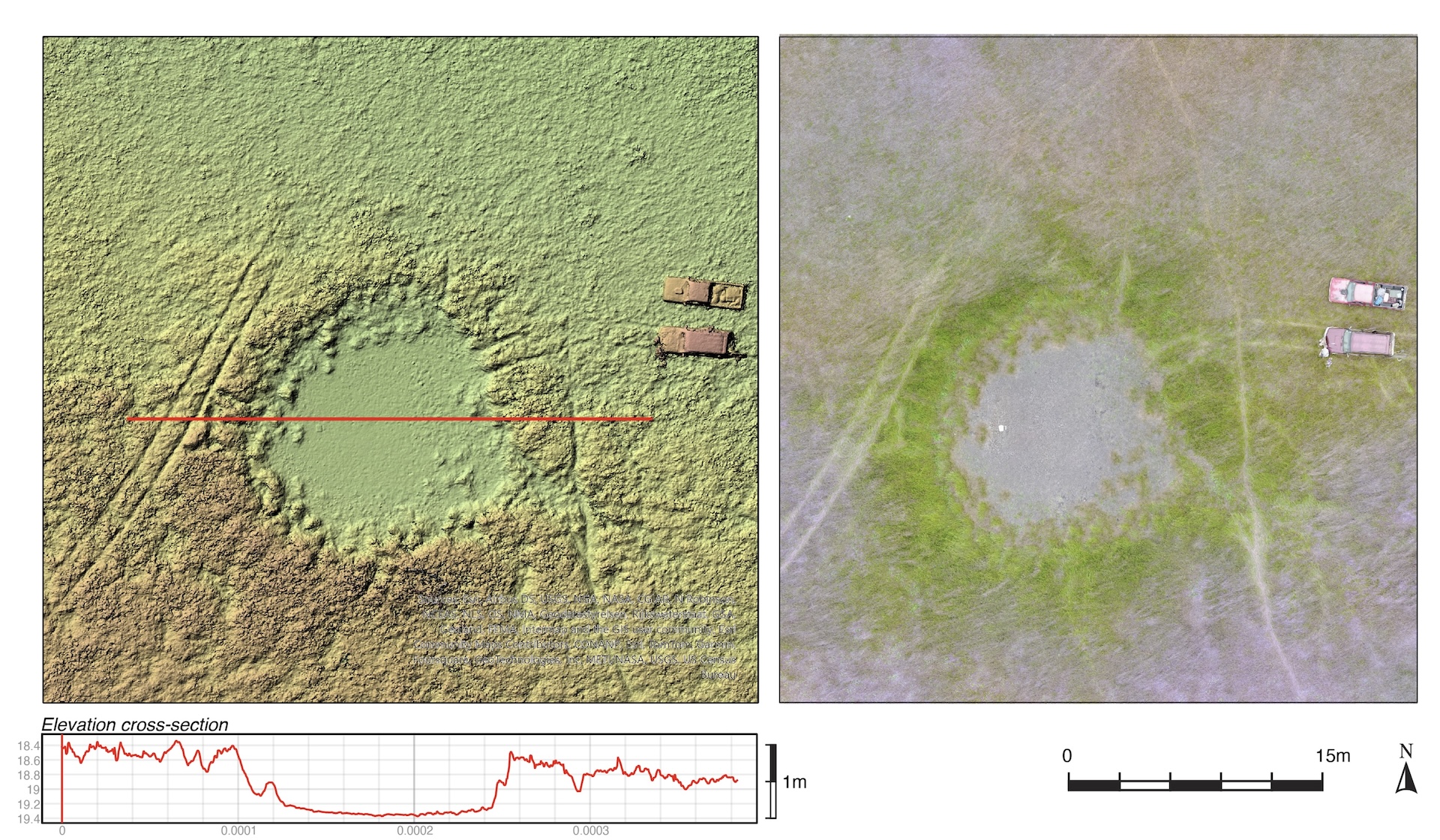

The facilities were capable of capturing enough fish to feed up to 15,000 people a year. They consisted of a network of canals and ponds that guided fish into areas where they could be easily caught.

Hunter-gatherers constructed these complex networks about 4,000 years ago, during the Archaic period, a time before people in the region were practicing agriculture on a large scale, scientists wrote in the study, published Nov. 22 in the journal Science Advances.

"This is the earliest large-scale Archaic fish-trapping facility recorded in ancient Mesoamerica," the team wrote in the paper. The success of these hunter-gatherers appears to have helped lead to the formation of the Maya, a civilization that later came to dominate the Maya Lowlands in Central America and modern-day southern Mexico.

These fish-trapping facilities would have encouraged people to gather and develop permanent settlements and, later, cities. "It seems likely that the canals allowed for annual fish harvests and social gatherings, which would have encouraged people to return to this area year after year and congregate for longer periods of time," study co-author Marieka Brouwer Burg, professor of anthropology at the University of Vermont who is co-director of the team, said in a statement.

"Such intensive investments in the landscape may have led ultimately to the development of the complex society characteristic of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization, which subsequently occurred in this area by around 1200 [B.C.]," Brouwer Burg said.

Related: Lasers reveal Maya city, including thousands of structures, hidden in Mexico

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At the time the fish-trapping facilities were built, the region was becoming drier and people may have been dealing with droughts, the team wrote in the study. This may have encouraged people to come together and build the facilities to ensure they had enough to eat.

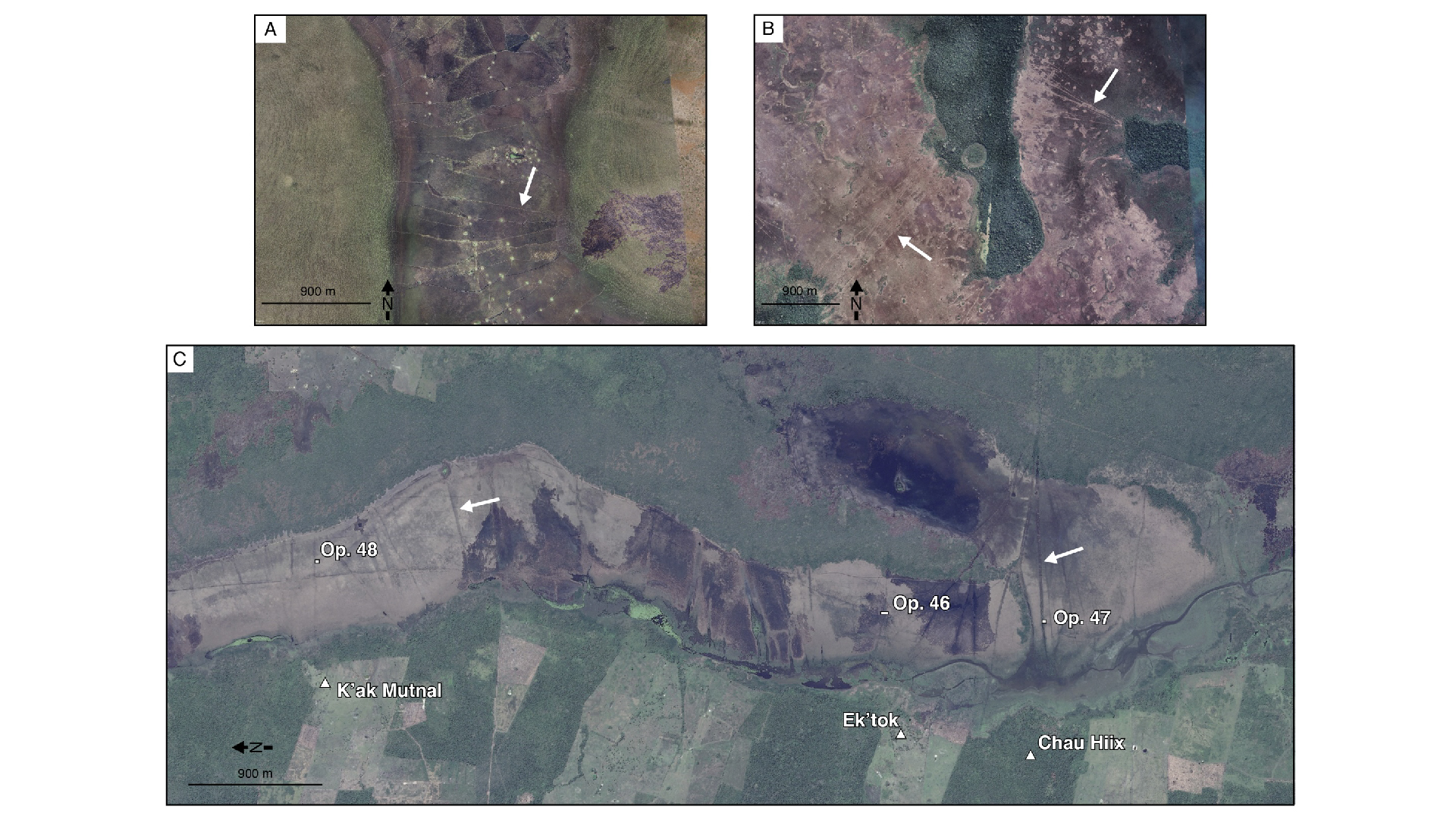

The team used satellite images and aerial images taken by drones to detect the canals and ponds. They also conducted excavations and radiocarbon dated organic sediments and charcoal to determine when the fish trapping facilities were built.

The Maya continued to use these fishing facilities in Formative times (circa 2000 B.C. to A.D. 200), the researchers wrote in the study.

"Honestly, this discovery is stunning," Thomas Guderjan, an anthropology professor at the University of Texas at Tyler, told Live Science in an email. "We have always thought of large-scale land modification projects as being something that occurred in the Maya classic period," or roughly A.D. 250 to 900, Guderjan said.

The research may encourage scholars to reconsider what the Maya were like around 4,000 years ago, Guderjan, who was not involved in the study, added.

Nicholas Dunning, a geography professor at the University of Cincinnati who has studied the Maya extensively, also praised the research.

"Over the past several decades, quite a few scholars of the ancient Maya, including myself, have suggested that aquaculture may have played an important role in the development of Maya civilization," Dunning told Live Science in an email. "However, the present study is the first that I know of to specifically attempt to test this hypothesis." The study "is an important work in helping scholars of the ancient Maya understand the origins of sedentary society in the region," he added.

Live Science contacted the research team but has not heard back at time of publication. In their paper, the scientists said they plan to continue their research in the region.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.