Teotihuacan's 'Pyramid of the Moon' is aligned with the solstice sun, researchers argue

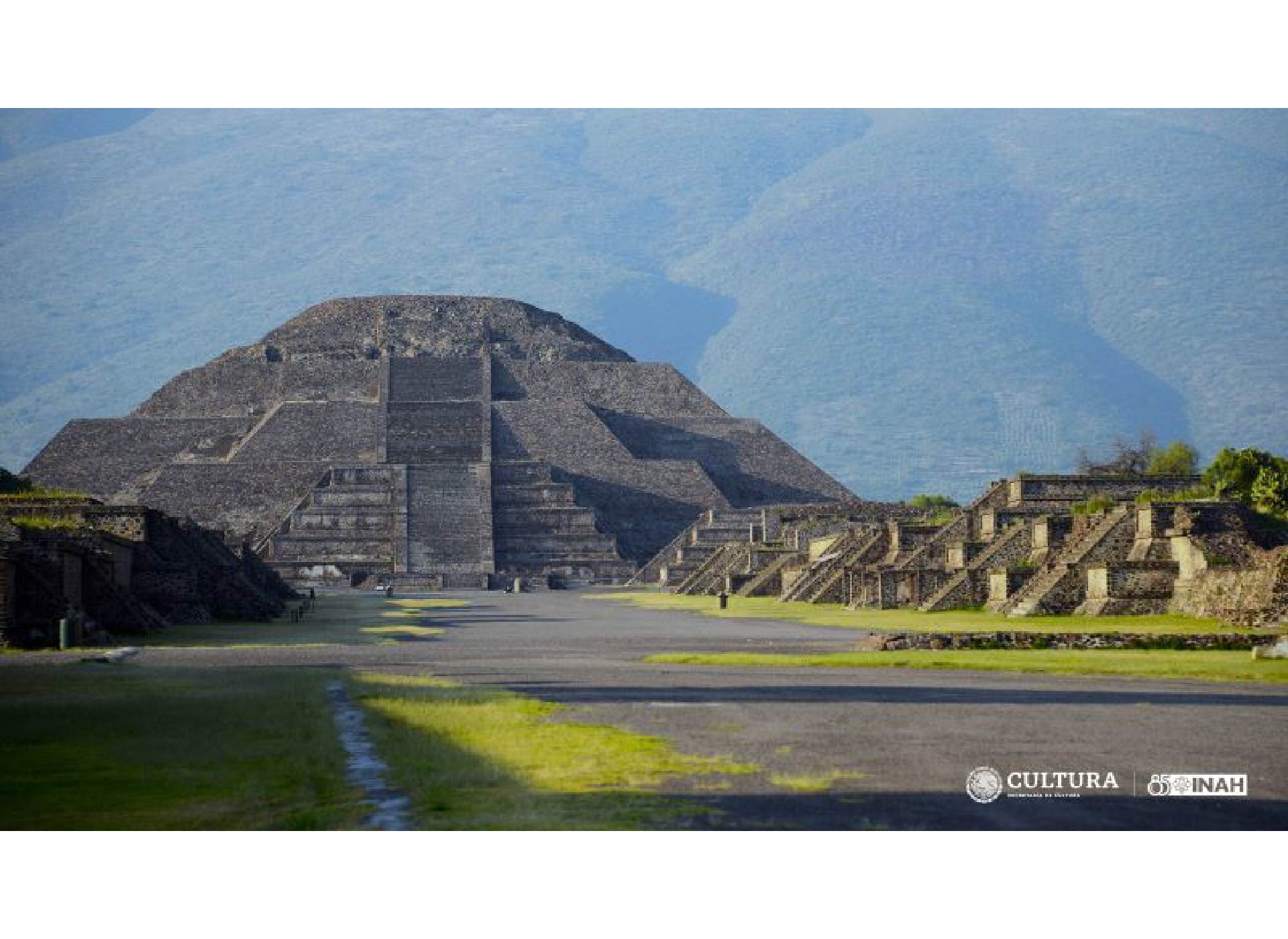

The "Pyramid of the Moon" in Teotihuacan, an ancient city in Mexico, may align with the solstice sun, a team argues.

The "Pyramid of the Moon" at Teotihuacán, the site of an ancient city near modern-day Mexico City, is aligned with the sun on the summer and winter solstices, a research team in Mexico says. However, not all experts agree with the assessment.

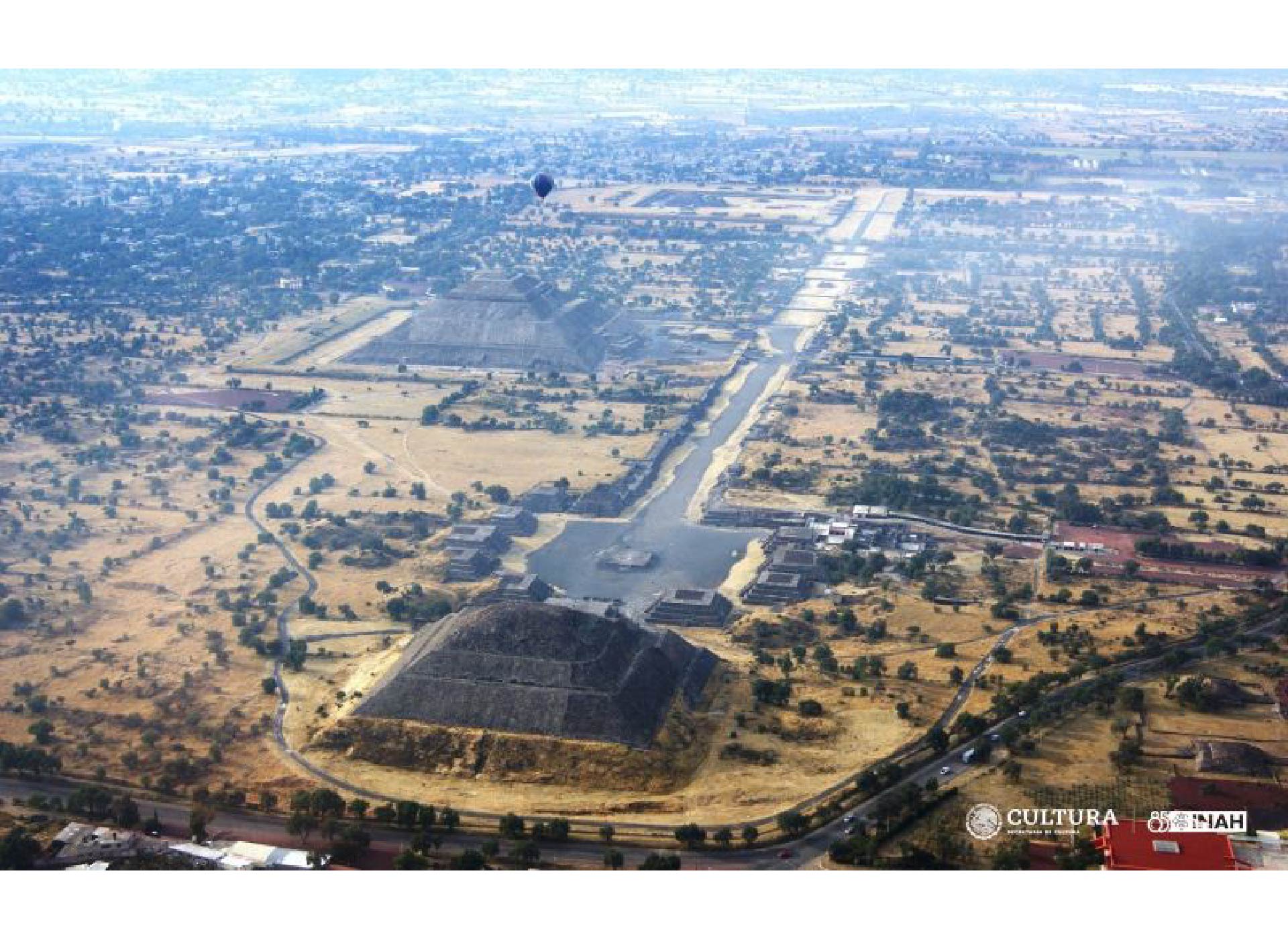

Teotihuacán flourished between roughly 100 B.C. to A.D. 800 and had a population of around 100,000 people. The "Pyramid of the Moon" was built in stages between roughly A.D. 1 and 350 and is located at the end of the "Causeway of the Dead," a long street that runs through the center of the city.

The team took a large number of measurements, including information from drone flights, to reveal that the northeast corner of the Pyramid of the Moon aligns with the sun when it rises over the El Xihuingo volcano on the summer solstice, which occurs between June 20 and 21 each year in the Northern Hemisphere, Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) said in a Spanish-language statement. The researchers also found that the southwest corner of the pyramid aligns with the sun as it sets behind a hill during the winter solstice, which occurs between Dec. 21 and 22 each year.

The summer-solstice alignment involving the volcano is particularly interesting, the team said, as there is evidence that the people of Teotihuacán used the volcano as an astronomical observatory of sorts.

"On the slopes of the El Xihuingo volcano is the Xihuingo archaeological site, a place where petroglyphs known as dotted crosses were created [and] whose function has been proposed as astronomical markers," Aarón González Benítez, an archaeoastronomer at the National School of Anthropology and History in Mexico and a member of the research team, told Live Science in an email.

The pyramid's alignment with the solstice sun appears to have affected the orientation of the entire city. "The city of Teotihuacan stands out among other things for its magnificent reticular design, and if the solar orientations of the Pyramid of the Moon determined the orientation of the city, the other monuments that are parallel to this great building would be following and replicating the same canonical orientation," González Benítez said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sun or moon?

It may sound strange that a structure called the "Pyramid of the Moon" would instead follow the solstice sun. But González Benítez noted that the name was given by the Mexica people, who founded the Aztec Empire, and they didn't name the pyramid until sometime after the city was abandoned. We don't actually know what the inhabitants of Teotihuacán would have called the structure, he said.

Interestingly, there is another pyramid at Teotihuacán called the "Pyramid of the Sun," but the team's research suggests that the northeast and southwest corners of that pyramid actually align with the "lunistices" (also known as lunar standstills), a time when the moon appears at its highest or lowest points in the sky.

Some of the team's results also turned up in previous research, Steven Gullberg, a professor of cultural astronomy at the University of Oklahoma, told Live Science. "I don't disagree with the orientations that they found, and this will make for an interesting debate among those who specialize in the astronomy of this area. I look forward to seeing their opinions."

Ivan Sprajc, head of the Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies at the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, said it is difficult to believe that the city was built with a solstice alignment involving the Pyramid of the Moon in mind. He noted that the Pyramid of the Moon was modified during its construction and its earliest phase had a different orientation than it does today.

The team, which includes project coordinator and principal researcher Ismael Arturo Montero García, is writing a book that will include the results of their research. Additionally, they have released a documentary on their findings.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.