Viking Age women with cone-shaped skulls likely learned head-binding practice from far-flung region

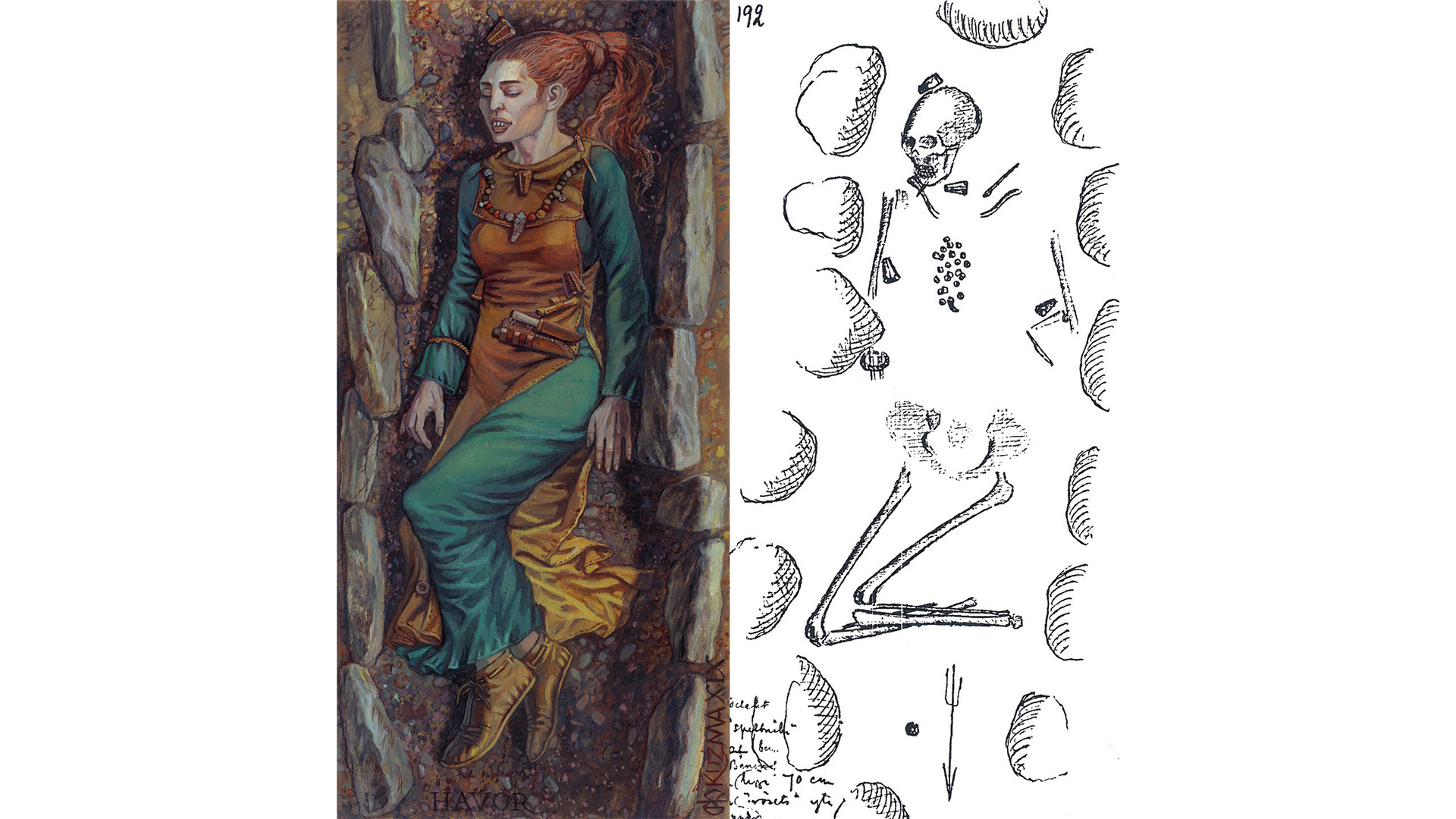

The skull modifications were found on the skeletons of three women buried on Gotland almost 1,000 years ago.

The elongated, cone-shaped skulls of Viking Age women buried on the Baltic island of Gotland may be evidence of trading contacts with the Black Sea region, a new study finds.

The women's skulls were most likely modified deliberately from birth by wrapping their heads with bandages. This practice is attributed to the nomadic Huns, who invaded Europe from Asia in the fourth and fifth centuries, and it was followed in parts of southeastern Europe until the 10th century.

But the modifications have been found only on the skulls of three Viking Age (A.D. 793 to 1066) women buried on the now-Swedish island of Gotland and nowhere else in Scandinavia, which indicates it was a foreign practice, said study lead author Matthias Toplak, an archaeologist at the Viking Museum Haithabu in Germany.

While it's unclear if the skull modifications were disguised by a distinctive hairstyle, "I assume that the foreign (or rather alien) appearance of these females was visible," Toplak told Live Science in an email. "It might have been a token of a certain elite or some other social group."

It's likely the modified skulls were restricted to a few women from one family across a few generations, perhaps to highlight their connection with a distant region where the modifications were more common, he said; at least one of the women may have originated in that region.

"I suggest that the skull deformations on Gotland were regarded as evidence of far-reaching trading contacts, and thus as tokens of influence and success in trading," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Filing down teeth

In the study, published Feb. 24 in the journal Current Swedish Archaeology, Toplak and his co-author Lukas Kerk, an archaeologist at the University of Münster in Germany, looked at the evidence of skull modification from Gotland and filed teeth found on skulls around Scandinavia.

The authors suggest the practice of filing teeth may have been used as a sign of identification — perhaps clandestine — for certain groups of Viking Age merchants and may have been conducted as an initiation rite.

Previous research has proposed that the marks may have resulted from teeth used as tools — while leatherworking, for example.

But the new study shows the marks were made deliberately. "The filings observed in Viking Age Scandinavia must be intentional," Toplak said. "Modern experiments indicate that an iron file is necessary to achieve these distinct grooves."

The practice seems to have originated in Sweden's Uppland region, but the latest study suggests a concentration of filed teeth in skulls buried on Gotland show the island's importance for trade. "Gotland is the central hub for all trading activities in the Baltic from the later Viking Age, on through the entire Middle Ages," he said.

But tooth filing seems to have died out in Scandinavia after the 12th century. "The decline of this custom corresponds with the development of the classical merchant guilds in the Middle Ages," Toplak said.

Viking body mods

The study attempts to explain the filed teeth and the cone-shaped skulls from Viking Age Gotland by placing them in the cultural context of the time.

The Viking Age Scandinavians were famous for their tattoos, which were described in a 10th-century travelogue written by the Arab diplomat Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān. But until now, there had been little discussion of other forms of Viking Age body modifications, the authors wrote.

Kurt Alt, an archaeologist at Danube Private University in Austria who wasn't involved in the study, said such artificially modified skulls were found in numerous contexts throughout the world and usually among women. Such skulls were not always signs of foreign-born women, because some native-born women also imitated the custom, he said.

"The skull, face and teeth are particularly well suited to reflecting an identity," Alt said. "Other parts of the body are not visible enough."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.