Viking market may be buried on a Norwegian island, radar suggests

The Norwegian island of Klosterøy is famous for its medieval monastery, but new research suggests it was important long before that.

A Viking Age marketplace may be buried on a Norwegian island, new research suggests.

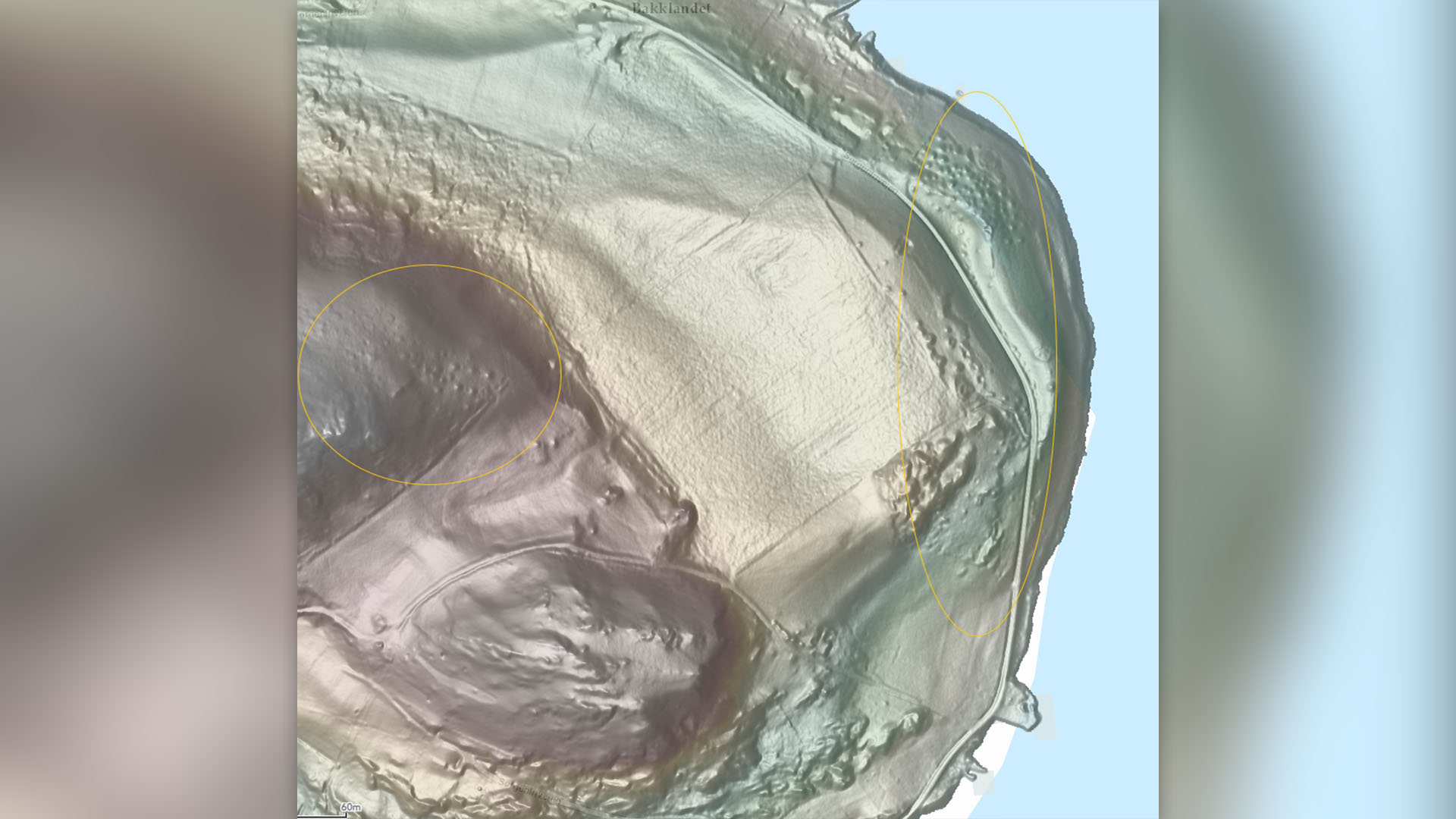

Archaeologists surveying part of the historic island of Klosterøy, in southwest Norway about 190 miles (300 kilometers) west of Oslo, used ground-penetrating radar to detect signals from what appear to be the buried remains of several pit houses and piers.

The archaeological remains suggest the site could have been a market during the Viking Age (A.D. 793 to 1066), and other finds hint that the place was important to local people long before that, according to Kristoffer Hillesland, a researcher at the University of Stavanger's Museum of Archaeology who took part in the research.

"It was likely that this was a power center during the Iron Age," or from about 500 B.C. to A.D. 800 in this region, Hillesland told Live Science, noting that several large burial mounds from this period are visible nearby.

The marketplace would have been established later, he said, possibly when the island was a royal farm for the first king of Norway, Harald Fairhair (reigned A.D. 872 to 930), and a monastery for Augustinian monks was built beside the site in the Middle Ages.

The monastery, too, could be a sign that a settlement on the island was a local center of power, because early Christian institutions in Scandinavia tended to be built at such places, he said.

Related: What's the farthest place the Vikings reached?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Klosterøy is also only a few miles from the island of Karmøy, where three Viking ship burials have been found.

The monastery, now known as Utstein Abbey, was abandoned in the 16th century during Norway's Protestant Reformation, but the building was later used as a farmhouse. It is now legally protected as Norway's best-preserved medieval monastery.

Buried ruins

The latest study surveyed the land beside the monastery, Hillesland said, where numerous metal detector finds of items like coins and weights over several years indicated that commercial trade had taken place there.

Archaeologists conducted the new research without excavating the land at the site, which is within the legally protected historic area. Instead, they used ground-penetrating radar to reveal what was buried there.

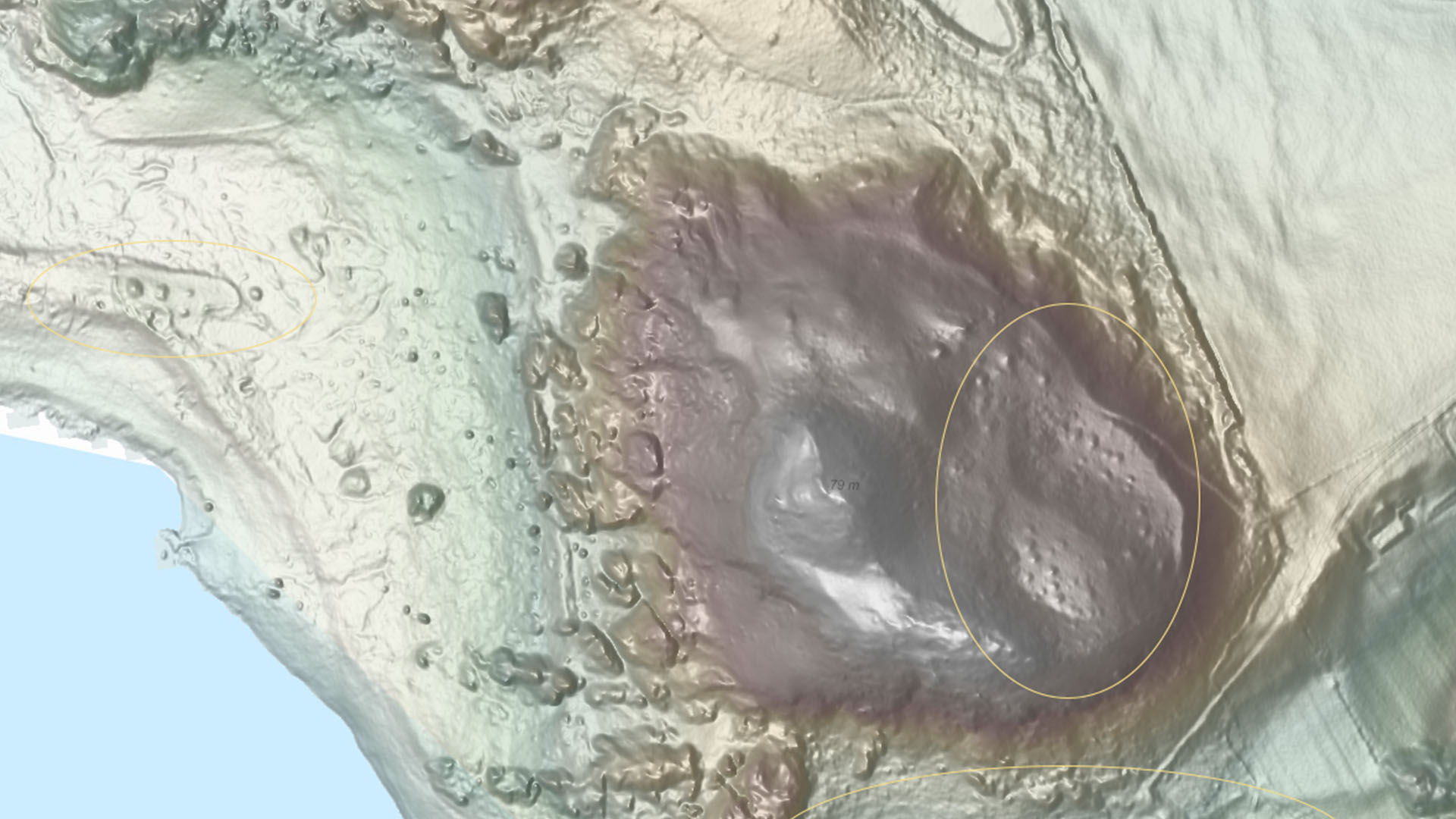

Hillesland explained that the team had detected buried traces of several circular pits, measuring between 6.5 and 33 feet (2 and 10 meters) in diameter, that were very similar to Viking Age "pit houses" excavated at other sites in Norway.

Pit houses were used in many places in Europe and were particularly common in Scandinavia until the Middle Ages. They were dug so the floor was below ground level and then covered with an angled roof typically made from wood, turf or thatch; the design helped the buildings stay cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

The remains of such pit houses have often been found at Iron Age and Viking Age marketplaces in Scandinavia, where they seem to have been used as workshops for activities such as weaving, Hillesland said.

The survey also revealed the buried remains of three piers or boathouses near the shore, which may have been where boats docked to access the market, the royal farm or perhaps the later monastery, he said. It's possible that the market operated there only during the warmer months, and people may have visited the market by boat from other islands or the mainland when it was open.

Taken together, the evidence of the survey and the metal detector finds suggest that a marketplace existed at the site during the Viking Age and early Middle Ages, Hillesland said.

Ancient cairns

Other archaeological features of the island suggest it was an important site for some of the earliest people in the region. Piles of rock called "cairns" have been found near the monastery; these may be signs of Iron Age burials, and some of the nearby burial mounds may have been built even earlier, he said.

The ground-penetrating radar had also shown what may be the remains of cooking pits, which seem to have been related to funeral activities around the older burial mounds at the site, Hillesland said.

He stressed that the remains of a Viking Age marketplace at the site couldn't be confirmed until it had been fully excavated. But the site and the monastery are on private land, and no such excavations have been planned, he said. Nonetheless, the ground-penetrating radar signals provide a hint of what future archaeologists may find.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.