Was Alexander the Great eaten by sharks? Inside the wild theories for what happened to the iconic ruler's body.

The remains of Alexander the Great may lie under the streets of Alexandria, they may have been "eaten by a shark," or they may be somewhere else entirely. But one thing is certain: Archaeologists don't agree.

When Alexander the Great died in 323 B.C., 13 years after building one of the world's largest empires, he left what would become one of the biggest unsolved mysteries in archaeology.

Researchers have hotly debated where Alexander the Great is buried, with theories ranging from his homeland in Macedonia (now Greece) to Egypt.

Like the Holy Grail or the Ark of the Covenant, the tomb has taken on a mythical status that has captivated many archaeologists over the years.

"As long as his tomb isn't found, he lives on in a quasi-mystical limbo, forever sparking new ideas and theories and controversies," Nicholas Saunders, a professor emeritus in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom and author of the book "The Life of Alexander the Great" (Brighter Child, 2006), told Live Science in an email.

Hundreds have hunted for the tomb, to no avail.

"I remember in 1963 when I was a student at Alexandria University, there was a Greek man who was doing excavations near the [train] station," Zahi Hawass, an archaeologist, Egyptologist and Egypt's former minister of antiquities, told Live Science. "I used to go and see his excavations. He found nothing, but he stayed five years, searching."

But have archaeologists made any progress on finding the tomb? Calliope Limneos-Papakosta, director and founder of the Hellenic Research Institute of Alexandrian Civilization, who is currently excavating in Alexandria, Egypt, thinks she's close.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

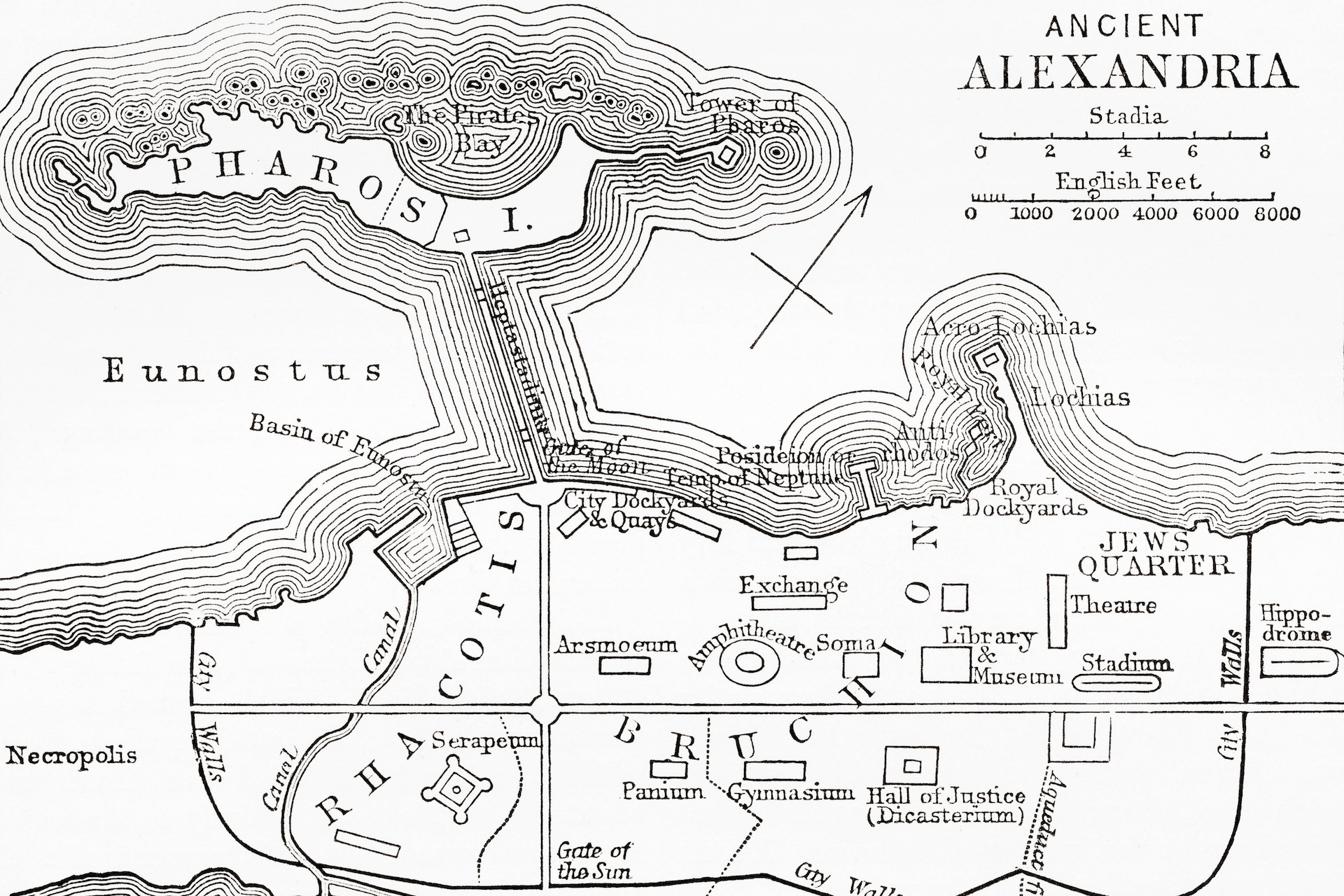

The tomb may be hidden beneath the streets of modern-day Alexandria, at the intersection of two ancient thoroughfares, she said. An intriguing Hellenistic statue and other signs of ancient quarters from the right period point to a very promising location.

"I am at the crossroads, and I believe that I have more possibilities to find the tomb than anybody else," Limneos-Papakosta told Live Science.

Why finding the tomb is so difficult

One reason the tomb still hasn't been found is because Alexander's body was moved, and so he was buried more than once.

In addition, historical records of the tomb are scarce and were often written hundreds of years after the events they describe. Each of those sources had a political agenda or bias, said Paul Cartledge, a professor emeritus of Greek culture at the University of Cambridge.

"So, you have to take everything with a large pinch of salt," Cartledge, author of "Alexander the Great" (Overlook Press, 2004), told Live Science.

Compounding the difficulty is that there are no clear images of the tomb that could guide archaeological searches, Saunders added.

Finally, the modern city of Alexandria was largely built over the original.

"Modern Alexandria, especially the downtown area, was built completely above ancient monuments," Hawass said. "The theater was found while they were building houses. And catacombs were also found."

To find the tomb, archaeologists would have to dig up places where people live and work today, which is challenging without strong evidence that something important lies beneath.

What we know about Alexander's death and burial

We know from historians like Plutarch that, at age 32, Alexander died sometime between the evening of June 10 and the morning of June 11, 323 B.C., in Babylon (modern-day Iraq). His cause of death is controversial, with some proposing he died of diseases such as typhus or malaria or from drinking poisoned wine, and others arguing he was assassinated. (A few people even think he was declared dead prematurely.)

Related: How did Alexander the Great die?

Regardless of what killed Alexander, his body was mummified. Ptolemy I Soter, a Macedonian Greek general who was Alexander's close friend and bodyguard, was instrumental in moving the body.

"His corpse was taken en route via the Middle East through what is now Iraq to what's now Syria," Cartledge said. From there, over two years, it would travel almost 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) to Egypt.

Ptolemy had an agenda: Alexander had left no clear political heir (although his wife Roxana was pregnant with his son and he may have had an illegitimate heir), and building a tomb for Alexander was a way to cement Ptolemy's position as the legitimate successor to the Macedonian king, Cartledge said.

Alexander's body was then shipped to the Valley of the Kings near Luxor, Egypt, where many of the New Kingdom pharaohs were buried, while the newly founded city of Alexandria was being built.

"In 305 B.C., 18 years after he died, Alexander's corpse was brought to Alexandria, by which time there's a royal court, a palace and a museum," Cartledge said. "Having Alexander buried there would have been the icing on the cake" for the nascent city.

A few decades later, accounts by Greek geographer Strabo suggest Ptolemy IV Philopator, the fourth pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt and the great-grandson of Ptolemy I, moved Alexander's body to its final documented resting place: Soma, Alexandria's great mausoleum, according to the book "Alexander's Tomb: The Two Thousand Year Obsession to Find the Lost Conqueror" (Basic Books, 2006).

Related: 2nd-century Alexander the Great statue with lion's-mane hairstyle unearthed in Turkey

It was still there around 300 years later, when the first Roman emperor, Augustus (reigned 27 B.C. to A.D. 14), visited Alexandria.

"He was desperate to view the corpse of Alexander," Cartledge said. "Apparently it was so visible that when he bent down, he knocked the corpse's nose off."

After that, the historical record makes no reference to the tomb for hundreds of years. "It disappears from mention around A.D. 500," Cartledge said.

Big gaps in the timeline

What happened to the tomb during the large gaps in the historical record has been a source of fevered speculation and even outright conspiracy theories ever since. These time spans also make it difficult to focus on specific theories about the tomb's current location.

Saunders thinks these interludes in the timeline are strange.

"It was only some 300 years after Alexander's death that we get an account [of the tomb]," while most records come from 600 years later, Saunders told Live Science in an email. "So, what happened in the intervening period? Why the silence?"

For hundreds of years, the tomb was a "very well-known pilgrimage center across the ancient Mediterranean world," he added, so at the time, the "location was not a secret."

So it's possible that no one bothered to describe the tomb's location because everyone knew where it was. There also may have been a rivalry between Christians flocking to Christ's tomb and pagans worshipping at Alexander's tomb. So once Christianity had the upper hand, Church fathers may have "made sure traces of the tomb were removed/damaged/destroyed so that Christ's tomb could then become the preeminent pilgrimage center of the ancient world," Saunders said.

"Alexander is buried in Alexandria, and we are sure about that because in the first century A.D., we have information about visitors to the tomb, including Roman emperors like Julius Caesar."

Calliope Limneos-Papakosta

Limneos-Papakosta thinks the site's location may have been lost during the Alexandrian Crusade in 1365, which ransacked the city, though no historical records suggest the tomb or actual body was destroyed, she said. However, one possibility is tied to the worship cult that arose around Alexander the Great. While it ostensibly died out thousands of years ago, there may have been people left in Alexandria who, during the crusade, still felt called to protect Alexander's remains from the incoming crusaders, who would have despised the worship of pagan gods.

"I believe that the priesthood around the cult of Alexander protected the tomb," Limneos-Papakosta said. "He was considered a god, and they tried to protect him when they realized that destruction was coming by Christians. I believe that they hid his body and sarcophagus."

Because Alexander's last known resting place was in Alexandria, most researchers agree that his tomb is likely hidden somewhere in the Egyptian city.

"Alexander is buried in Alexandria, and we are sure about that because in the first century A.D., we have information about visitors to the tomb, including Roman emperors like Julius Caesar," Limneos-Papakosta told Live Science. "So, we know that the tomb was there."

But exactly where in Alexandria is the question.

Shallalat Gardens

Limneos-Papakosta has one theory. During a 2009 excavation, she discovered a sculpture of Alexander, according to an article she wrote for Newsweek.

"It was our last day at the site, and we were ready to end the season," she said. "But then we found the sculpture. It was kind of a miracle."

Topographical maps and ancient sources suggest the area where the statue was found is close to where his tomb was once located, Limneos-Papakosta said, and her team has been excavating in the area ever since. Now, she thinks she's getting close, narrowing it down to the Shallalat Garden area of modern-day Alexandria, located near the Alexandria National Museum, which contains the remnants of the city's walls. Ancient sources suggest the royal quarters were in this location during antiquity, she said, yet they had never been excavated, she said.

The dig site is next to a former ancient intersection mentioned by second-century Greek writer Achilles Tatius, who describes the tomb's location.

"He wrote that it was a few hundred meters west of the intersection of Alexandria's two main broad streets," she said. Thanks to the current excavations, "we already knew of one of the broad streets [known as Canopic Street], but now we know of the second, Royal Street."

Under the sea

But others think Limneos-Papakosta is on the wrong track.

Cartledge, for his part, speculates that the body must have been housed inside a large mausoleum that was part of a royal complex. And he thinks the royal quarters were located in a different location than Papakosta-Limneos does.

"A mausoleum conveys the notion that it's a very solid structure that should be locatable," Cartledge said. "The one in Rome, Augustus' mausoleum, is completely visible. Why isn't the mausoleum of Alexander visible? The simple answer is that the Brucheum of Alexandria, where the royal quarters were, abutted the sea," Cartledge said. (The Brucheum was a particular quarter of Alexandria.)

But sea levels have risen several meters since the time of Alexander, historical maps suggest, so large swaths of the historical city, including the royal quarters, probably sit underwater.

In recent years, divers have explored the city's coastline and found pieces that could belong to ancient structures.

But even if a mausoleum is found, there's no guarantee a body would be inside. "Unless he was in a coffin that preserved his body, he will never be found," Cartledge said. "My guess is that his body could've been eaten by a shark."

Mazarita district

Saunders thinks the tomb is still on dry land, likely beneath the bustling streets of the modern Mazarita district, an area that was once the ancient city's hub and housed its palaces.

"Unless and until new building projects require demolition and clearance to a deep level, it is unlikely to be discovered," Saunders said. "For me, it is all but inconceivable it could be anywhere else."

Hawass doesn't have one site in mind, but he's optimistic that the tomb will be found one day.

"Can we say that the tomb can be discovered?" Hawass said. "Yes."

But it probably won't be found by archaeologists who are searching for it. The theater, catacombs and many of ancient Alexandria's monuments were found by accident, thanks to modern construction.

"The tomb will never be discovered by scholars — at all," Hawass said. "I really believe that by accident one day, the tomb of Alexander the Great will be discovered."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.