What's the oldest known case of cancer in humans?

The first known case of cancer was discovered in an early human relative's toe bone.

Cancer may seem like a modern disease, but it has affected humans for eons. Scientists have discovered numerous prehistoric human remains indicating the presence of cancer. So, what's the earliest case of cancer on record? And what's the first time that humans wrote about it in medical texts?

The earliest evidence of human cancer comes from an early human relative who lived around 1.7 million years ago. This individual, likely of the species Paranthropus robustus or Homo ergaster, lived with a malignant tumor in their left toe bone. Archaeologists discovered the skeletal remains inside Swartkrans cave, a limestone deposit in South Africa that's often called the Cradle of Humankind for being home to the largest concentration of human relative remains in the world.

When researchers compared computed tomography (CT) scans of the toe bone fossil with images of modern-day cases of osteosarcoma, an aggressive form of cancer that begins in the cells that form bones, they immediately recognized the distinctive cauliflower-like appearance of an osteosarcoma, according to a 2016 study about the case published in the South African Journal of Science.

Nowadays, osteosarcoma is one of the most common bone cancers in humans and can occur at any age, although it is most frequently seen in children, teenagers and young adults who are still growing, according to the American Cancer Society. However, while this prehistoric individual's age is unknown, it appears that they were an adult, the researchers said.

Related: If blood is red, why do veins look blueish?

An even older benign tumor was found in a 1.9 million-year-old human relative known as Australopithecus sediba found in South Africa, according to a separate 2016 study in the South African Journal of Science.

It's not surprising that the oldest known cancer case was in a bone, since organs, skin and other soft tissues are more prone to decay than bones are.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Bone is one of the few tissues that can survive in the fossil record," Bruce Rothschild, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

However, even if cancer is present in a fossil, it often isn't visible to the naked eye and takes further examination to find — which was the case for the toe bone.

"About one-third of cancers will show themselves," Rothschild said. "But you would need to perform an X-ray to determine if something was hidden inside the bone. Most pathologists [today] look at an X-ray before coming up with a diagnosis of a tumor when it involves the bone."

First written record of cancer

Although the 1.7-million-year-old toe bone is the earliest known case of cancer in a hominin, a group that includes modern humans, the first written record of cancer doesn't show up until much, much later.

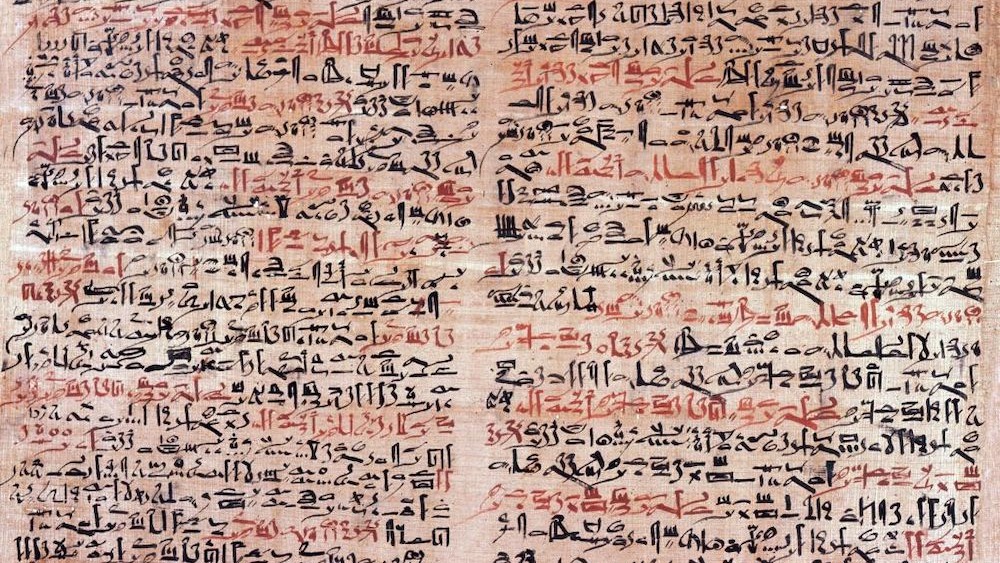

In 3000 B.C. Imhotep — an ancient Egyptian mathematician, physician and architect — wrote what came to be known as the Edwin Smith Papyrus, a textbook about bodily trauma and surgical procedures. In the text, he detailed 48 medical cases, including several case studies on breast cancer.

The text was written in hieratic, an ancient Egyptian writing system, and was later translated into a two-volume English text by American archaeologist James Henry Breasted. In it, Imhotep described characteristics of different types of tumors, including "oily tumors" and "solid tumors." He also included descriptions of a breast tumor — describing it as "bulging mass in the breast" that is cool, hard and as dense as an "unripe hemat fruit" that spreads under the skin, according to the book "The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer" (Scribner, 2010).

While Imhotep gives a number of treatments for the other medical conditions in the text, under "therapy" for the breast tumor he wrote, "There is none." However, he did note the best practices for binding other types of tumors, which involved creating an ointment made of grease, honey and lint, according to The Cancer Letter, which published an excerpt of the historical text.

The papyrus not only offers a glimpse of how surgical medicine was practiced thousands of years ago by ancient Egyptians, arguably some of the world's first surgeons, but also provides some of the earliest evidence of cancer ever recorded, according to a 2016 study published in the journal Cancer.

It's unclear how these cases of prehistoric cancer developed. Just like the humans who came before us, we're still trying to figure out what causes many cancers and the best ways to treat them.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.