Wreckage from Tuskegee airman's warplane recovered from Lake Huron

The recovered wreck will help tell the full story of America's first Black military pilots.

Divers have recovered the engine of a World War II fighter from the cold waters of Lake Huron off the coast of Michigan, where the airplane crashed almost 80 years ago during a training flight.

The crash claimed the life of the plane's pilot, 22-year-old 2nd Lt. Frank Moody, who was one of the many "Tuskegee Airmen" assigned to an army air base southwest of the lake to train on advanced aircraft.

The Tuskegee Airmen — also known as "Red Tails" from the colors painted on their aircraft — included the first Black military pilots in the United States, as well as Black navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, medics and cooks; but racial segregation in the U.S. military meant they trained and operated separately.

More than 320 Black pilots trained at air bases near Tuskegee in Alabama flew in fighters and bombers over Europe, and 66 were killed in combat.

Wayne Lusardi, the state maritime archaeologist for Michigan, told Live Science that many of the Tuskegee pilots were sent to Selfridge Field, an air base outside Detroit, for advanced training after getting their wings.

Related: 30 incredible sunken wrecks from WWI and WWII

It was during one of these training flights, on April 11, 1944, that Moody's P-39 Airacobra crashed at high speed into Lake Huron, apparently because the guns on the warplane critically damaged its propeller.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Warplane wreck

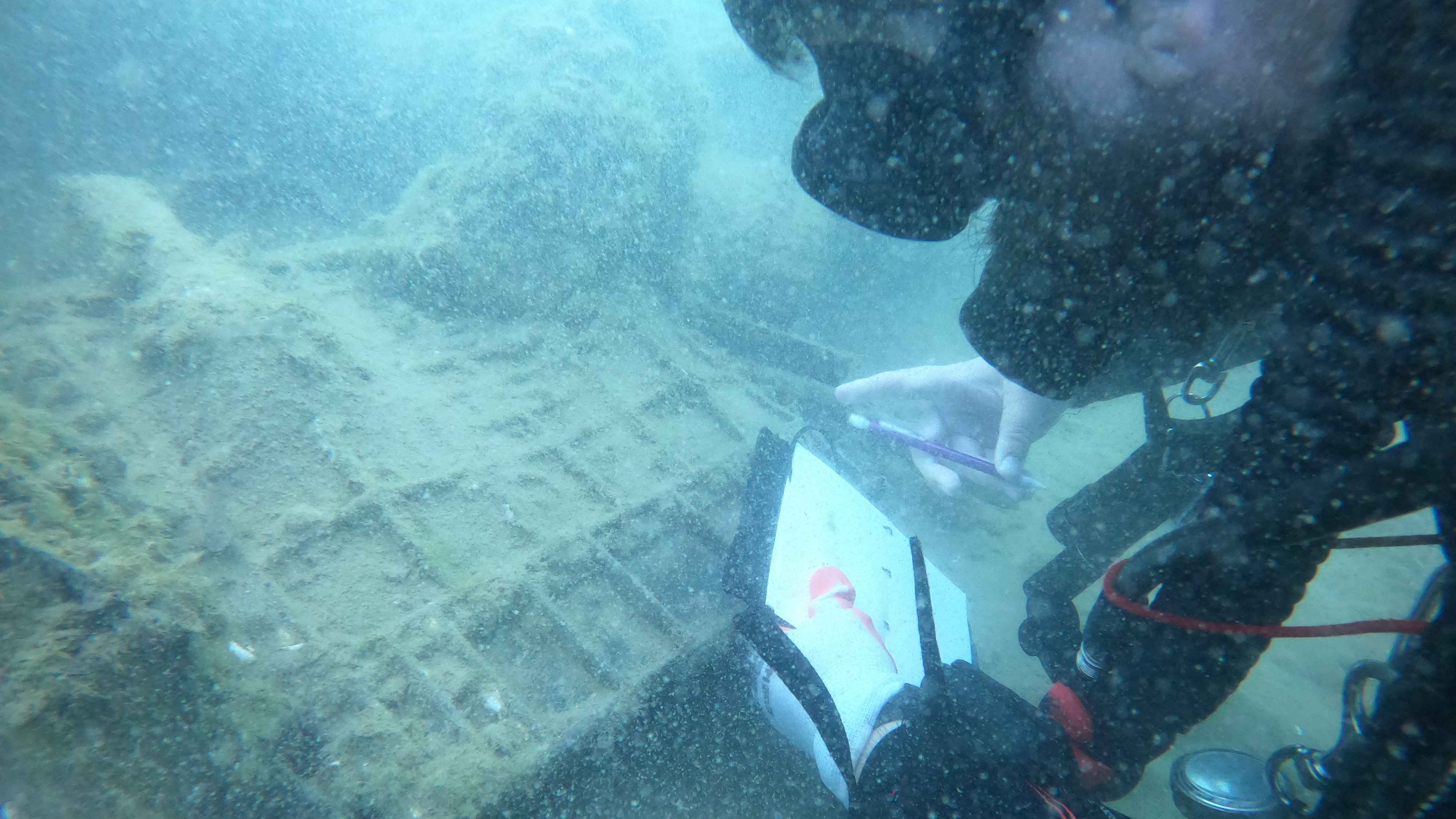

Lusardi has led several recovery dives to the wrecked aircraft since it was discovered in 2014 by divers salvaging a barge that had sunk in the same area.

"They came across what looked like a car door, and wondered why there was a car door on the lake floor," he said. "And it turned out that it was from a P-39."

Moody was flying at more than 200 miles an hour (320 km/h) when his Airacobra crashed into the lake, and the wreckage is now spread out over a wide area, about 1 mile (0.6 kilometers) offshore in the southern part of the lake and beneath about 32 feet (10 meters) of water.

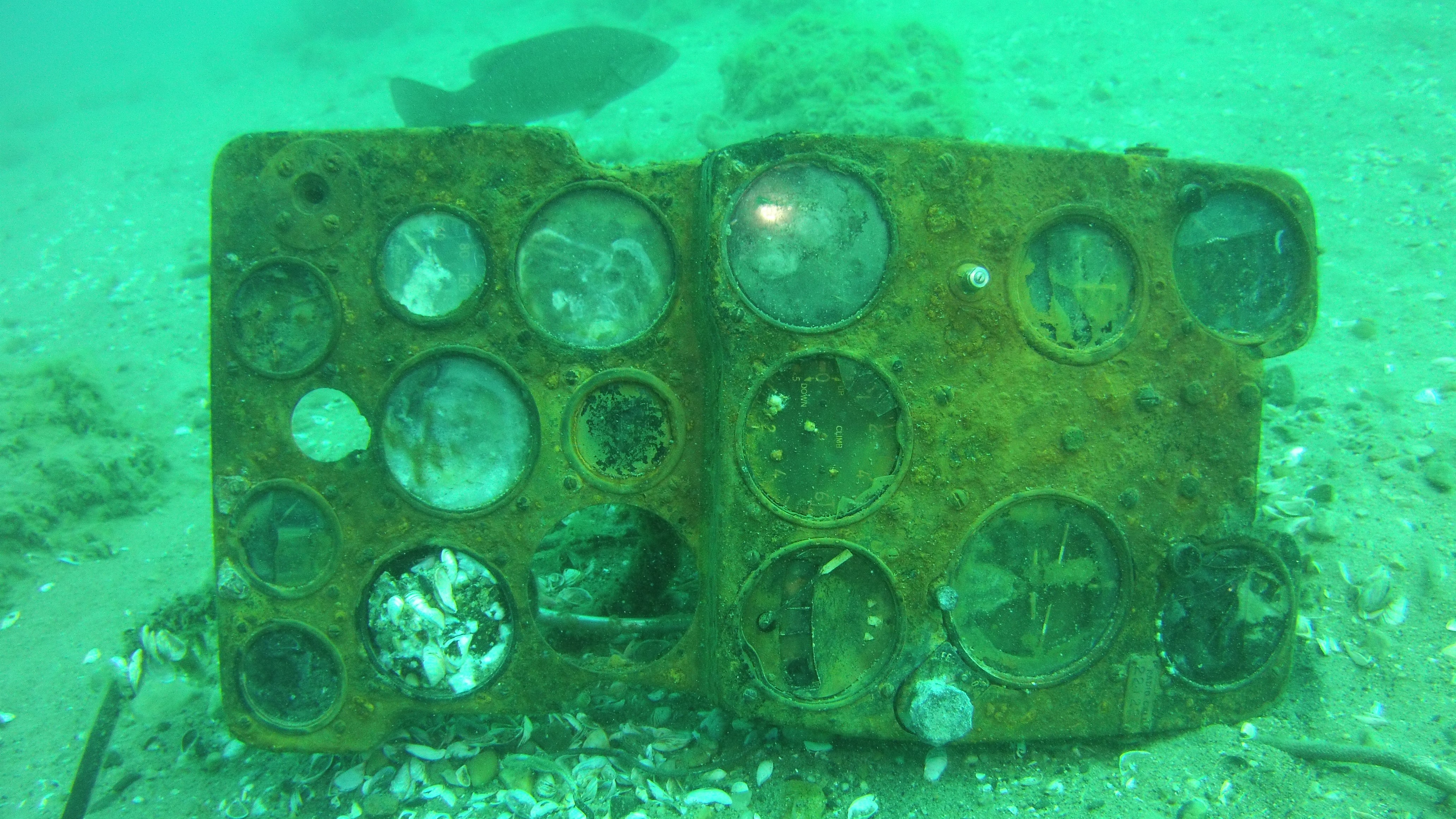

Divers have recovered several pieces of the fuselage and other parts, including a distinctive instrument panel with serial numbers that were used to identify the aircraft, he said.

They've also recovered the propeller, which shows clearly where it was struck by the warplane's own bullets. The guns were supposed to be synchronized so the bullets wouldn't hit the propeller, but instead they caused the fatal crash.

"For whatever reason the guns went out of sync, and so when the pilot pulled the trigger, the bullets ripped off one propeller blade and damaged another," Lusardi said. "And he was only about 50 feet [15 m] above the lake, so it was all over."

Sunken engine

The latest dives this summer recovered the warplane's engine, an almost solid block of metal that weighs more than 1,200 pounds (545 kilograms).

Lusardi said the next large piece of the wreck for recovery is its 32-foot-long (10 m) pair of wings, which separated from the fuselage during the crash but are still together.

When enough of the warplane is recovered and restored, it will go on display at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum in Detroit, which is planning a new building to house it.

Moody's P-39 will help tell the full story of the Black American pilots and other airmen who helped fight the war, according to Brian R. Smith, the museum's president.

"Tuskegee Airmen are known for their valor and excellence in fighting the Germans in the air war over Germany in World War II," he told the Associated Press. "But what we haven't heard about is the accidents in training that the airmen suffered."

Lusardi, meanwhile, is investigating the wrecks of at least three more warplanes from Selfridge Field still submerged in Lake Huron.

"Most airplane accidents happen near airports, and a lot of the wreckage is cleaned up entirely," he said. "But planes that go missing out at sea or in a lake could have archaeological potential."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.