Are rainbows really arches?

If you have the right vantage point, a rainbow might look circular. Here's the science behind why some rainbows look like arches and others don't.

Rainbows are colorful arches that stretch high into the sky, and they end somewhere in the distance (where the fabled pot of gold can be found), right?

Wrong.

Rainbows are actually not arches. They form as full circles when sunlight passes through raindrops at just the right angle. However, only part of the circle — the arch — is visible to the observer on the ground. Earth's surface blocks the rest of the light — and, therefore, the rest of the halo — which is why it appears as a rainbow.

How much of the halo is visible depends on where the observer is standing and how much of the surface is in the way, said Michael Kavulich, a research scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, and an expert on rainbows and why we see them as we do. It depends on refraction — how light is bent when it hits a raindrop — and reflection, which is light bouncing back. To understand why rainbows are really halos, you need to know how they form.

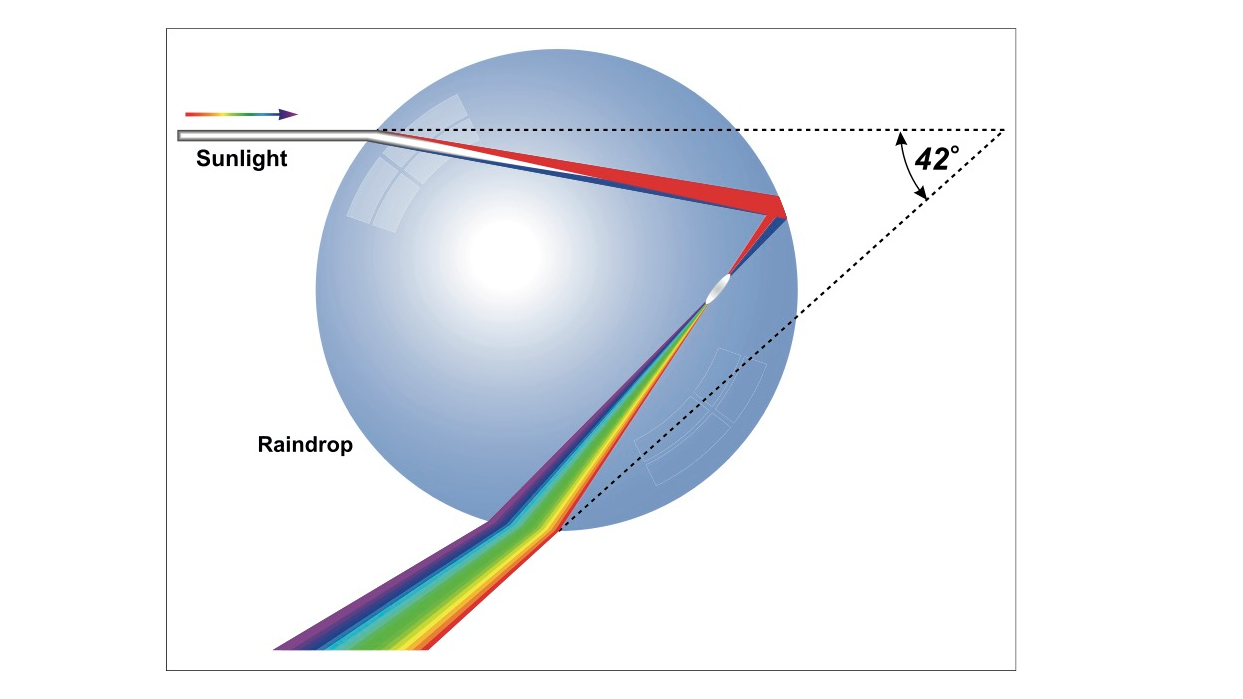

"Most light entering a spherical raindrop ends up getting refracted at nearly the same angle, and if it also reflects once off the back of the raindrop this angle ends up being around 40-42 degrees from the direction the light is coming from," Kavulich told Live Science in an email.

Related: Why does rain smell so good?

Yes, raindrops are actually spherical, not teardrop-shaped. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, light starts to bend, or refract, when it enters a raindrop because water is denser than air. The light continues to travel until it reaches the back of the raindrop. This is the phase where light bounces off the back. Now on its way out of the raindrop, the light refracts one more time and then separates into its iconic colors.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because raindrops are spherical, they reflect light in a cone shape. And what is at the end of the cone? That's right: a circle. So, while the pot of gold at the end of a rainbow may be a myth, a rainbow is still the end of something.

An observer's ability to see a rainbow depends on where they are standing in relation to the sun. What becomes visible is the light refracted and reflected at a certain angle — as Kavulich mentioned, about 40 degrees from that light's source — that hits the eye directly. For this to happen, the shadow of the observer's head has to be positioned exactly opposite from the sun (without the obstruction of clouds) so it can be in the middle of the circle, even if the entire circle is not visible. This is how they can see light refracted and reflected through the raindrops right in front of them.

"Because of this, if you move, the rainbow does too, always staying in the same spot in the sky relative to the sun," Kavulich said. "You can only see it change if you look over a long period of time, as the sun rises or sets across the sky."

So why do we see colors in the classic ROYGBIV order? It's all about wavelengths of light. Kavulich explained that because red light has the longest visible wavelength, it is refracted the least, so it ends up at the top. Violet is at the bottom because it has the shortest wavelengths, which are refracted the most.

So, given that rainbows aren't actually arches, is there any way to see an entire rainbow in circular form? An airplane window is probably your best bet, though all or most of the circle is often visible from skyscrapers. There is sometimes a clear view from other high elevations such as mountains. Even then, too much is usually in the way.

Rainbows are actually full circles, typically visible from higher vantage points, such as planes or tall buildings.Credit: Fabricio Macielpic.twitter.com/MBtgOD9C4cSeptember 12, 2022

If you have no luck from those locations, you can try Kavulich's method of creating a circular rainbow with a garden hose.

"You just need sunlight to be able to hit raindrops that you can see," he said. "With the right placement, I was able to see the whole circle at once."

Elizabeth Rayne is a contributing writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in SYFY WIRE, Forbidden Futures, Grunge and Den of Geek. She holds a bachelor of arts in English literature from Fairfield University in Connecticut and a master's degree in English writing from Fordham University, and most enjoys writing about space, along with biology, chemistry, physics, archaeology and paleontology.