Massive tentacled microbe may be direct ancestor of all complex life

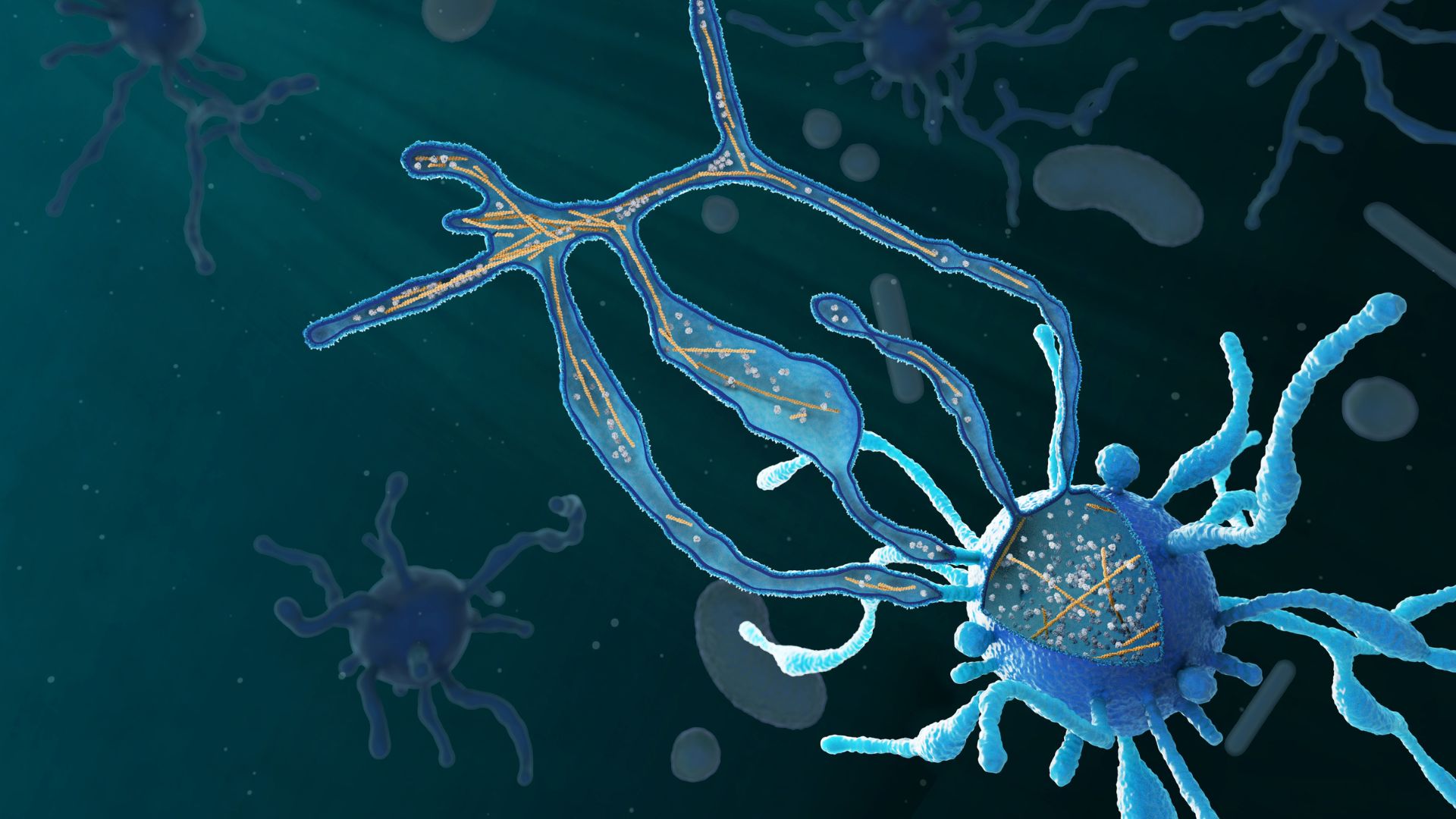

Scientists successfully grew Asgard archaea in the lab and took detailed images.

Ancient microbes whose existence predates the rise of nucleus-carrying cells on Earth may hold the secrets to how such complex cells first came to be. Now, for the first time, scientists have grown a large enough quantity of these microbes in the lab to study their internal structure in detail, Science reported.

Researchers grew an organism called Lokiarchaeum ossiferum, which belongs to a group of microbes known as Asgard archaea, according to a new report, published Wednesday (Dec. 21) in the journal Nature. Named after the abode of the gods in Norse mythology, Asgard archaea are thought by some scientists to be the closest evolutionary relatives of eukaryotes, cells that package their DNA in a protective bubble called a nucleus.

On the evolutionary tree of life, Asgards often appear as a "sister" of eukaryotes or as their direct ancestor, Jan Löwe, leader of the Bacterial Cytoskeleton and other Molecular Machines research group at the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology in the U.K., wrote in a commentary about the new study. Asgards don't carry nuclei themselves, but they do contain a suite of genes and proteins that were once thought to be unique to eukaryotes. Researchers have a variety of theories as to how Asgards may have gained primitive nuclei and thus birthed the first complex cells, which later gave rise to plants, animals and humans.

In 2020, a research group in Japan reported that, after 12 years of work, they'd successfully grown Asgards in the lab. They'd grown Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum, an Asgard named for the Greek god Prometheus, but details of the organism's internal structure remained elusive, Löwe said. Now, a different research group has grown and taken snapshots of the innards of L. ossiferum.

Related: Newfound viruses named for Norse gods could have fueled the rise of complex life

"The images are stunning," Buzz Baum, an evolutionary cell biologist at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology who was not involved in the work, told Science.

"It has taken six long years to obtain a stable and highly enriched culture, but now we can use this experience to perform many biochemical studies and to cultivate other Asgard archaea as well," co-senior author Christa Schleper, leader of the archaea ecology and evolution lab at the University of Vienna, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Compared with other Asgards, L. ossiferum grows relatively fast, doubling its number of cells in seven to 14 days, Löwe noted. In comparison, P. syntrophicum replicates every 14 to 25 days. Note that the familiar bacterium Escherichia coli replicates every 20 minutes or so. (The slow growth of these archaea is one factor that makes them incredibly difficult to culture.)

Gathered from mud in a canal on the coast of Piran, Slovenia, the L. ossiferum specimens have funky tentacles that extend from the body of each cell; odd bumps and bulges appear along the length of each appendage. These "surface protrusions" may support the idea that, at some point in evolutionary history, an Asgard grabbed a passing bacterium using similar extensions of its membrane and sucked the bacterium into its cell body, and this led to the development of the nucleus, Löwe wrote. The protrusions support the idea that such an interaction could have occurred, he explained.

L. ossiferum also carries tiny, lollipop-like structures on its surface, which "look like they come from another planet," Thijs Ettema, an environmental microbiologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands who wasn't involved in the work, told Science. The microbe also contains structural filaments that closely resemble those seen in the cytoskeleton, or supporting scaffold, of eukaryotic cells, Löwe wrote.

Some scientists think the new study strengthens the hypothesis that Asgards are eukaryotes' direct ancestor, but not everyone is convinced. Read more in Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.